For a new Culture on the Edge series “You Are What You Read” we’re asking each member to answer a series of questions about books — either academic or non-academic — that have been important or influential on us.

3. Name one of your favorite books that’s not a theory book.

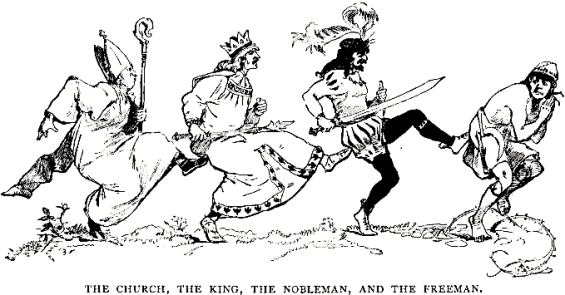

Naming two books is cheating I guess, but I adore Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. As Twain grew older — at least as I read him — he became almost as skeptical about morality as was Nietzsche. For Twain, humans are neither good nor evil; rather, human behavior simply follows from the processes socialization to which we’re subjected from the cradle, and moral evaluations of human behavior are not based on a universal ethics but are always relative to the sympathies with which one has been socialized. Consider the narrator’s commentary in Connecticut Yankee:

Naming two books is cheating I guess, but I adore Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. As Twain grew older — at least as I read him — he became almost as skeptical about morality as was Nietzsche. For Twain, humans are neither good nor evil; rather, human behavior simply follows from the processes socialization to which we’re subjected from the cradle, and moral evaluations of human behavior are not based on a universal ethics but are always relative to the sympathies with which one has been socialized. Consider the narrator’s commentary in Connecticut Yankee:

My land, the power of training! of influence! of education! It can bring a body up to believe anything. I had to put myself in Sandy’s place to realize that she was not a lunatic. Yes, and put her in mine, to demonstrate how easy it is to seem a lunatic to a person who has not been taught as you have been taught.

Whenever there was a dispute between a noble or gentleman and a person of lower degree, the king’s leanings and sympathies were for the former class always …. It was impossible that this should be otherwise.

Training is all there is to a person.

However, rather than throw up his hands in a nihilist, relativist defeat, he embarked upon a project of writing a series of works apparently designed to enlist the reader to his own sympathies. When Huck Finn considers his moral, Christian duty to turn in the runaway slave, Jim, he pauses to think:

[I] got to thinking over our trip down the river; and I see Jim before me, all the time, in the day, and in the night-time, sometimes moonlight, sometimes storms, and we a floating along, talking, and singing, and laughing. … [A]t last I struck the time I saved him by telling the men we had small-pox aboard, and he was so grateful, and said I was the best friend old Jim ever had in the world, and the only one he’s got now ….

After reflecting on his debt to Jim, Huck decides not to turn him in, and says “All right, then, I’ll go to hell.”

Here Twain doesn’t tell us what actions are good or evil; rather, he invites readers to put themselves in Huck’s place and to imaginatively participate in Huck’s sympathies — with the possibility that new sympathies might be habituated in the reader. Indeed, Twain is constantly encouraging readers to develop new sympathies and antipathies, even ones that might be at odds with readers’ prior “training.” In Twain’s work, moral denunciations of injustice and simplistic condemnations of others’ behavior are supplanted by the attempt to (re)socialize readers with new sympathies.

After Nietzsche, what other options are left to us?