“Look! . . . Up in the sky. . . . It’s a bird. . . . It’s a plane. . . . No, it’s Superman!” When someone points out something in the distance, like an object flying through the sky, it can be hard to recognize just what it is. We attempt to name it, place it in a clear category, but sometimes our categories don’t fit, especially when working with complex societies, and the category that we attempt to force it into often influences what we actually see.

“Look! . . . Up in the sky. . . . It’s a bird. . . . It’s a plane. . . . No, it’s Superman!” When someone points out something in the distance, like an object flying through the sky, it can be hard to recognize just what it is. We attempt to name it, place it in a clear category, but sometimes our categories don’t fit, especially when working with complex societies, and the category that we attempt to force it into often influences what we actually see.

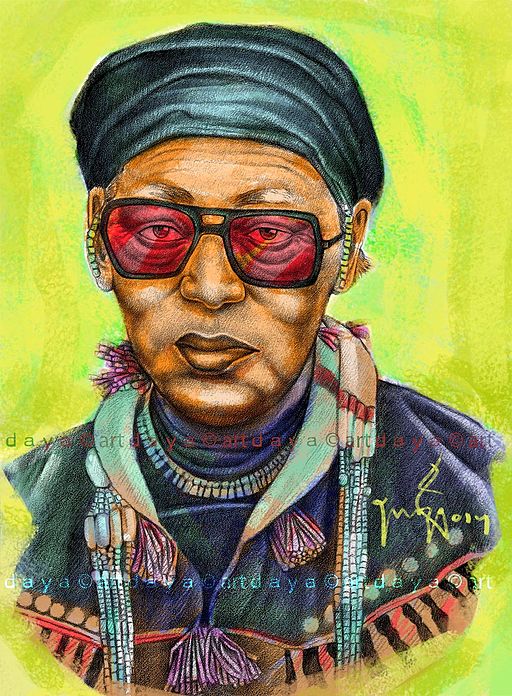

Arkotong Longkumer, in Reform, Identity and Narrative of Belonging (a 2010 book on the Heraka movement in northeast India), analyzes an intriguing community and movement that engaged politics, economics, social change, ritual shifts, and ethnicity, to name a few areas of interest. The context of the movement was the increasing imposition of British rule in the region in the early twentieth century, including the British encouragement of immigration to the area that disrupted the traditional migration cycle and the agricultural system that required it. The simultaneous opportunity for education and government jobs combined with the necessity of alternative forms of labor in the wake of declining agricultural production. All of this required a revision in ritual practices and social restrictions to reduce the expense of animal sacrifices and the limitations on mobility and individual independence from the community, as they adapted to the changing environment. The contexts also fostered interest in uniting different groups politically in opposition to, at times, the British and other communities. In fact, the image above of one of the leaders is entitled “Indian Freedom Fighter”.

In such a context, how do we describe this movement? While Longkumer acknowledges the absence of the term “religion” in the language of the Heraka and usefully illustrates its various interests and aspects, he chooses to focus much more on ritual practices, beliefs about the divine and creation, myth, prophecy, scripture, millenarianism, and messianic expectations, all elements that commonly fit within a religious studies frame, than the political, freedom fighting elements that the artist emphasized. Despite acknowledging problems with the term “religion,” his analysis, while useful, imposes the common sense of what counts as religion onto this movement that, as his ethnography demonstrates, breaks the bounds of any of these distinct categories. Any researcher must choose what elements to emphasize. His work (revised from a PhD dissertation for Continuum’s Advances in Religious Studies Series) falls into the disciplinary trap that tends to restrict our questions and analysis. Interestingly, the Heraka community at times also adopts similar constructions. In fact, as he presents the movement, it shifts the focus from communalism to individuality in a similar way to privatization of belief and practice in modern Euro-American conceptions of religion. So, the hegemony of these constructions of religion influence both his description of the movement and aspects of the movement itself.

Similar questions can also be asked of the other communities engaging the Heraka movement. Various Naga Christian denominations (which sometimes marginalize non-Christian Nagas in their political efforts to obtain greater autonomy for Nagas) and Hindutva organizations (attempting to unite non-Christians and non-Muslims, including the Heraka, as the true ethnically Hindu nation) all intersect with a variety of aspects of society, politics, economics, and various designations of ethnicity and nationalism. The simple analysis of any of these as religious movements is similarly problematic.

A range of theoretical works, including some that Longkumer cites, call for scholars to avoid naturalizing the hegemony and instead interrogate and complicate it. Analyzing more deliberately the ways such movements adopt hegemonic categories (and how this influences these movements) would be one approach. Pushing this further, taking those theoretical works seriously should lead us to further question our own assumptions and develop different frames that will generate different insights and questions rather than pushing complicated movements and communities into narrower, disciplinary frames.

Artist’s image of Gaidinliu (one of the leaders of the Heraka movement) Titled “Indian Freedom Fighter” by Dhayanithi (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons