If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you know that my children often figure significantly into my posts if only because people in the midst of being socialized are, in my opinion, some of the most interesting people around. This is also why so many of my posts about my kids are often focused on their educational experiences, for while there are a large number of ways in which we are socialized, most of these experiences are rarely as intentional and self-conscious as formal education. (If you’re interested, you can check out my reflections on their school introduction to Columbus Day and 9/11).

With that said, I recently had an interesting experience that shed some light on the ways that we negotiate our social rituals in order to suit the specific power relationships that such rituals foster. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day occurred a few weeks ago in the U.S., a holiday honoring the slain civil rights leader. Many of you, no doubt, saw all sorts of King-related posts on social media, most of them lines extracted from King’s larger speeches and writings, transformed into motivational statements like these:

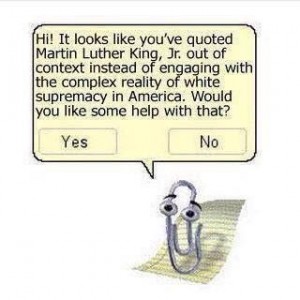

Others of us probably also saw posts published by another group of people attempting to draw attention to the fact that the original context in which the words of King-turned-meme were uttered were often highly controversial and divisive in their day, making their warm and fuzzy Facebook version a far cry from the circumstances that prompted those words in the first place:

So with that back and forth in mind, I was intrigued to find something at the bottom of one of my kids’ backpacks that put this tension on unusual display. Crumpled near the bottom layer of strata, I found a classroom assignment that included a drawing of two hands interlocked, one colored peach and the other colored brown. At the top of the page were words that were, no doubt, featured at the top of every child’s page: “My Dream” (obviously in reference to King’s “I Have a Dream” Speech). The assignment was for each child to provide three personal dreams. With that said, here were my kid’s dreams:

- That his parents would be unharmed (he’s a worrier, I should add);

- That it could be summer and snowy at the same time;

- That it would rain cats from the sky.

And finally, in messy pencil, scratched harriedly in the front corner, were the words “Cole is a butthead” (Cole is my second child and his older brother).

At first I had one of those parental “headsmack!” moments, wherein I was struck by how resoundingly he missed every possible point, although because of his age and the nature of the assignment, who knows how much is reasonable to expect. To top it off, he’d intentionally attempted to defame his brother, which seemed to go against the very sentiments inspiring the assignment in the first place.

But then it occurred to me that the way he’d interpreted King’s words wasn’t really that different from the way that adults around him were doing it, presuming we focus on the maneuver and not the content. In other words, I’m not saying that I think most would find his interpretation of King’s words mainstream (i.e., raining cats), but in as much as he used King’s words as an avenue through which to express his own wishes, fears, and group alliances, his first grade mind was performing the same acts as his older interlocutors.

After all, would many who invoke King be comfortable with the degree of radical action that he incited in his day if they were to presently experience it? In his pacifism? In his support for public action campaigns that are, in some ways, astonishingly like the racially-inspired protests held today, those which are so divisively viewed by the American public? Because the likely answer is no, transforming his words into a more palatable incarnation is just one way that social groups give the appearance of change while remaining steadfastly committed to certain entrenched power structures. So when I mention “the point” of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day (or any other large group ritual) and the fact that my kid missed it, what I’m getting at is the irony that the point is always made in retrospect by those determining in the present how the past will be read.

Photo credits:thesource.com, quotesgram.com, The Sociological Cinema (via pinterest.com)