This semester I’m teaching an introductory course on the Study of Religion, that is, looking at scholarly definitions and scholarly approaches to the study of religion. We’re exploring among other things, together with my students, questions like what is the study of religion? What is at stake in naming/defining/classifying things in this or that way? Although this early in the semester one question that prevails is:

This semester I’m teaching an introductory course on the Study of Religion, that is, looking at scholarly definitions and scholarly approaches to the study of religion. We’re exploring among other things, together with my students, questions like what is the study of religion? What is at stake in naming/defining/classifying things in this or that way? Although this early in the semester one question that prevails is:

What is it that we study when we study religion?

I cannot stress enough how many times, using a variety of examples (some interactive, others not so much), I repeat myself by saying that in this course we are not interested in whether something IS sacred, or religious, or holy BUT we are interested in the people classifying things in this or that way. In other words, we are not looking at the thing itself and whether or not it possesses such a quality but we are looking at the people who do the naming and often times we are looking at the people who critique a particular naming.

As I was preparing for my next class in which I was considering how to further make the point that our concepts and the definitions we ascribe to them are ours and we should be cautious when we are projecting them both in other places but also backwards in time — because the danger we run into, especially as students and scholars of religion, is that we often assume (like the people we are studying) that our concepts correspond to their meanings; our concepts therefore are thought to transcend space and time and are therefore universal. And of course the point being that if we name a thing or a behavior as, say, religion or religious then this naming may tell us more about us and our interests than about the thing or behavior we are naming.

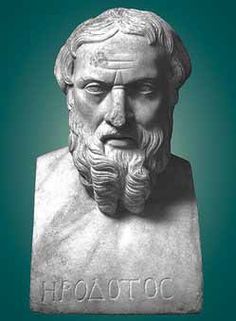

Now in trying to come up with a good example to make evident even more this point, I thought about bringing in to class the example of “history” and the very well known ancient Greek historian Herodotus. The term “history” is itself, like the category “religion,” a term that is contested among scholars as to what it means and, of course, like all words its usage and meaning has changed over the course of time. In order to make my point consider that often times Herodotus is judged by some modern historians as not doing “real historiography,” because, as the arguments goes, in his narrations he inserts fantastic stories and, well, he doesn’t stick to the “facts.” But this argument is based on a very modern definition of what writing history is and by this modern definition Herodotus is anachronistically judged as not a real historian.

Now it is not so much as to whether Herodotus is a real historian or not but that in this critique by those modern historians we may learn more about the interests of those modern historians — maybe something to do with authorizing what it is they do: modern historiography — as to what is or not a historian, or historiography and less so about Herodotus.

But Herodotus is also a great example because in Greece today (and not only of course) he is also referred to as the first “Greek” historian; it is not unlikely that “Greek” here is understood as possessing a quality that transcends time and space, which further shows a contemporary interest in making the modern Greek nation-state appear eternal; for when Herodotus, who was from Halicarnassus (an Ionian city at the Aegean coast of Asia Minor [today being the city of Bodrum in Turkey!]), wrote about Greeks in comparison to what were then known as Persians, it is not difficult to read as having a different understanding of Greekness than what modern Greeks mean by it.

So, looking around the internet about Herodotus, I came across an article on the online version of the Encyclopedia Britannica which gives a short summery of Herodotus’ biography and his qualities as a historian. As I reached the conclusion I was particularly surprised about the way Herodotus was identified:

But these predecessors, for all their charm, wrote their chronicles of local events, of one city or another, covering a great length of time, or comprehensive accounts of travel over a large part of the known world, none of them creating a unity, an organic whole. In the sense that he created a work that is an organic whole, Herodotus was the first of Greek, and so of European, historians. His work is not only an artistic masterpiece; for all his mistakes (and for all his fantasies and inaccuracies) he remains the leading source of original information not only for Greek history of the all-important period between 550 and 479 BCE but also for much of that of western Asia and of Egypt at that time.

Herodotus was not only the first Greek historian BUT also the first European. Reading that I immediately thought to myself, “Ok now you have taken it a bit too far,” European? Really? But I also thought that here is another good example of an anachronistic use of “European” by an author who tried to identify the origins of modern European historiography in the Greek past.

But what is of particular interest to me is that even though I was able, given my interest in anachronisms, to be careful or self-aware when I say Herodotus was a Greek, the fact that I was so surprised and I was immediately ready to dismiss and critique the designation “European” as a false identification of Herodotus, I realized that someone cannot easily escape where one comes from; for assumptions that have to do with Greece and the modern Greek nation-state, as having a different (special?) history from that of the rest of Europe, assumptions that I was not so ready to give away (especially given what’s going on the last few years in Greece and in relation to the European Union), may tell you a lot about me, and what I perceived to be the stakes for my own identity when someone reclaims and repurposes Herodotus as “European,” telling me more about myself than about Herodotus or even the authors of that article.

In other words, a past is also shaped in direct relation to identification contests in the present — whether projecting backward a modern sense of national identity (Greekness) or even of a scholarly method (writing history). If so, then it will make sense not to look at the past actors and how they are being named but look instead at who and for what purposes they are named this way or at who contests their names.