Once upon a time, in a land far away, and while walking around the book display at our field’s main national conference here in North America, I was chit-chatting with the editor of a major press in my field — a place at which I’d not yet published.

Once upon a time, in a land far away, and while walking around the book display at our field’s main national conference here in North America, I was chit-chatting with the editor of a major press in my field — a place at which I’d not yet published.

A question was posed to me that went something like this:

So, tell me: why do you publish at a place like Equinox?

There was a lot embedded in that question, I think. For, compared to the place where this person worked, Equinox was a much smaller player with far less prestige — why would such a publisher matter to me?

This editor was on the clock, doing fieldwork. It’s a business, after all.

Choosing not to address what I took to be a good dose of condescension not far from the surface of that question, I answered by saying something about how much I appreciated its willingness to take risks and also my sense of loyalty to a publisher who took a risk on me early on in my career — something that my interlocutor appreciated hearing.

After all, what editor doesn’t like loyal authors who return with new projects?

But my answer likely wasn’t satisfactory, for the punchline to the conversation was about why I wasn’t submitting anything to that person’s press.

For, to fine tune my earlier comment, editors like their own loyal authors almost as much as they like authors disloyal to other editors. Like I said, it’s a business after all.

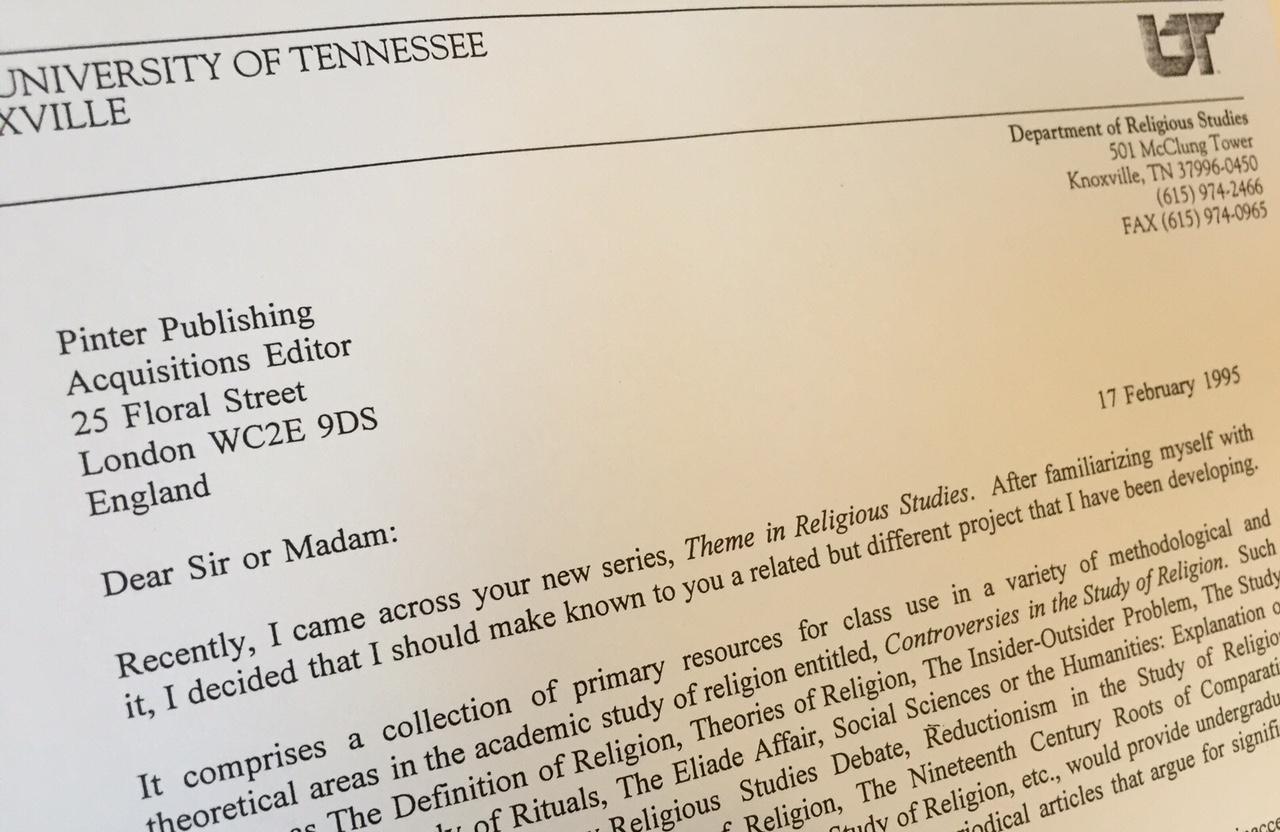

Since then I did submit and I’ve had three separate projects rejected by that press. At the time of our conversation, I don’t think the editor remembered having already rejected my first book (a revision of my dissertation), a prospectus for which went to that publisher among many others, back in 1995.

I still have the rejection letter.

So that’s four rejections from that one publisher. And three of those projects eventually appeared elsewhere (one with Equinox, in fact).

(Aside: I sometimes wonder if early career people realize that, while there certainly are perks that come with seniority, for some of us, at least, the rejections of our work never stop coming.)

I can take a hint; I don’t plan on submitting again to that press.

Now, I’ve been extremely lucky to have my work appear in a variety of venues over the years, published on both sides of the Atlantic. My first book appeared with a major international press and, for all I know, the happenstance of who contracts whom played a significant role in the book even finding readers. For while authors probably like to think that the sheer force of their arguments wins the day and creates the audience, the influence of their work may (sometimes? often? always?) have far more to do with such things as the distribution network of their publishers and how widely their catalogs are mailed or maybe even how confident book review editors are in actually receiving a copy of the volume from the press.

Thinking back on my own writing career, I admit that, despite the unpredictable contingency of it all, I tried to be pretty intentional about what I did — trying to grab whatever agency I thought I had in all this. So of course I sent the prospectus to my first book, not long after defending it as a dissertation, to about 15 publishers on my wishlist; I had only one ask to see the full manuscript and one publisher rejected it twice (I’ve talked about this process elsewhere). But, luckily, that one publisher contracted it, giving me a CV line that others in the field seemed to value. (I speculate it played a significant role in my first tenure-track job, in fact.) I was an Instructor, back then, at the University of Tennessee, and pretty pleased to have a contract in-hand while on the job market. While much in the field frustrated me back then (well, not just back then, if I’m being honest) I also had a fair bit of energy and time to focus on writing. So, with my first book contract signed, in mid-1995, and the revisions happening quickly (I sent the completed ms. to the press later in 1995, though it didn’t come out until 1997), I began writing other essays and thinking of other projects. And I remember seeing a collection of anthologies, designed for the classroom, on the shelf in Rosalind Hackett‘s office, published by a little press from the UK called Pinter. I had ideas of my own for a classroom anthology series, on controversies in our field (like theology v. religious studies or the definition of religion — an idea I’d talked with Don Wiebe about while a grad student in Toronto, and he’d shown me similar sorts of series in Philosophy); so, fresh from defending my dissertation in January, I wrote the press.

And that’s how I ended up meeting Janet Joyce, who was then working at Pinter — the person who eventually founded Equinox some years later — with whom I’ve had a variety of projects over the years.

And that’s how I ended up meeting Janet Joyce, who was then working at Pinter — the person who eventually founded Equinox some years later — with whom I’ve had a variety of projects over the years.

But then, as I recall, Pinter got bought up by Cassell and Cassell was then bought up by Continuum, and they in turn were eventually bought up by Bloomsbury during its buying spree just a few years ago…. So my working relationship with Janet moved places over the years. I still went to other presses with my work (I’ve now published books at, I don’t know, 5 or 6 different presses, some in the US some in Europe) but all along I’ve regularly worked on a variety of projects with Janet — e.g., monographs, book series, edited books — and whomever it was that she worked for at the time. So when she set out on her own, and founded Equinox, there was a pretty strong incentive to move projects with her.

And now Culture on the Edge has not one but two book series with Equinox and two volumes are now out.

But why Equinox? — that was that editor’s question.

Apart from a good working relationship and a sense not only that she dealt straight with me but also that she trusted my judgements (Aside: some publishers seem to cultivate an adversarial relationship with authors, since they’re the gatekeepers…, yet we provide all the content, so why not a more collaborative approach?), it was because she understood that, though small, the group of people working in non-traditional ways in the field (i.e., naturalistic scholars, non-theological scholars influenced by postmodernism, etc.) were worth taking a risk on. She didn’t always say yes to my hair-brained schemes, of course, but she said yes often enough, and quickly enough (i.e., she has good business sense and knows what she likes — or what the field will respond to in any number of ways), and without the need of consulting what, as an author interested in seeing the field change a bit, I find to be a rather cumbersome and highly conservative bureaucratic apparatus that (sometimes? often? always?) moderates other editors’ decisions. For some presses not only have the requisite peer review processes but layers of oversight committees that need to give the thumbs up before a project is contracted.

So yes, Equinox was a small press that lacked some of the pluses that we associate with the big presses, but I was dealing directly with the owner who seemed to trust my judgments and moved quickly when it mattered.

And that’s worth more than you think — especially when contracting and publishing a ms. can sometimes take years to see through the process. And that’s when everything works well!

I continue to send projects to a variety of presses, of course — e.g., in the past three or four years my work has appeared at three different publishers, In fact, I have two projects in front of an editor elsewhere right now, and, as noted earlier, a third project was recently rejected by the one mentioned above. But that little, independently-owned UK publisher remains a press with which I enjoy working; in fact, I can’t begin counting all the people now working in the field whose scholarship has appeared there in one venue or another — writings that, in a number of cases, somehow intersected with projects with which I was involved, either formally or informally. And so, as someone interested in changing the field, however much I’m able, given whatever agency I actually have — which, in part, means getting new voices into print and into the conversation — I’ve found that to be worth far more than the imprimatur that some presses think they can bestow upon the lucky author.

All of which brings me to my most recent little, edited volume with Equinox, Fabricating Origins — it stands out for me because it not only grew from a series of posts on this very blog but because half of the contributors invited to write for the book (those providing much of the volume’s new material) did not yet have their Ph.D. degrees at the time of writing their chapter. That’s right: they were all doctoral students, not all even at the ABD rank. The job market dances to its own drum, of course, but my hope is that these contributors all eventually join the field for the long haul, since they’re all interesting, creative thinkers who bring something new and something we need. (Did I mention that I first met most of them when they friended me on Facebook, after reading me in class?)

That not every press would say yes when it heard who I wanted all of these contributors to be is the point I hope you see me to be making here — a point that that editor, with whom I talked and walked so long ago, might have had trouble grasping if I’d really said why I went to a press like Equinox. For given what I sometimes see coming out from some other presses, they’re often engaged in the business not of changing the field but of working very hard to keep it the same.