Sitting in a hotel meeting room in downtown Atlanta the weekend before Thanksgiving, I watched a professor ask one of my colleagues if the Civil War really happened. This question reflected an effort to challenge the approach that sees scholars and language creating the world. (For an example of this approach to history, see Vaia Touna’s posts here and here.) The questioner here also emphasized a distinction between history (stuff that really happened in the past) and historiography (the writing about the stuff that happened), suggesting that a focus on analyzing historiography ignores the reality of the events themselves.

Sitting in a hotel meeting room in downtown Atlanta the weekend before Thanksgiving, I watched a professor ask one of my colleagues if the Civil War really happened. This question reflected an effort to challenge the approach that sees scholars and language creating the world. (For an example of this approach to history, see Vaia Touna’s posts here and here.) The questioner here also emphasized a distinction between history (stuff that really happened in the past) and historiography (the writing about the stuff that happened), suggesting that a focus on analyzing historiography ignores the reality of the events themselves.

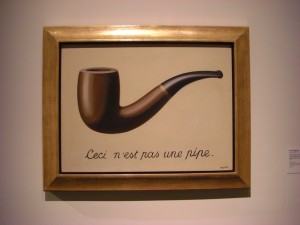

The photo above of a reenactment of the Civil War in 2009 becomes an interesting object to think about in relation to these questions. Even as the photographer adjusted the image to be black and white with a dark edge (I assume to make it look old), we easily recognize that this photo is not the Civil War but a recent reenactment of an event labeled as part of the Civil War. As a photo of some stuff that happened about 6 years ago, though, we also can easily distinguish between the photograph and the reenactment itself. The photo is like historiography. Someone used a camera to take the image and, in that process, cut out a whole range of actions, people, and objects outside the frame that the lens provided and all the things that came before and after the moment captured. The photo is not the history, to paraphrase Jonathan Z. Smith, and, like in Magritte’s painting below, the image is not the same as the object depicted. (For an interesting expansion on the complex layers of difference here, see Michel Foucault’s book This is Not a Pipe.)

To push this point further, the label “Civil War” is like the photograph. It represents an entire series of things that happened with a simple term, but it is not the events themselves. In the area around Atlanta, some people (at least at one point in time) called those various actions, things, people, etc., the “War of Northern Aggression” because that label better reflected their perceptions of that series of events. The name that a person chooses to use is their choice, reflecting their background, assumptions, etc., and is not a simple description. When we describe something, our words do not become whatever we try to describe. The words reflect the choices of the speaker/author to decide which elements are important, what events are included within the period of the “Civil War.” Thus, they also decide which things fall outside the conflict, left unrecognized on the cutting room floor that is an important aspect of our mental capacity. In fact, even naming the time period (1861-1865) not only establishes clear boundaries for the inclusion of events but also conveys those boundaries through the arbitrary (yet extremely useful) system of dating.

The assertion that scholars and others construct the world does not deny the existence of physical objects or events past and present but emphasizes how we can only analyze and engage the world through language, naming, describing, debating the things around us. We cannot access the specific events themselves, the history; we can only access the historiography, the description of the events in language (as well as image), making such descriptions the place to focus analysis. In fact, my account of the panel in Atlanta that I witnessed just over one week ago itself is historiography (and probably contested historiography). The panel really happened, but my description of it (and counter-descriptions from others) are the only ways we can engage it now.

Image credits: “Civil War Days in Illinois” by Mark Theriot (CC BY-SA 2.0) via Flickr

Photo of Magritte’s Pipe by Jay Cross (CC BY 2.0) via Flickr

Good post.

I have quick lexicographical quibble. As I told the professor after the meeting in question, I prefer that we use these terms history and historiography differently.

Time seems to exist and we all distinguish between the present of our living selves and what happened before us. But what happened before is not properly termed “history.” What happened before, which we might choose to assert “really happened” is “the past.”

“History,” on the other hand, from the Greek word for “inquiry” is a genre of discourse. It is the writing (usually a writing) which constructs a meaningful narrative about the past.

“Historiography” is generally used to refer not to the writing of histories, but to writing about them. It is inquiry into the inquiry. At its most basic, it is a lit review. At its most complex, philosophy, theory and critique of “history.”

These terms are of course fluid and to use them with any fixed meaning you would have to stipulate that meaning as assumed. That’s the set of assumptions I prefer.

The advantage of speaking this way is that you draw a clear line between some postulate of theoretical physics and experience (“there are past events”) and the social fact of “history” which is inevitably a contestation about the past, even as it poses as an attempt to discover “what really happened.” “History” isn’t “what really happened” but an inquiry into the past guided by that question. And to the extent that we have any hope at all of remembering the past “accurately” (according to the transcript of some kind of transcendental, universal memory, I guess?) it would be through “historiography,” as we sift and compare and decide among the competing “histories” that are preserved in our “present.”

An excellent article! This raises a “good many ” questions concerning both the recent controversies over the Confederate Battle Flag and over the historical events that are important to people practicing any given religion. It is far too tempting in this age of political correctness to use history as a weapon against those opposed to you on modern grounds. How many thousands of Confederate Flag supporters were called racists while they were on their knees praying for the families hurt in the Charleston shooting? By denying that history can be interpreted differently by different people the Flag detractors impose their political will on others illegitimately. If examined closely, it is similar tactically to what the so-called “radical” atheists do in saying there is no evidence for the existence of Jesus of Nazareth ; it’s the imposition of one viewpoint on the past in order to repudiate any other viewpoint in the present. Another example would be the destruction of the Buddhist statues in Afganistan by the Taliban in order to “change” the past and validate the worldview being imposed on others.

Tom Bryant

MA – Religious Studies, Univ. of South Florida

Thanks for your comment. The preferences that you present can work to clarify some of my points, certainly. Referring to “the past” as you define it might make my point clearer. However, often the distinction that you make between history and historiography becomes fuzzy in my experience, as many histories remain in conversation with other histories, critiquing/correcting them, which blurs that line.

You are certainly correct that historical narratives become weapons, used by all sides, in the political contests that surround us. Opponents of the Confederate Flag and those who interpret it differently have all used competing narratives about the Civil War to promote their position. For me, the issue with the Confederate Flag is less about the past and more about the ways it serves to marginalize some, largely based on race today, but the overgeneralization that anyone who defends the Confederate Flag is racist is a problematic view of the ways symbols function, as I have written before. I notice that the term “political correctness” also functions for some to dismiss calls for change that they oppose, so it too becomes a symbol in these contests.

I think you’re right about the blurry distinction between history and historiography. But there’s little doubt in my mind that “history” is a discourse genre (as is historiography) and should not be conflated with “what happened.” Once again to paraphrase Smith as you did, the history is not the past. The past can be a subject of our discourse, of our inquiries (histories), but it is itself not discourse nor reducible to it. We can believe that there is a “real” past (it is a belief). In that sense I absolutely would say, yes there really was an American Civil War (even if we disagree on what to call it, or even what dates to assign it). But there’s no basis for believing that any “history” written about it can fully represent it, let alone be stamped with the claim “this is what really happened.”

As for the claim that “history” and “historiography” are hard to distinguish, as I said, I agree. But I would point out that published books regularly subtitle themselves “a history” (as a genre label, compare: “a novel”) but almost never “a historiography.”

Yes, “the history is not the past” is probably a clearer assertion of this point. To use that distinction, though, naming a set of past events “the Civil War” is history (ie, discourse), so the Civil War does not exist without people constructing sets of events in the past as the Civil War.

Yes. Touché.