I was asked a question at a recent presentation I did up at the University of Chicago, concerning why the etymology of technical terms is a focus in an intro book that I wrote (and which I use in my own 100-level classes). Given my persistent critique of quests for origins it seems odd, or so the question might go, to focus on the origins of words, no?

I was asked a question at a recent presentation I did up at the University of Chicago, concerning why the etymology of technical terms is a focus in an intro book that I wrote (and which I use in my own 100-level classes). Given my persistent critique of quests for origins it seems odd, or so the question might go, to focus on the origins of words, no?

etymology (n.)

late 14c., ethimolegia “facts of the origin and development of a word,” from Old French etimologie, ethimologie (14c., Modern French étymologie), from Latin etymologia, from Greek etymologia “analysis of a word to find its true origin”

Good point. Why do I talk about etymologies in that book?

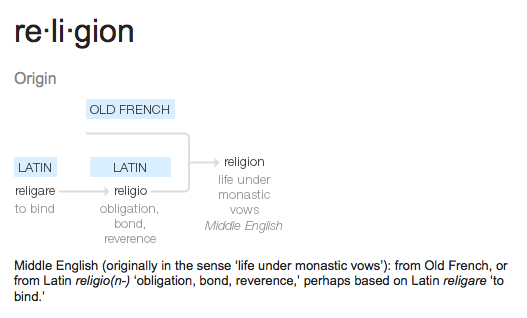

I bring this up in my intro class, in fact — when I’m wanting to keep my students’ eyes on something other than supposedly “true origins” whenever we talk about the various things that some word, like “religion,” have successively meant over the years. For unlike some, my interest in etymology is not linked to a quest to determine the proverbial source of the Nile — i.e., this is what something originally meant and thus that’s what it ought to mean for us today. Instead, I’m interested to introduce a dose of history — and by that I mean, variety, change, accident, and thus contingency — into my students’ sense of their own world and their place in it.

And with contingency I hope also to add a little agency.

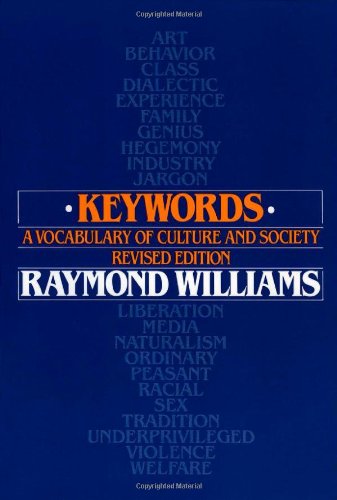

I tend to think this all has something to do with coming across Raymond Williams’s book long ago.

For many people seem to have difficulty re-imagining their situation as happenstance, as the way things happened to turn out but hardly the only way things could have been. And with this difficulty comes a form of acquiescence whereby they seem to willingly relinquish any ability they might have to influence the present — for the present is not seen as constituted by the doings of a variety of past actors who, like ourselves, had a variety of interests and a variety of domains within which they could have effect; instead, our present is experienced as an inevitable outcome that we just passively inhabit.

For many people seem to have difficulty re-imagining their situation as happenstance, as the way things happened to turn out but hardly the only way things could have been. And with this difficulty comes a form of acquiescence whereby they seem to willingly relinquish any ability they might have to influence the present — for the present is not seen as constituted by the doings of a variety of past actors who, like ourselves, had a variety of interests and a variety of domains within which they could have effect; instead, our present is experienced as an inevitable outcome that we just passively inhabit.

So the question is how can one begin to re-introduce agency and happenstance into a student’s understanding of the present — thereby historicizing their present, their world, and their normal?

And among the answers for me are etymologies.

For by demonstrating the variety of ways in which words have been used by others I hope to make possible a little curiosity about why we not only use some term as we do today but, more importantly, why we’re so confident that this is what the word ought to mean — after all, past actors were probably no less confident in their usage, in their worlds, even though it all seems to differ so dramatically from ours today.

And thus an added benefit is that we start to see language not as a neutral medium that conveys inner meanings but as itself being a historical phenomenon, a tool situated actors use and reuse, in various ways, to achieve various purposes.

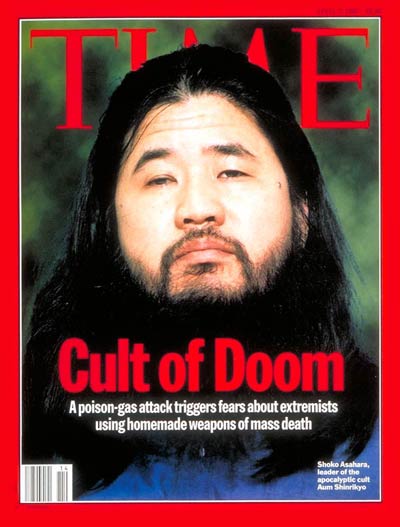

For now we can pose questions like: If the Latin-derived word “cult” hasn’t always been the stuff of sensationalist headlines then why is it that today? What do we gain by having that usage in our linguistic toolkit?

So, despite some using them as a way to determine a word’s true origin, etymologies, for me, accomplish pretty much the exact opposite: they allow us to do a thought experiment by imagining a comparative point, removed from us in time and place, that, when seen from where we are today, from how we use a word now, makes evident variety and change and thereby brings interested, situated, and competing language users back on stage — some of whom are in the very class where we talk about all this, of course. For, as I also try to persuade students, the subjects of study for any human science are, sooner or later, the very people doing the study, coz we’re people too and we use plenty of words to do plenty of things.

So, despite some using them as a way to determine a word’s true origin, etymologies, for me, accomplish pretty much the exact opposite: they allow us to do a thought experiment by imagining a comparative point, removed from us in time and place, that, when seen from where we are today, from how we use a word now, makes evident variety and change and thereby brings interested, situated, and competing language users back on stage — some of whom are in the very class where we talk about all this, of course. For, as I also try to persuade students, the subjects of study for any human science are, sooner or later, the very people doing the study, coz we’re people too and we use plenty of words to do plenty of things.

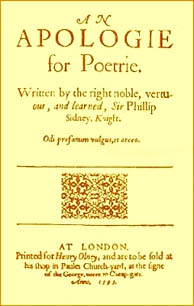

Etymologies in my class are therefore not a quest for origins but, rather, they’re one way to help make us a little more curious about the taken-for-granted; they present us with multiple, inconsistent, even contradictory taken-for-granteds. It’s a lot to bite off in a 100-level course, perhaps, but the sometimes destabilizing variety that a well placed etymology introduces — “Did you know that “an apology” once meant a rigorous defense of your position and not, as it does for us today, an expression of regret for holding it?” — inserts a little wedge into the now unquestioned commonplace, one that helps to make us curious about how it all got to be so common when it’s anything but.

I am in wonder of Leslie’s ability to sleuth out some of the the meanings of life, and how we may or or may not use our agency to cause changes in our lives. I became interested in etymology years ago when an etymologist/poet, named John Ciaridi, was on the NPR every week. He provided us fascinating info on idioms, words and phrases. I have a copy of his book, published in 1987 by his family after his untimely death. “Good Words to You” is its title. I would recommend it to anyone who enjoys etymology. Both he and Leslie are Wordsmith’s.