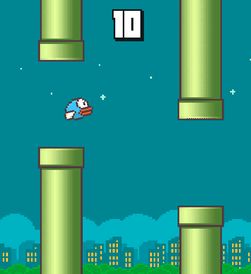

The recent fad of Flappy Bird, and its removal by the independent game creator, has raised some significant angst. Why has such a simple, low budget video game enraptured people so much that they consume hours of their day trying to beat their high score, like a movie buff with a limitless supply of popcorn? If you have not experienced its addictive power, this homage to Flappy Bird can give you a sense of its power. (It certainly made writing this post take longer than it should have.)

The recent fad of Flappy Bird, and its removal by the independent game creator, has raised some significant angst. Why has such a simple, low budget video game enraptured people so much that they consume hours of their day trying to beat their high score, like a movie buff with a limitless supply of popcorn? If you have not experienced its addictive power, this homage to Flappy Bird can give you a sense of its power. (It certainly made writing this post take longer than it should have.)

Faced with the angst that its surprising popularity has generated, people have employed a little categorization to help us order our experiences of the world. Will Oremus at Slate recounts several answers from others before presenting his own.

Some insist that it was in fact one massive, societywide in-joke. The gaming site Kotaku wrote it off as a senseless fad, like Beanie Babies. The Independent wondered if it was actually art.

. . .

A game that you play for the sake of real-world advancement is not really a game at all—it’s “gamification.” Real games are played to divert us from our workaday responsibilities, not pad our resumes or thicken our wallets.

To make sense of his world, Oremus emphasizes this narrow notion of a game. What is the source of this definition? While he references “the Platonic ideal of Game,” I doubt that a transhistorical conception of “game” exists. Rather, the label “game,” and the conception that he presents to define the label, are human constructions in the service of ordering his experiences. In other words, his analysis is not simply describing the world but constructing the objects that he wants to describe. Of course, the moving pixels of light that responded to his taps on his iPhone preceded his description, but the notion of those moving pixels having something in common with bouncing a rubber sphere on a piece of wood is his construction, building on the ideas of others within society.

Oremus concludes his article by referencing “our human need to concentrate for a moment, an hour, or an evening on something other than the weighty complexities of real life.” Isn’t this category “human” similarly a construction of the author, highlighting particular presumed commonalities that help order (and universalize) aspects of his own experiences. While these assertions look like descriptions of the world, they, like other aspects of communication, including academic analysis, construct the objects, categories, labels, that the author presumes to be describing.

Image by ManuBu (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons