Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson has once again irked humanities scholars. In 2014, he had declared philosophy a “useless” enterprise (a stance his colleague Bill Nye once held and has since revised). This time Tyson drew backlash for what he didn’t say.

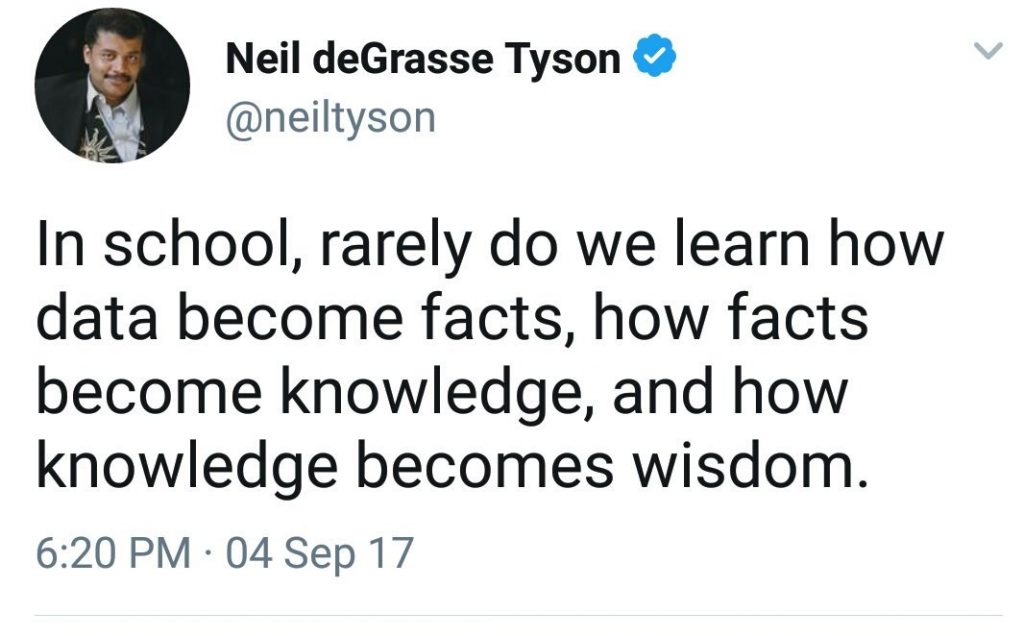

The public intellectual tweeted about the lack of educational enterprises helping students discern the construction of “facts” and “data” in an age of “fake news.” Tyson has long been an advocate of meta-cognitive pedagogy. But the tweet’s concise pronouncement suggested that no one is doing that work.

[Enter the Humanities.]

https://twitter.com/prof_gabriele/status/905067457999765505

Hi Neil,

That's literally what we teach.

Thanks for the shoutout!

Sincerely,

The Humanitieshttps://t.co/hVphWKDzbj

— Librarianshipwreck (@libshipwreck) September 6, 2017

Point well-taken. This choir member appreciates the sermon.

The clapback has since reverberated throughout the humanities’ echo chambers. But is the riposte so snappy on the second listen?

Do the humanities have a track record of analyzing how we know what we know and like what we like? Sure, but it’s not as storied as the legion of curricula that forget Jonathan Z. Smith’s maxim on the introductory course.

Whether in the mass commendation of “great books” or the anthologizing of various “classics,” the humanities have plenty of proponents of self-evident truths.

And for all of our commentary on how to make sense of these truths, we still seem beholden to the canonical impulse of distinguishing the primary from the secondary source. If anything, many of our publics are literally just discovering the political ramifications of their favorite stories.

For instance, the once-fringe critiques of racialized mainstream historiographies are just beginning to be taken seriously. But whether its Dr. Sarah Bond’s discussion of how Greek and Roman statues become “white” or Dr. Kelly J. Baker’s analysis of the Klan’s Christian identity and influence, there’s often hell to pay when we ask, “how do you figure?” There is littler wonder as to why having a syllabus from a minoritized group is noteworthy. We too easily forget that no history is more forced than those that sublimate difference.

All this to say: maybe such theorizing about data is figuratively the work of the humanities. Tyson’s tweet was simply a backdrop for projecting a scholarly future we are just learning to create for ourselves. It also happens to be the version of our field we are quickest to showcase.

This all makes me wonder about the versions of the humanities we are so quick to hide. And if we don’t contextualize those versions, are we not guilty of what Tyson has implied?

… because there’s always a backstory. Go figure!