To open the Introduction to my 2003 collection of essays, The Discipline of Religion — a book concerned with, among other things, investigating the links between the invention of and social uses for privacy, on the one hand, and, on the other, the practical, governing role played by the discourse on belief, experience, or faith — I wrote as follows:

To open the Introduction to my 2003 collection of essays, The Discipline of Religion — a book concerned with, among other things, investigating the links between the invention of and social uses for privacy, on the one hand, and, on the other, the practical, governing role played by the discourse on belief, experience, or faith — I wrote as follows:

it is 1988 and I’m at home, living just outside Toronto, watching a television special on the Olympic torch relay across Canada to Calgary, the host of that year’s winter Olympic Games. I recall seeing a young boy, lucky enough to be selected to carry the torch for his designated distance, running through the crowded street with the torch held out over his head, obviously excited. His father runs alongside with his video camera, matching his son’s pace, documenting the event for posterity. The boy looks at his father, and into the camera, and says, “I can’t wait to get home and see this on TV. ” I recall thinking to myself, “You’re living it now, kid, so why do you have to get home to see it on television?”

This is likely one of the first memories I think I have of an occasion when the intertwined nature of the past, present, and future became apparent to me, i.e., when the present’s continual invention of itself was obvious, via its contrived distance from an imagined past that is no longer here or a hoped for future that has yet to appear.

It was the moment, as I later went on to write in that Introduction, when we use a

technique for creating significance by means of a remembered past in an anticipated future: “Just wait until I tell somebody about this!”

It was only then that I started to think about how the seeming evidency of a situation becomes sensible, bounded, framed and ordered only by our displacing of it, our juxta-positioning of it, in relation to positions that we imagine to be elsewhere, providing us with a privileged vantage point from which we can then look back onto the now, to see it by seeing what or where it is not, by placing it into an forced relation to other things, to find what we think of as patterns so that we now know what to pay attention to and what to ignore.

For otherwise the present is a hectic, endless, centerless place.

It would seem, then, that only by abandoning it, by racing away from it, can one ever really be in the moment.

“I can’t wait to get home and see this on TV. ”

It’s much the same as snapping a selfie, I think, whereby we imagine how we are seen by others…, when, all along, the view of ourselves from elsewhere is a fabrication of our own extended arms. Though apparently viewed from afar, it turns out that we never left our perch. For we inspect the picture, decide if it does or doesn’t do us justice, scrutinize its composition, and, if not satisfied, we trash it and extend the camera again, to take another, and then another…, producing the illusion of distance, objectivity, perspective, subjectivity, when, all along, the photo could not be more intimately linked to who we, in the here and now, wish to see ourselves to be, making the selfie far from how any others might see our selves.

With the recent death of Leonard Nimoy much in the press — aka, Mr. Spock — I’ve been thinking a little about this again; for, when seen today, the original Star Trek series could not have looked any more like the mid- to late-1960s, when it was filmed. Watching it now is like watching an old episode of Laugh-In — the hair, the colors, the styles, the language, the social concerns…

But how can we help but reproduce the sensibilities of the present in our pictures of the past or the future, for whether or not we preface our words with “In the beginning…” or “Once upon a time…” they’re still our words; the tale teller, no matter how crafty or gifted, never leaves the situation of the telling — much like a how past World’s Fairs always tried to give people a glimpse of the future, a sneak-peak that we today, who are well beyond those past people’s imagined tomorrow, can’t help but see as anything but archaic.

But how can we help but reproduce the sensibilities of the present in our pictures of the past or the future, for whether or not we preface our words with “In the beginning…” or “Once upon a time…” they’re still our words; the tale teller, no matter how crafty or gifted, never leaves the situation of the telling — much like a how past World’s Fairs always tried to give people a glimpse of the future, a sneak-peak that we today, who are well beyond those past people’s imagined tomorrow, can’t help but see as anything but archaic.

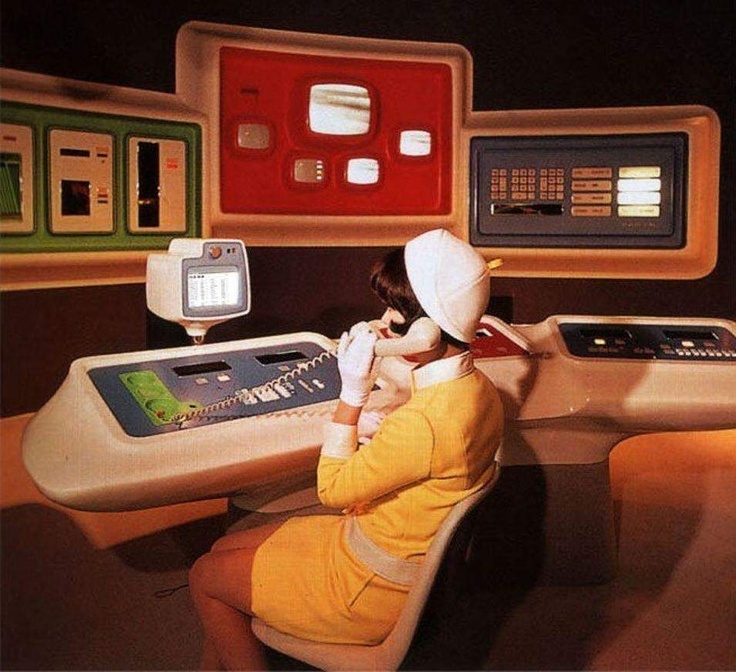

This colorful office of the future, from the 1964 New York World’s Fair, just looks like 1964, looks like an antiquated Star Trek set, in fact, no matter how hard they may have tried to erase their dated presumptions, what amounts to their selfie’s extended arms.

The phone has a cord.

‘Nuff said?

But what’s most curious of all, perhaps, is that I’m today discussing what a 2003 book was about, which in turn narrates a memory I then recorded (do I still recall it or do I only remember writing about it then?) of watching TV back in 1988 (almost 30 years ago!), all of which is taking place here in WordPress as I sit and write and imagine this to be posted in public tomorrow and then read by you who knows when.

So…, hello future; do you have rocket shoes yet?

I have recently read a study on the historicality of the narrative of the Gospel of John in which, inter alia, the author took issue with the so-called double layeredness of the Gospel according to which ‘John,’ in shaping his account the way he does, actually recounts his own situation in a localisation and time at a distance from the history he references. It strikes me how your argument here is another counterargument to the critique leveled at critical gospel studies coming from the side of that branch of gospel scholarship that insists on the essential historical trustworthiness of the gospel accounts as memory resources for an accurately memorialized figure of Jesus of Nazareth. While I share your viewpoint, and have pursued a similar kind of reading of early Christian literature, I also see that the big issue is not whether the gospels are instances of accurate memorialization (that is a subordinate issue, I think) but rather, why is there now this insistence on accurate memory? Why now this insistence on the basically unbroken continuity between the ‘historical’ life of Jesus of Nazareth and (certain understandings of) Christian belief/discourse today? The recent rise of ISIS with its own claims to authenticity, and Western reactions to it, set alongside evangelical gospel scholarship, illustrates the big hidden issue operating in both these kinds of uses and constructions of the past, namely the drawing of boundaries in aid of social definition and action.

“[W]hy is there now this insistence on accurate memory?”–excellent point. This very way of approaching the past is itself a product of a specific historical situation.