As I write this the fate of two citizens of Japan is still in question — kidnapped in Syria and threatened with execution if their government does not pay a $200 million ransom to ISIS.

An interesting feature of this story is the reaction in Japan to their abduction. As stated in this Reuters article:

On a more personal level, there remains a conflicting view of hostages in Japan, with greater sympathy reserved for those seen as “more victim” than others. At one extreme, for example, are those Japanese abducted to North Korea through no fault of their own….

Coming on the heels of the Charlie Hebdo murders in Paris, where advocates of the absolute right of free speech bristle when anyone even hints that the work of the satirical cartoonists might have provoked (but, of course, not justified) the attack, this reaction in Japan is curious.

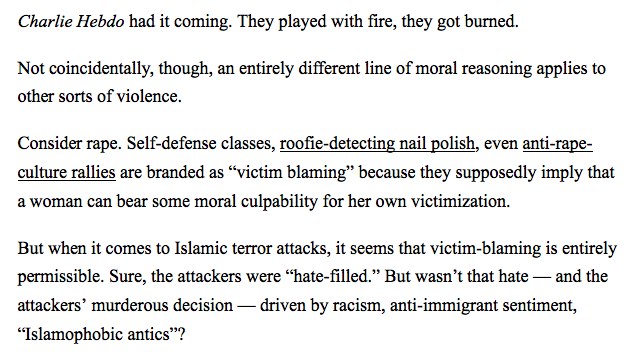

For example, consider this recent online article in the conservative US magazine The National Review; after quoting a White House spokesperson and a columnist in The Financial Times, both of whom suggest the Parisian artists’ own actions are relevant for understanding what took place, the article sums up this view (doing so somewhat sarcastically, I’d say) and then critiques it for the moral inconsistency of such a stand — an inconsistency that, the author claims, is due to liberals being soft on terrorism:

So what accounts for when we hold individuals responsible for their actions and when we don’t? Why might one think that certain social actors are accountable for their actions while others are so-called innocent victims who hold no blame? At least one of the Japanese abductees has been reported in the press to have had personal troubles prior to going off on his Syrian adventure, as a photographer, or is it a mercenary, independent contractor, or perhaps an arms supplier for Syrian rebels? — does that make him somehow less sympathetic, less of a victim, and, ultimately, less worth saving?

For, rightly or wrongly, there are indeed times when we say “He had it coming…” But when, and how, collectively, do we decide that someone is a helpless victim or, instead, is, to whatever degree, complicit in their fate, and thus not deserving of our help? Answering that question — a question of when we do or don’t ascribe agency and thus accountability to the actions of other agents — will not only help us to understand the public reactions to the Paris attacks and the abduction of these two Japanese men, but will also shed light on how many of us see anyone in a less fortunate circumstance than ourselves.

For it’s not hard to find someone who will argue that poor people are poor because they’re just lazy…. It’s their own fault.

Or is it?

Update: several hours after this was first posted it became clear that the gentleman in question, Mr. Yukawa, had indeed been executed.