It occurred to me sometime ago that when we pour something we’re not actually pouring anything. Continue reading “Misattributions”

A Peer Reviewed Blog

It occurred to me sometime ago that when we pour something we’re not actually pouring anything. Continue reading “Misattributions”

As tends to happen near the end of every Spring semester, I find myself returning to my favorite commencement speech, offered to Kenyon College’s 2005 graduating class by the late great David Foster Wallace. I refer it to students for whom thoughts of graduation and of what their next professional or academic move(s) will be loom large. I even play it for my classes sometimes.

It’s still useful outside the context of graduation, though, so I thought I’d share it here at Culture on the Edge. Wallace talks about how we make meaning in quotidian contexts and about the utility of some critical self-awareness in the process. Thinking through what we assume to be obvious and what we so often take for granted, he suggests, makes up the hard work of cognitive creativity — the work for which a liberal arts education provides some useful tools.

So let’s talk about the single most pervasive cliché in the commencement speech genre, which is that a liberal arts education is not so much about filling you up with knowledge as it is about ‘teaching you how to think’. If you’re like me as a student, you’ve never liked hearing this, and you tend to feel a bit insulted by the claim that you needed anybody to teach you how to think, since the fact that you even got admitted to a college this good seems like proof that you already know how to think. But I’m going to posit to you that the liberal arts cliché turns out not to be insulting at all, because the really significant education in thinking that we’re supposed to get in a place like this isn’t really about the capacity to think, but rather about the choice of what to think about. If your total freedom of choice regarding what to think about seems too obvious to waste time discussing, I’d ask you to think about fish and water, and to bracket for just a few minutes your skepticism about the value of the totally obvious.

Give it a listen. Among other things, it will help you take a second look at this afternoon’s grocery run.

For a new Culture on the Edge series “You Are What You Read” we’re asking each member to answer a series of questions about books—either academic or non-academic—that have been important or influential on us.

5. What’s a book that you love but which isn’t widely read?

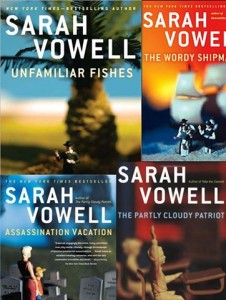

Anything by Sara h Vowell.

h Vowell.

While enjoying her dry wit and occasional sarcasm, what I love so much about Sarah Vowell’s writing is that it is widely accessible yet incredibly well researched, making her the ideal example of what some of us aspire to do (perhaps on a blog such as this even?): reach wide audiences with our scholarship. While not thinking that this is the sole audience, or even a required audience, to reach, for anyone wanting to write for wider audiences than just other scholars or other scholars-in-the-making (regardless what level they are in school), Vowell’s books present the model for how to do this. She strikes me as a poster-child for the relevance of the Humanities, in fact—a much discussed topic these days—for her 1993 B.A. from Montana State University in Modern Languages and Literature and her M.A., earned at The School of the Chicago Art Institute in 1996, in Art History are both in areas that, at least according to some, have little direct relevance for employability. Yet here she is, a widely selling author (even the voice of the daughter, Violet, in the animated film The Incredibles!) whose engaging books dive deeply into terribly complicated and, at times, controversial historical material—I think back to a sad, funny, troubling, and, ultimately, incredibly engaging story she did in 1998 on her and her twin sister’s summer travels along the Trail of Tears or her 2003 dissection of the tangled history of The Battle Hymn of the Republic, each remarkable pieces of history writing—but doing so in a way that makes the storyteller’s (or, in the case of the latter, the singer’s) own conflicted positioning part of the narrative as well.

So pick up one of her books, and see what you think—you may find them to be far more relevant for scholars and students that you might at first think, either as an example of how to write for wider publics or as an example of the skills that we in the liberal arts daily teach to our students (sometimes without even knowing it).

Along with your morning coffee,

Along with your morning coffee,

we’re hoping that a regular

dose of critical thinking

gets your day off

to the right start.

You’re welcome.

You’re welcome.

@idendefying

Read more.

Read more.