Darth Vader vs. Luke Skywalker, Sauron vs. Gandalf, Voldemort vs. Harry Potter. Stories are full of good and bad characters, sometimes complicated with the redemption of a character like Darth Vader, but what does it take to maintain such a stark division between good and evil?

Darth Vader vs. Luke Skywalker, Sauron vs. Gandalf, Voldemort vs. Harry Potter. Stories are full of good and bad characters, sometimes complicated with the redemption of a character like Darth Vader, but what does it take to maintain such a stark division between good and evil?

The early twentieth century novels by Sax Rohmer presented such clear contrasts between civilized Europe and evil threats from the East. While his famous series of Fu-Manchu novels focused on the “yellow peril,” his novel The Quest of the Sacred Slipper (published 1913, 1914) emphasizes the threat of the Hashishîn, whom he identifies as Muslims from Arabia. (The term assassin coming from this label, they have been an object of fascination and political rhetoric for centuries in Europe, as Bruce Lincoln analyzes in his chapter in Writing Religion.)

In this Rohmer novel, Professor Deeping steals a relic, the slipper of Muhammad, and brings it to London to place in a museum. While the main character, Mr. Cavanaugh, is uncomfortable with Deeping’s methods of acquisition, Cavanaugh becomes custodian of the slipper, at Deeping’s request, after the Hashishîn murdered the professor. In Rohmer’s account, the Hashishîn are fanatic, evil, violent, deadly. Another character, an American crook trying to steal the slipper himself, is a genius criminal, difficult to catch but deserving of jail. In contrast, the professor is, at worst, a bit misguided. Following a colonialist rationale, where those with power saw themselves as benevolent patrons, protecting people and preserving history, no one suggests that the professor should have been arrested for theft, and the authorities follow his wishes rather than return the relic to its prior owners. The illegal methods, at least illegal if used against other citizens of England, are excusable because they are seen as serving a greater good.

Of course, such descriptions have some logic, based on Rohmer’s narrative. The tactics of the Hashishîn, including severing hands and murder, are more violent, and the American crook is working for personal gain, while the professor works to extend knowledge and preserve an ancient past. Constructing the descriptions in this fashion, though, overlooks the violence that maintained status and power differentials that facilitated the professor’s access to steal the relic. The state’s monopoly over the use of violence is one naturalized component, but much of the British empire’s power, even in areas outside its direct control, was extra-governmental, operating initially through corporations like the British East India Company. Later, the power of the state still derives from the resources developed in the private sector through lucrative trade and exploitation, which swelled the coffers of the state. So the violence that narratives like Rohmer’s overlook goes well beyond the direct action of any government.

These observations are not too far from the competing social media posts last Friday. While many people mourned the tragic losses on 9/11, different people wanted to expand the memorialization to include Iraqi and Afghani civilians killed in the War on Terror, lives lost to police brutality, or other victims of gun violence, among others. But even these expansions ignore others whom the economic structure treats as expendable, such as factory workers in sweatshops across Asia and laborers extracting oil and coal within the United States. In other words, everyone who posted on social media, competing over which lives we should remember on 9/11, depend on the cheap(er) electronics and energy that make some lives expendable. As in Rohmer’s novels, that pernicious violence is an integral part of the structure of our society that often remains hidden, allowing us to see our society and ourselves as good and peaceful while turning a blind eye to the violence supporting it. While tidy stories of good and evil are much more satisfying, that comforting narrative device helps people overlook the violent structures that benefit many of us.

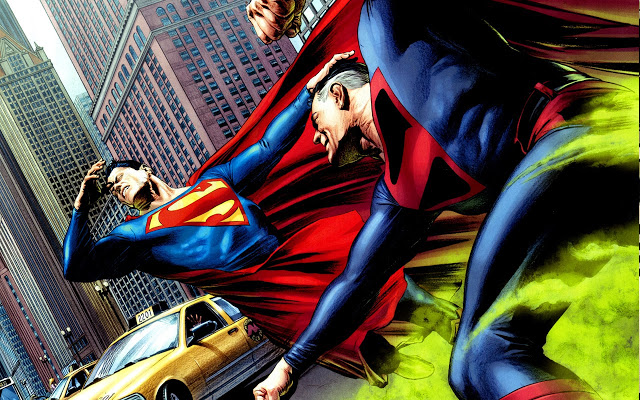

Image credit: “Superman: Good Vs. Evil” from 2Top (CC-BY-2.0) via Flickr