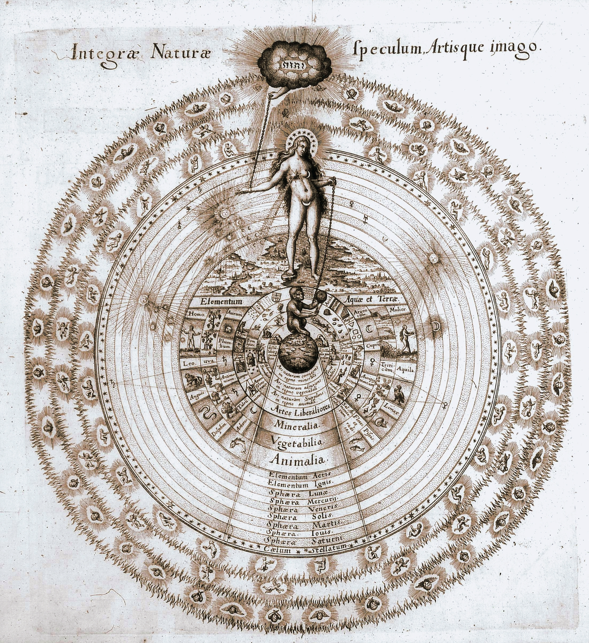

Lots of scholars of religion are focused these days on studying such things as implicit religion, the Nones, or almost any other so-called worldview that people might be said to work with or inhabit (e.g., many are hot on the trail of secularism). What I find interesting about all this is the way in which a professional identity is being recreated, by those who work in this field, in the face of twenty year’s worth of critiques of the category religion itself (pretty obviously the field’s primary organizing concept); for it seems that the more the term is criticized (as being a Latin-based signifier that was exported in the age of colonial contact, making it hardly the universal designator that it was once thought to be — see here for a good primer on this argument) the more data these scholars seem to have to study. Consider the so-called Nones — those who answer a few questions on a survey, about belief in God or attendance at church, and who are now thought by many to comprise a cohesive social, political force: scholars of religion are intent on studying them despite their adamant denial that they’re religious. What’s curious is that while many such scholars criticize those of peers who fail to take the insider’s viewpoint seriously, as they might say, yet here, in the case of the Nones, people’s refusal to identify as religious is hardly a barrier to eager scholars of religion. Continue reading “The Sun Never Sets on the Study of Religion”

Lots of scholars of religion are focused these days on studying such things as implicit religion, the Nones, or almost any other so-called worldview that people might be said to work with or inhabit (e.g., many are hot on the trail of secularism). What I find interesting about all this is the way in which a professional identity is being recreated, by those who work in this field, in the face of twenty year’s worth of critiques of the category religion itself (pretty obviously the field’s primary organizing concept); for it seems that the more the term is criticized (as being a Latin-based signifier that was exported in the age of colonial contact, making it hardly the universal designator that it was once thought to be — see here for a good primer on this argument) the more data these scholars seem to have to study. Consider the so-called Nones — those who answer a few questions on a survey, about belief in God or attendance at church, and who are now thought by many to comprise a cohesive social, political force: scholars of religion are intent on studying them despite their adamant denial that they’re religious. What’s curious is that while many such scholars criticize those of peers who fail to take the insider’s viewpoint seriously, as they might say, yet here, in the case of the Nones, people’s refusal to identify as religious is hardly a barrier to eager scholars of religion. Continue reading “The Sun Never Sets on the Study of Religion”

They’re Just Old Buildings, Right?

Prompted by the discussion surrounding Rachel Dolezal’s NAACP resignation, this series of posts is about how and when we take performativity seriously…, and when it bows to interests in historical or experiential specificity.

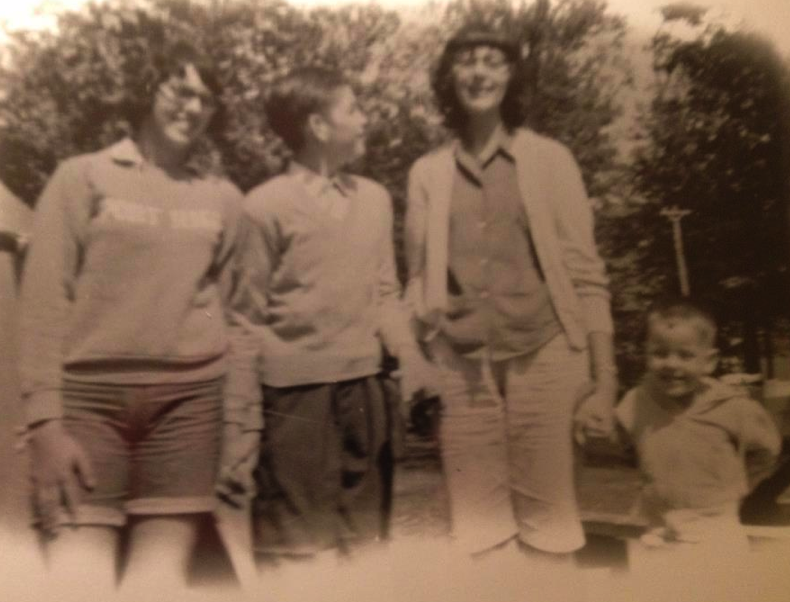

My brother, Elliot, who died in 1996, was mentally disabled. That’s him above, with my two sisters. And that’s me on the far right; he was 12 years older than me and, as a baby, had taken a particularly bad fall from his highchair; presumably, that’s what caused what, just a couple years later, became painfully apparent to my parents: he had no speech development and began suffering from repeated grand mal seizures. I won’t belabor the tragedy of his life and death, but suffice it to say that in the 1950s there was little choice but to institutionalize him, when he was a young boy, in a government-run institution. So his profound cognitive problems were quickly compounded by a number of physical problems — who knows what all abuse he was subjected to over the course of his life, but from the “cauliflower ears” and missing teeth that soon resulted, well…, it was apparent that life in the institution was horrendous. Continue reading “They’re Just Old Buildings, Right?”

Social Media Is Out of (Your) Control, So Is Life

Liking a post and favoriting a tweet serve as excellent examples of the complexity of life that is out of our control in ways that we often don’t realize. The meaning of liking, favoriting, etc., clearly shifts depending on the context. Sometimes clicking the star or thumbs up literally means that I like something; sometimes I want to say that I hear you, acknowledging someone’s comment or post. This varied meaning is true throughout language. Words and symbols have a range of meanings that also can shift radically over time and place (a computer used to mean “one who computes;” a Swastika is a positive symbol in multiple cultures today). That simple click (like other forms of communication) has other complexities, too, that illustrate the lack of control that any of us have.

Continue reading “Social Media Is Out of (Your) Control, So Is Life”

Words We Choose From a List

In honor of Don Draper’s departure from our TV screens last night I thought I’d share a piece of advertising that makes evident that it’s not the words you use but how you say them. Continue reading “Words We Choose From a List”

In honor of Don Draper’s departure from our TV screens last night I thought I’d share a piece of advertising that makes evident that it’s not the words you use but how you say them. Continue reading “Words We Choose From a List”

About That Knife

Recently, I had a student come by during my office hours. Upon entering, one of the first things he said was something like “Whoa, Dr. Smith – I wouldn’t have thought that you’d have a knife!”

To be honest, I wasn’t exactly sure what he was talking about. Then I remembered that I have an old knife hanging in a shadowbox frame on my office wall that I use as an art piece (it’s got some very interesting markings). Frankly, I’d never made much of it, except that it didn’t make the aesthetic cut at my house. In the hierarchy of interior design to which I ascribe, that means that my office became its new home. Continue reading “About That Knife”

What Did You Mean?

What makes something offensive? In the contemporary context, some attempt to censor (often through social media campaigns) presentations that they consider offensive, making that label particularly useful for restricting public discourse. Two stories from December highlight the complexity of labeling something offensive.

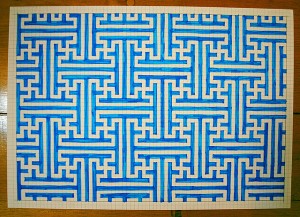

A shopper in California during the holiday season noticed that wrapping paper in the Hanukkah section of a store had swastikas incorporated into the design. Deeply troubled by this symbol that the shopper associated (for obvious reasons) with Nazism, she reported it to the manager. With the story reaching the media, the store removed the wrapping paper with the offensive design nationwide and began an investigation into how the design was created and approved. Continue reading “What Did You Mean?”

The Problem with Phallic Play-Doh

In yet another example of how categorization matters, consider the latest controversy in children’s playthings: Hasbro Corp., maker of the famous Play-Doh brand modeling clay, recently released a Play-Doh set featuring a clay extruder that looks astonishingly like a penis. Hasbro has apologized to consumers offended by the shape of the extruder and has promised a replacement that’s, shall we say, less anatomically correct. Continue reading “The Problem with Phallic Play-Doh”

“It’s Not Mine Anymore…”

Bill Burr: There’s this new level of, like, selfishness when you go to a comedy club, where they’ll watch you for 40 minutes and take everything as a joke, and then all of a sudden you hit a topic that’s sensitive to them and then, all of a sudden, you’re making statements.

Jerry Seinfeld: Right

Bill Burr: I’ve just given into the fact that once I say something now it’s not mine anymore. It literally goes into somebody else’s brain and its cut with their childhood, their experience, whatever happened that day…

Watch the whole episode here.

Setting a Limit

[Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 movie] “Stalker” is a film about a zone, a prohibited space where there are debris, remainders of aliens visiting us. And stalkers are people who specialized in smuggling foreigners who want to visit into this space where you get many magical objects. But the main among them is the room in the middle of this space, where it is claimed your desires will be realized…. [But] there is nothing specific about the zone. It’s purely a place where a certain limit is set. You set a limit, you put a certain zone off-limit, and although things remain exactly the way they were, it’s perceived as another place. Precisely as the place onto which you can project your beliefs, your fears,things from your inner space. In other words, the zone is ultimately the very whiteness of the cinematic screen.

– Slavoj Žižek, “The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema” (2006)

It’s All Ordinary

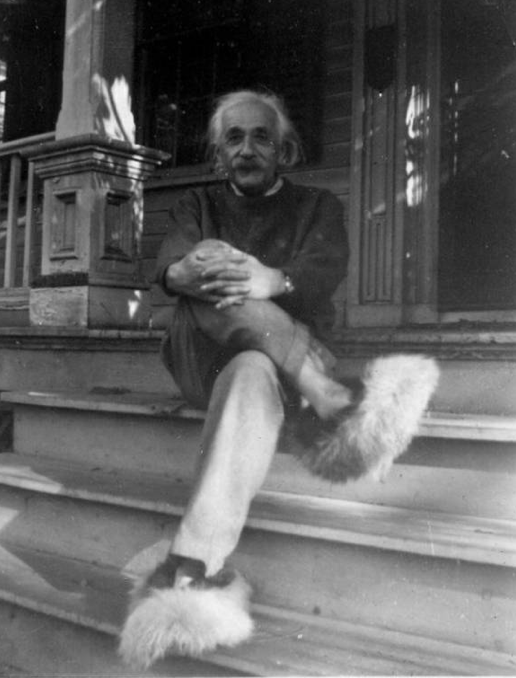

So opens Roland Barthes’ little essay — well known to some, of course — in his collection, Mythologies (read the full essay here). Judging by a recent news story, it turns out that he was right: that the ordinary is continually dressed up as extraordinary and that, at every turn, we make our worlds meaningful by crafting History into Necessity, as he famously phrases it. For the headline of the story, posted here, reads:

So opens Roland Barthes’ little essay — well known to some, of course — in his collection, Mythologies (read the full essay here). Judging by a recent news story, it turns out that he was right: that the ordinary is continually dressed up as extraordinary and that, at every turn, we make our worlds meaningful by crafting History into Necessity, as he famously phrases it. For the headline of the story, posted here, reads:

And voila, Einstein’s brain is, in the Barthean sense, a myth. Continue reading “It’s All Ordinary”

And voila, Einstein’s brain is, in the Barthean sense, a myth. Continue reading “It’s All Ordinary”