A recent news story has many, especially those in academia, buzzing and debating. Some of the (sensationalist) headlines read:

A recent news story has many, especially those in academia, buzzing and debating. Some of the (sensationalist) headlines read:

2) “University Prof Keeps Job After Newspaper Reveals Shocking Secret”

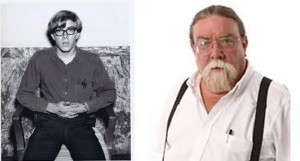

The first sentence of the first story included just the right recipe of words for juxtaposing St. James’s identity over and against his past and present, it reads, “…connected the dots between the 61-year-old’s peaceful life as an academic and his violent past as Jim Wolcott, known murderer.” A journalist from the Georgetown Advocate even had the opportunity to sit down with the St. James, at a bar, and interview him.

The short of the long is this:

“St. James, who at the time was known by his given name of Wolcott, murdered his parents and sister in their Georgetown, Tex. home in 1967, according to the Advocate. Huffing airplane glue and professing to be mentally ill [at the time of the murders], the 15-year-old St. James was ultimately found not guilty of his crimes by reason of insanity and ordered to be hospitalized until he ‘became sane.’ He would be released six years later and go on to pursue multiple degrees in psychology.”

After release from the hospital in 1976, St. James filed for a legal name change, which is why the university was only recently made aware of St. James’ past. Although some are calling for his resignation, the university released the following statement of support:

“Millikin University has only recently been made aware of Dr. St. James’ past. Given the traumatic experiences of his childhood, Dr. St. James’ efforts to rebuild his life and obtain a successful professional career have been remarkable.”

This story has sparked some interesting and curious conversations and statements on a variety of social media sites. A few posted on one Facebook a few days ago caught my eye:

1) “…..it is a big mistake to assume that an ethicist is moral as it is to assume that a psychologist is mentally stable.”

And then, a humorous one:

2) “I killed my entire set of plastic army men with firecrackers when I was 9. I’ve never told this to anyone.”

What do we make of how historical memory, time and space factor into such discursive constructions of identity?

Consider the first few sentences from the first headline that do the work of suggesting how readers ought to view this man, where the writer pairs together “peaceful” with “academic,” suggesting an already operative assumption about academic gentility and rational actors. The headline also pairs “violent” with “past” reminding us that St. James’ violent activities were a part of said past and not representative of his present. In a few swift key strokes, the headline situates St. James as successfully rehabilitated, productive in establishing a career, and no longer a menace to society. After all, the statement of support released by university officials can accept his past with ease given “the traumatic experiences of his childhood.”

Then, there’s the dilemma of “ethics” that many have chosen to ponder. Consider comment #1 that suggests one cannot assume that an ethicist is moral or that a psychologist is mentally stable. This comment presupposes that 1) we are our fields of study and 2) there is a way to tap into descriptive attributes of what certain fields ought to represent (“moral” and “mentally stable”). In other words, who we are (judged according to social norms) in the past determines and says something about who we are in the present. From such sentiments, there is little luck for rehabilitation. The headline’s effectiveness is offset by an ontologizing of scholars as their scholarship, (or plumbers as their plumbing, murderers as their murdering, etc., etc.) With this perspective, perhaps once a criminal always a criminal, once medicalized and deemed “unstable,” always unstable.

Then, we get to a comparison. Comment #2 reveals a “secret” of their own (killing a set of plastic army men when 9 and never having told anyone), obviously poking fun at the matter and perhaps suggesting that we all have things in the past, tucked and locked away in Pandora’s box. This comment gets at the “so-what” of the matter – that is, to what extent should the weight of St. James’s past render his present reality and choices obsolete. Here, there’s no such thing as a murderer or plumber, just people who may or may not have murdered or plumbed.

Presented in the public commentary surrounding this case are conflicting social logics of identity and identification. The majority of them seem to treat the designation “criminal” as biological (here medicalized) and timeless. That is, once the details of St. James’ past are revealed, his current title as “University Professor” becomes obscured under the marker “murderer” for some and becomes for others, proof of his rehabilitation. St. James might argue that he has successfully rehabilitated and is no longer a “criminal” yet much public opinion seems to suggest otherwise. Thus, criminality is painted with a stroke of enduring timelessness and brings into focus whether such “debt to society” can ever really be paid off, ideologically speaking. In the public imagination, the labels “criminal” and “University Prof” are deployed as if representative of clear identity characteristics, rather than socially constructed tags that are assumed to say something about one’s ethics, morals, politics, and so forth. This confusion fails to see that these interpellations say little about St. James himself and more about the discursive processes whereby personalities, positionalities, sentiments and meaning become attached to the categories we call identity.

In Folk Devils and Moral Panics, sociologist Stanley Cohen suggests that moral panics is a condition and episode where exaggerated public opinion, aided by the media, doesn’t really point toward “real threats” to societal interests, but rather, manufactures what and who comes to be understood as dangerous, safe, criminal, etc. “Deviants” and “folk devils” (‘criminal’ by a bygone name) don’t exist as self-evident things, rather, they are constructed to assist in the portrayal of what is/isn’t normal, stable, and coherent (i.e., a university professor). In the same way the category “male” is constructed to give stability to what is understood as “female” and vice versa.

Perhaps “who” the professor “really is” is not the thing in question here. Might such negative public reaction to St. James’ past seem to suggest something of deception and identity? Some seem to suggest that the university was “duped” in not realizing who they were really hiring. In a Foucauldian manner, there’s a presumption that a “confession” or admission of his past crimes would take on an aspect of omniscience, as something that would have enabled “the truth” about his identity to be revealed from the start.

Isolating the “identity” of the other is never really for the other, per se, but rather for maintaining a certain kind of stability for the one doing the identifying. In James’s case, such a confession only allows those seeking the confession to slowly begin to see him as one thing (respectable: a university professor) and not another (deviant: an unchanging aspect attached to his criminalized past).