By Andie Alexander

“So are you a political activist now?”

I’m not the kind of person who often posts on Facebook about politics. After all, I’m still a grad student hoping to get a job one day, and there’s no telling what sorts of ideas people could formulate about me based solely on my Facebook posts. With that always in the back of my mind, I tend to keep my posts mostly about the academic study of religion (well, that, and pictures of my dogs, obviously, because they’re adorable). However, over the past few weeks, I have been sharing significantly more news articles and reports on my Facebook page. In the wake of this exponential increase in the number of political articles and photos from the Denver Women’s March (see above) on my page, folks were somewhat surprised with my seemingly sudden interest in politics. So much so that some have even called me a political activist.

When others heard these comments about my newfound activism, some agreed in a positive way, while others maintained that I was not a political activist and that I was just sharing information. However, what struck me about these comments was not whether I really am/am not a political activist — to me that misses the point. Rather, I am more interested in this label or designation of “political activist.” For the more I thought about it, I realized that this identifier rarely has a positive connotation.

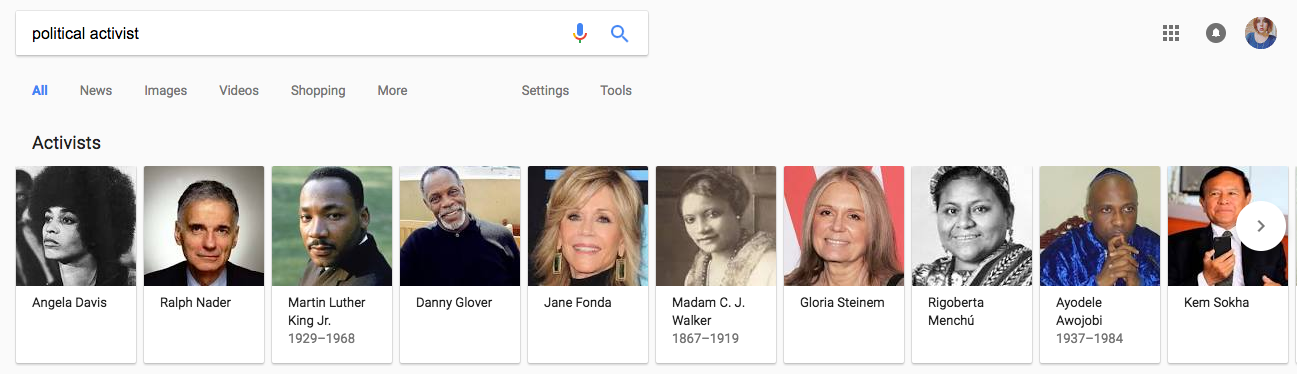

Naturally, I decided to “go to Google” to see what constituted a “political activist.” When I Googled this, the above photos appeared at the top of the page. What I found particularly intriguing about the initial set of people Google had listed as political activists was that the majority of them were people of color and women, or put differently, people who are marginalized to varying extents. Now that is not to say that this is an (in)correct description of a political activist, but it is rather telling. The people shown are/were fighting the status quo, whatever that may be, and therefore are often regarded by those in power (in the center) to be radical outsiders (on the periphery). I say radical not because these so-called activists are necessarily radical, but by even being labeled as an activist, one is labeled as an outsider (i.e., not one of “us”) who is challenging the norm.

Put differently, if one were to advocate for the views of the center, or the group in power (for the sake of argument, let’s talk about the U.S. government), they would likely be regarded by fellow group members as good citizens or patriots, whereas one on the periphery speaking out against the majority (read: dominant group) is labeled a political activist and regarded as radical, threatening, or subversive.

However, perhaps we can agree that nothing is this black and white. Instead, these rhetorical distinctions serve a purpose. Sticking with current politics, from a different point of view, Women’s/LGBT/Black Lives/Immigration Marchers are no more activists than they are good citizens, and Trump voters (who themselves constitute a minority of the U.S. adult population, making them a minority group) are no more patriots than they are radicals. No doubt every subgroup within the U.S. will label their non-members as subversive because this is, after all, how social groups function. And in this instance, by labeling one as a political activist (read: radical), those in the center, or members of a dominant group, are able to other and delegitimize their political counterparts. Rather than bridging differences, these rhetorical devices work quite well to build walls and divide what can be seen as competing social groups. So, by dismissing the “other” as radical, the center can maintain its grasp on power.

These moves certainly have an effect, whether it’s labeling people as delicate snowflakes or dangerous fascists. These are, to me, very deliberate moves made to divide and delegitimize the claims and concerns of others, as a way to rally supporters around a cause. So whether I am a political activist really isn’t the question — for the signifier has nothing to do with me, and everything to do with the aims of the one doing the naming. For being labeled as such by someone who, I assume, disagrees with my political views, works to undermine my ideas to others who would also consider me to be radical. So if we can understand the sorts of rhetorical moves being made and how they work to undermine and delegitimize these marginalized groups (and admittedly, those in the dominant groups as well), perhaps we can reevaluate the ways in which we approach political strife.

So am I a political activist?

You tell me.

.

Andie Alexander is an M.A. student at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her research focuses on identity construction, discourses on classification and boundary construction, the practicality of definition, and public/private discourses with regard to issues of social group formation and nationalism in the U.S. She also contributes to the Studying Religion in Culture Grad blog. Read her posts here. Andie is also the Online Curator here at Culture on the Edge.