The persecution of Ahmadis has hit the news again with the killing of an American Ahmadi doctor in Pakistan last week while he was volunteering in an Ahmadi hospital. Having written on the issues of labels in relation to the Ahmadi before at the Bulletin for the Study of Religion blog, I found the careful phrasing of the Reuters article about the shooting of the doctor impressive. Describing the Ahmadi as “a group that says it is Muslim but whose religion is rejected by the state,” I appreciated the precision with which the author acknowledged who described the Ahmadi as Muslim and who rejected that label. This phrasing is similar to what I have advocated generally. To acknowledge that labels are both contested and consequential by stating with precision who applies and contests particular labels is imperative.

The persecution of Ahmadis has hit the news again with the killing of an American Ahmadi doctor in Pakistan last week while he was volunteering in an Ahmadi hospital. Having written on the issues of labels in relation to the Ahmadi before at the Bulletin for the Study of Religion blog, I found the careful phrasing of the Reuters article about the shooting of the doctor impressive. Describing the Ahmadi as “a group that says it is Muslim but whose religion is rejected by the state,” I appreciated the precision with which the author acknowledged who described the Ahmadi as Muslim and who rejected that label. This phrasing is similar to what I have advocated generally. To acknowledge that labels are both contested and consequential by stating with precision who applies and contests particular labels is imperative.

Unfortunately, that precision, both for Reuters and Katherine Houreld, the particular journalist credited as the author, appears to apply only to marginal groups like the Ahmadi. Houreld, for example, uses very similar language (with further details) when describing a different case of Ahmadi persecution, “He is also an Ahmadi, a sect that consider themselves Muslim but believe in a prophet after Mohammed [Mirza Ghulam Ahmad]. A 1984 Pakistani law declared them non-Muslims, and Ahmadis can be jailed for three years for posing as a Muslim or outraging Muslims’ feelings.” In contrast, she does not qualify the identifications of people labeled Muslims and Christians in Pakistan when discussing the persecution of “minorities in Pakistan” generally. In this account, she identifies Sufis and Shi’ite Muslims without qualification, even though some in Pakistan question their Muslim identification. Similarly, other Reuters articles that reference Sunni and Shi’a groups, such as an account of recent Shi’a unrest in Saudi Arabia, also avoid any qualification of their identification as Muslims.

This qualification of Ahmadi claims to a Muslim identification, while reflecting the precision that I have advocated, serves to further marginalize them. Those commonly identified as orthodox Muslims do not receive similar treatment (even though who is orthodox is contested) because broader public discourse generally accepts their identification (despite internal disputes among those who identify as Muslims). In the midst of reporting on the persecution and constructing a sympathetic narrative of the plight of this minority community, the marginalizing, unbalanced treatment reinforces and supports implicitly the position of their critics, the persecutors, who claim that the Ahmadi are not truly Muslim. As the article highlights, contestation over religious identifications has significant consequences legally and socially, something that I do not get the impression that Houreld or Reuters intend to support.

So, what can people do to avoid taking sides in these contests over identifications? Recognizing that all identifications are strategic, context-specific, and contested is a first step. The harder step (something that I do not always complete successfully) is to acknowledge who is applying each label when we reference labels such as religious identifications that carry significant social and legal implications. Referencing whose definition determines that those who identify as Sunnis can be labeled Muslim reminds all of us that all such labels, even when commonly accepted, are neither pre-determined nor beyond questioning, and it avoids supporting one side against another or further marginalizing minority groups.

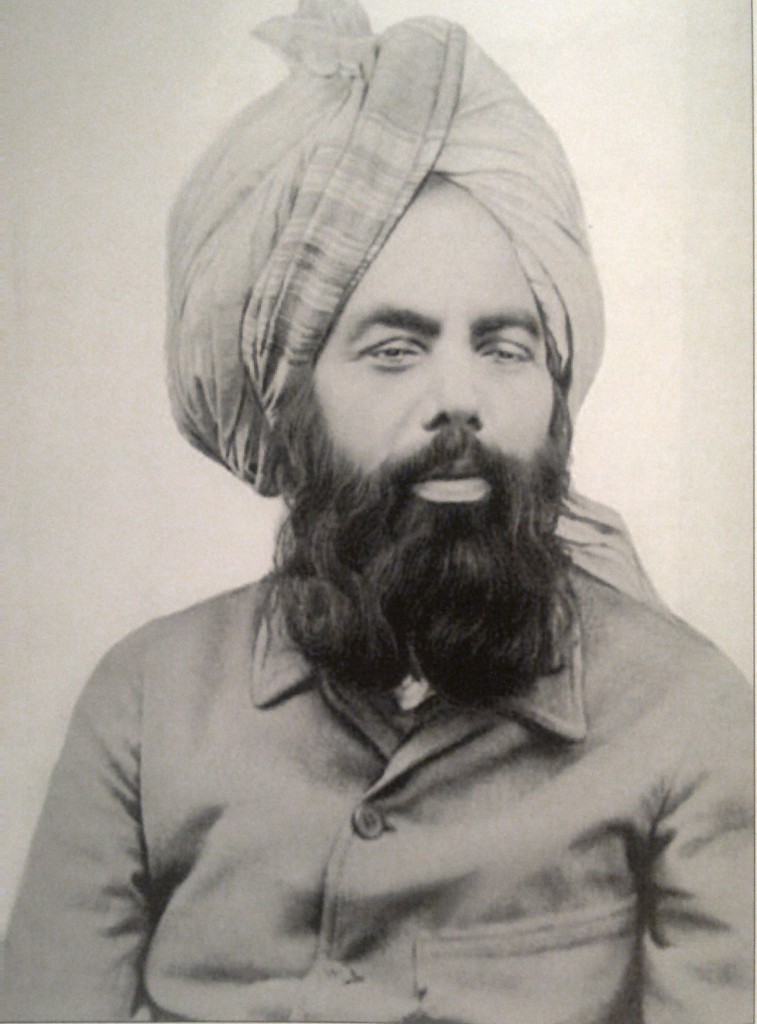

Photo of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad in the public domain