Responding to census questions is not simply reporting already self-evident identifications. The process of asking the questions creates those identifications and the groupings that organize the census data. The current census effort in Australia, scheduled for today, illustrates this point quite clearly. Due to the increasing number of respondents reporting “No religion” on the voluntary religion question, census officials have shifted that response to be first on the list of possible responses, which has generated competing campaigns to influence how people identify themselves, and thus the results of the 2016 Census.

Responding to census questions is not simply reporting already self-evident identifications. The process of asking the questions creates those identifications and the groupings that organize the census data. The current census effort in Australia, scheduled for today, illustrates this point quite clearly. Due to the increasing number of respondents reporting “No religion” on the voluntary religion question, census officials have shifted that response to be first on the list of possible responses, which has generated competing campaigns to influence how people identify themselves, and thus the results of the 2016 Census.

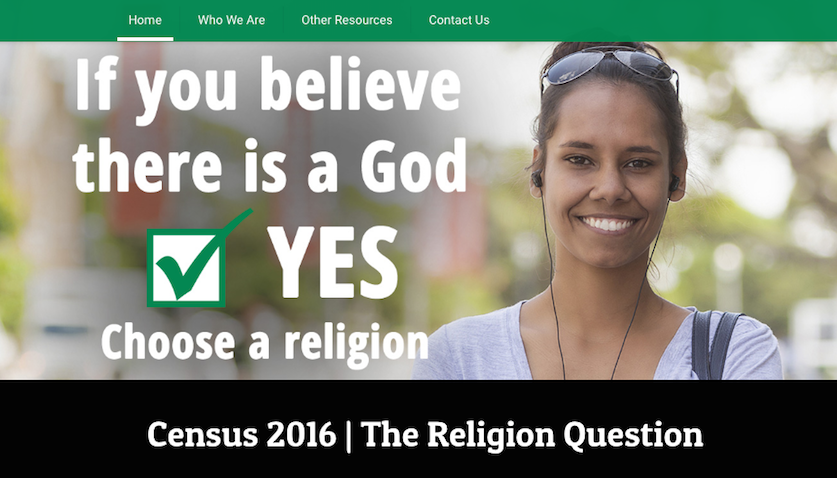

Some campaigns have encouraged people to mark “Christian” rather than “No religion,” employing a range of intriguing arguments. Most bizarrely, some have asserted that the drop in the percentage identifying with Christianity means that Australia could eventually become a Muslim nation (even though Muslims in 2011 were only about 2% of the population). In a less fantastic assertion, some, including several organizations identifying with Christian proselytizing, suggest that most people can identify as Christian, even if not actively participating in a congregation, because few in Australia actually deny the existence of God (thus implying that “No religion” equates to “Atheist”) and most come from a family that identified with Christianity and hold values that they identify as Christian.

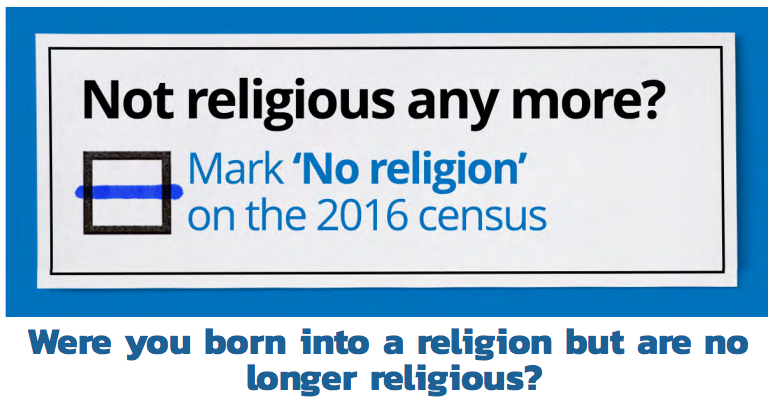

On the opposite side, some in Australia are encouraging others to mark “No religion,” including discouraging people who do not identify as religious from writing in “Jedi,” which they see as a viral practical joke with problematic outcomes. Part of their interest in making this argument has nothing to do with Star Wars. They want to bolster a political argument that those who are not religious should not subsidize religious communities through tax breaks and government spending policies on social services run by religious institutions and chaplaincy programs. Increasing the number who identify as “No religion” furthers the argument, and the political power of those groups who claim to represent those who are not religious, such as Atheist Foundation of Australia.

On the opposite side, some in Australia are encouraging others to mark “No religion,” including discouraging people who do not identify as religious from writing in “Jedi,” which they see as a viral practical joke with problematic outcomes. Part of their interest in making this argument has nothing to do with Star Wars. They want to bolster a political argument that those who are not religious should not subsidize religious communities through tax breaks and government spending policies on social services run by religious institutions and chaplaincy programs. Increasing the number who identify as “No religion” furthers the argument, and the political power of those groups who claim to represent those who are not religious, such as Atheist Foundation of Australia.

As several of us in Culture on the Edge have argued before (e.g., here, here, and here), those lumped together as the “nones” based on their response to one survey question are not only quite diverse but also do not form a group until analysts force them together. With the current lobbying efforts in Australia, it becomes clear that these presumably self-evident identifications and groups are not so self-evident. People disagree about who should respond in a certain way and what each label means. The influence of the order of the options on the census, which is a part of the impetus for these competing campaigns, highlights how the census is not simply measuring something that is pre-existing and self-evident. Beyond the government funding implications of the analysis of census data and its use in policy arguments, the discussion of census data can begin to generate the groups that a census presumably measures, as people are told what group they should mark. The group does not exist until someone labels them and counts them.

As the campaigns and debates surrounding the 2016 Australia Census illustrate, a census is not measuring the shifts in religious practice and behavior but shifts in how people respond to census questions. The effort to measure identifications ends up creating, and changing, them.

Image credits: Screenshot from YesReligion.org.au website

Screenshot from Mark No Religion campaign poster (Census No Religion website)