One of the premises of Culture on the Edge is that an implicit, untheorized norm is still presupposed, and its legitimacy is thereby reproduced rather than being historicized, despite many scholars’ recent efforts to develop what they see to be more nuanced, historically sensitive, and situationally specific approaches to identity studies. For it is not uncommon to find seemingly anti-essentialist scholars now studying various identities in terms of their hybridity, seeing them as creoles, studying how diaspora movements have traveled and changed, and documenting the complexity of syncretism–developments understood as important improvements on what are now seen to be previous generations’ far too simplistic studies of social life. After all, as important a an early sociologist as Emile Durkheim seems merely to have understood “society” to be a homogenous, undifferentiated unit.

But these now preferred terms–hybridity, diaspora, creole, syncretism–are the tips of no less troublesome icebergs inasmuch as their use presupposes an unexamined origin and thus norm against which the resulting moving mix can be judged as a mix (i.e., because that is pure then this is blended), as having moved (i.e., moved from where? From the homeland, of course), and thus as the result of prior, stable, original components. But sadly, those supposed sources are themselves generally not also understood as the inevitably blended results of yet even more primordial elements which, yes, are themselves the blended results of… Well, you get the idea, for surely someone else was there before some people became a “we” and made some place “our” homeland, no?

Freezing the continual change of that limitless archive we simplify by calling it history, and doing so for our analytic purposes, is perfectly fine, of course–in fact, its necessary if we’re going to talk about anything as a discrete thing that can be talked about. “For my purposes, I shall consider American culture to be….” is a perfectly respectable scholarly move, to stipulate one’s starting point for ones own intellectual purposes, since we can’t talk about everything all at once, can we? But when I read scholars writing about, say, early Christianity being a syncretistic movement (all in an effort, of course, to complicate anti-historical narratives of how it was an utterly unique phenomenon that just spring on the stage of human history of its own accord) it seems taken for granted that the things considered to be its prior components, from which it borrowed–say, Judaism and Greco-Roman culture–were themselves already firmly in place, much like two distinct billiard balls colliding and producing a sound. Thus the effort to destabilize the origins tale we tell about one social formation (i.e., early Christianity) is premised on stabilizing two others.

But do a little digging and it won’t be difficult to see that the billiard balls themselves were hardly solid objects, for they were not just internally diverse (the tricky compound “Greco-Roman” should have already told us as much) but, perhaps, this or that ancient material’s delimitation as Jewish or as Greco-Roman is a modern effect, boundaries read backward in time based on what one today thinks of as rightly Jewish, as properly Greek, as legitimately Roman. While we may have no choice but to do this we can choose to recognize it is us who’s doing it.

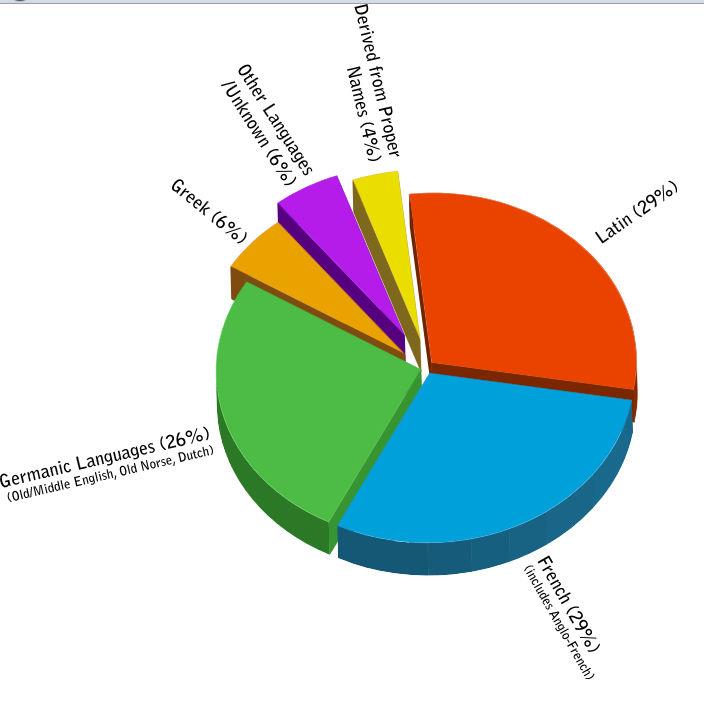

Case in point: generally many of us would never refer to English as a creole, since creole languages–as everyone knows–are those of “other” peoples, marginal peoples, those that developed from pidgins–languages of necessity between different peoples who find themselves in need of communicating. It’s with just such an understanding in mind that the editors of The Creolization Reader are able to know that “[t]here are about 84 recognized creole languages worldwide” (5). English, instead, is among the sources often drawn upon by others who develop their own creoles, right? (This position makes sense, of course, given how the British spread their language, along with their navy and their political/economic system, worldwide.) But a simple visit to Wikipedia’s page for Foreign Language Influence on English makes evident that its rather illusory to think of English as some sort of unified thing when we consider its derivation (its many current dialects make its modern diversity profoundly apparent as well–how do you pronounce “been“?).

But the very title of that Wikipedia page–Foreign Language Influence on English–makes the problem evident: only if we essentialize the language and take modern English (but which one?!) as the necessary, virtually Hegelian outcome of historical processes would we talk of how things that existed prior to it “influenced it,” instead of concluding that what we today refer to as the English language (the subject of that third person pronoun “it” that was apparently busy borrowing from its neighbors) “resulted from” these earlier linguistic systems. But in phrasing it as Wikipedia does–not dissimilar to how I above too casually referred to early Christianity as if it was an already existing subject that “borrowed” from other linguistic objects of its time, as if it was already there at its own origin–in presuming that one would never refer to English itself as a creole language of practical necessity that arose, like any other, from a complex blending and mixing (some intentional and some accidental) from prior sources that were themselves the results of yet more blends (some intentional and some accidental) from even earlier sources, we nicely normalize the known and the familiar that some of us now take for granted, thereby employing it as a standard against which to judge the deviance, change, or marginality of other so-called derivative systems.

But the very title of that Wikipedia page–Foreign Language Influence on English–makes the problem evident: only if we essentialize the language and take modern English (but which one?!) as the necessary, virtually Hegelian outcome of historical processes would we talk of how things that existed prior to it “influenced it,” instead of concluding that what we today refer to as the English language (the subject of that third person pronoun “it” that was apparently busy borrowing from its neighbors) “resulted from” these earlier linguistic systems. But in phrasing it as Wikipedia does–not dissimilar to how I above too casually referred to early Christianity as if it was an already existing subject that “borrowed” from other linguistic objects of its time, as if it was already there at its own origin–in presuming that one would never refer to English itself as a creole language of practical necessity that arose, like any other, from a complex blending and mixing (some intentional and some accidental) from prior sources that were themselves the results of yet more blends (some intentional and some accidental) from even earlier sources, we nicely normalize the known and the familiar that some of us now take for granted, thereby employing it as a standard against which to judge the deviance, change, or marginality of other so-called derivative systems.

Simply put, what does qualifying a language as creole accomplish, other than normalizing those mixes that we wish to represent as pure and timeless? For “creole language,” let alone “syncretistic culture,” strikes me as utterly redundant. Thus there are rather more than 84 creole languages worldwide, no?

Light years (and surely some very different politics) seem to span someone talking today about cultural hybridity and creolization, on the one hand, and, on the other, someone else preferring “the proper Queen’s English” to all others. But I’m not so sure they’re all that different.