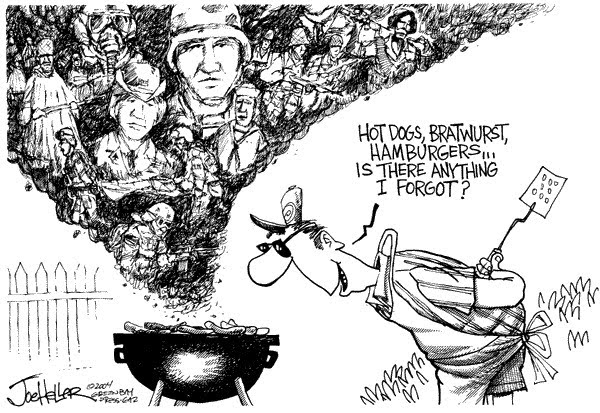

Today is Memorial Day in the U.S. — a federal holiday marking a time to remember the past sacrifices of members of the armed forces.

Today is Memorial Day in the U.S. — a federal holiday marking a time to remember the past sacrifices of members of the armed forces.

In many cases, of course, “sacrifice” is a euphemism for death.

But it’s also a day that marks blockbuster sales — “half-off tops and shorts!”

The curious thing is that the two different meanings that Memorial Day signifies are seen as contradictions by some, as if there is a purer, more noble significance at its root, one that is not just missed by all the retail hoopla but actually polluted and perverted by stores jumping on the holiday sale bandwagon. But it’s this seemingly more noble form of nationalism that catches my attention, for it strikes me as oddly more conservative than the holiday sale version of Memorial Day that we, here in the U.S., all know through commercials and newspaper ads.

For, if you think about it, there’s a pretty firm link between military action (another euphemism, for going to war and, let’s be frank, killing lots of people on all sides) and the rhetoric of “our way of life.” That’s what the terrorists hate about us, we were told soon after the attacks on September 11, 2001; that’s what was at stake and that’s what members of the military — who used to fight for their “gal back home” — are now apparently fighting for.

For, if you think about it, there’s a pretty firm link between military action (another euphemism, for going to war and, let’s be frank, killing lots of people on all sides) and the rhetoric of “our way of life.” That’s what the terrorists hate about us, we were told soon after the attacks on September 11, 2001; that’s what was at stake and that’s what members of the military — who used to fight for their “gal back home” — are now apparently fighting for.

Now, I’m not sure what “our way of life” (yet another euphemism, of course) is supposed to signify, at least when politicians use the phrase; and, to be honest, I’m not sure who else talks all that much about it other than politicians. I suspect that for some it refers to what America looked like in the 1950s or ’60s, at least in some contemporary imaginations. Lots of white picket fences probably populate that image, along with a variety of “modern day conveniences” — that is, there’s probably a nostalgia loaded into that phrase, one that perpetuates a very particular idea of the nation, an idea surely packed with class and race and gender and regional significance.

But for me, when I think of “our way of life,” I tend to think not of some idyllic past, an idealized notion of the group, or even some abstract idea like freedom (another semantically potent euphemism…), but, instead, of how we each, in the present and in some coordinated manner (it is a plural pronoun, after all — “our way of life”) participate in reproducing the conditions of the material taken-for-granteds that constitute social life for many. And, thinking that, it’s clear to me that the collection of activities that we usually group together as “the economy” is pretty near the top of the list; for labor, class relations, and systems of valuation and exchange provide the means by which we put roofs over our heads and food in our stomachs.

But for me, when I think of “our way of life,” I tend to think not of some idyllic past, an idealized notion of the group, or even some abstract idea like freedom (another semantically potent euphemism…), but, instead, of how we each, in the present and in some coordinated manner (it is a plural pronoun, after all — “our way of life”) participate in reproducing the conditions of the material taken-for-granteds that constitute social life for many. And, thinking that, it’s clear to me that the collection of activities that we usually group together as “the economy” is pretty near the top of the list; for labor, class relations, and systems of valuation and exchange provide the means by which we put roofs over our heads and food in our stomachs.

So “our way of life” is, for me at least, intimately linked to buying and selling; in fact, I recall President George W. Bush telling us as much in the immediate aftermath of the 9-11 attacks, when — in a speech that very night, one that opened with “Today, our fellow citizens, our way of life, our very freedom came under attack…” — he made specific mention of the economy (click the following quotes to read the full transcripts for each), assuring his no doubt worried, maybe even panicked, listeners that:

Then, in a speech on September 20, 2001, he made the following request (with the intended audience all along surely being both domestic and foreign listeners):

Then, in a speech on September 20, 2001, he made the following request (with the intended audience all along surely being both domestic and foreign listeners):

And, a few weeks later, on the one month anniversary of the attacks, we heard the following from him at a press conference:

And, a few weeks later, on the one month anniversary of the attacks, we heard the following from him at a press conference:

Or consider another press conference, four years later, in December 2006, when advance rumblings were being felt of what eventually became a collapse of the U.S. (and global) economy — when, if you recall, credit stopped flowing, major banks collapsed, and people quite literally stopped buying and selling. We heard the following remarks then:

Or consider another press conference, four years later, in December 2006, when advance rumblings were being felt of what eventually became a collapse of the U.S. (and global) economy — when, if you recall, credit stopped flowing, major banks collapsed, and people quite literally stopped buying and selling. We heard the following remarks then:

My interest here, however, is not to criticize the previous administration (as so many did after hearing Bush’s plea for people to go shopping); it is also not to support or criticize the way so many of us live our daily lives or the things that we expect or take for granted. Instead, it is simply to make explicit the link — like it or not — between that part of social life that we call the economy and the assumed, daily conditions in which we all think and act.

And then to ask: How far one would go to ensure that those conditions — our way of life, i.e., how we feed and clothe our families, how we pay for vacations and high speed internet — are not changed or undermined?

What price is worth paying for your idea of normalcy?

For it seems to me that those who criticize the crass commercialization of holidays like Memorial Day (animated, it seems, by a nostalgic origins somewhat akin to that which we also see in the “Put Christ Back in Christmas” movement, perhaps?), those who imagine a more pristine, dare I say authentic, set of values that, instead, ought to be commemorated on that day, fail to entertain how the “half-off” sales may indeed be the lifeblood of this social experiment that we call the nation. For that’s how your neighbors — who more than likely live very close to the financial edge, like us all, carrying lots of debt, and with very little cash flow — pay their mortgages, their car loans, and how you may very well buy your own food.

The successful reproduction of “our way of life” may therefore depend on those sales periodically injecting a little juice into that zero sum game that we call the economy.

One could argue, then, that failing to entertain this link between the material and the ideal — whether by one wanting to mark a more solemn day of deeper meaning or by someone simply concerned with getting a good deal on some new summer shorts to wear to the Memorial Day weekend bbq — is exactly what all that fighting and dying was all about.

The right to forget and to go about our business as usual.

Now, whether anyone’s “way of life” ought to be considered worth fighting, killing, and dying for is, of course, another question entirely…