My love for the ancient Greek theatre certainly derives from my upbringing and schooling in Thessaloniki, the second largest city in Greece. For many Greeks seeing our ancient literary heritage being performed in outdoor theatres, especially during summer festivals, is certainly seen as being a step closer to our past. Today, the most well-known festival in Greece is the one that takes place every summer (since 1955) in one of our ancient theatres (known also for its great acoustics) the “sacred” (as you will hear it often referenced in Greece) theatre of Epidaurus.

My love for the ancient Greek theatre certainly derives from my upbringing and schooling in Thessaloniki, the second largest city in Greece. For many Greeks seeing our ancient literary heritage being performed in outdoor theatres, especially during summer festivals, is certainly seen as being a step closer to our past. Today, the most well-known festival in Greece is the one that takes place every summer (since 1955) in one of our ancient theatres (known also for its great acoustics) the “sacred” (as you will hear it often referenced in Greece) theatre of Epidaurus.

Every actress/actor in Greece therefore dreams of the day when she/he will be able to perform in Epidaurus. Troupes have to apply to the Festival’s committee, which consists of seven members, and who will decide who will be able to perform each year. In the official site of the Festival where one can find its history, there are references as to how the political situations in Greece since 1955 have affected the criteria and, thus, the selection of the festival’s various performances—often resulting in being more conservative rather than progressive. And this is how the festival, today, describes its purpose:

Every actress/actor in Greece therefore dreams of the day when she/he will be able to perform in Epidaurus. Troupes have to apply to the Festival’s committee, which consists of seven members, and who will decide who will be able to perform each year. In the official site of the Festival where one can find its history, there are references as to how the political situations in Greece since 1955 have affected the criteria and, thus, the selection of the festival’s various performances—often resulting in being more conservative rather than progressive. And this is how the festival, today, describes its purpose:

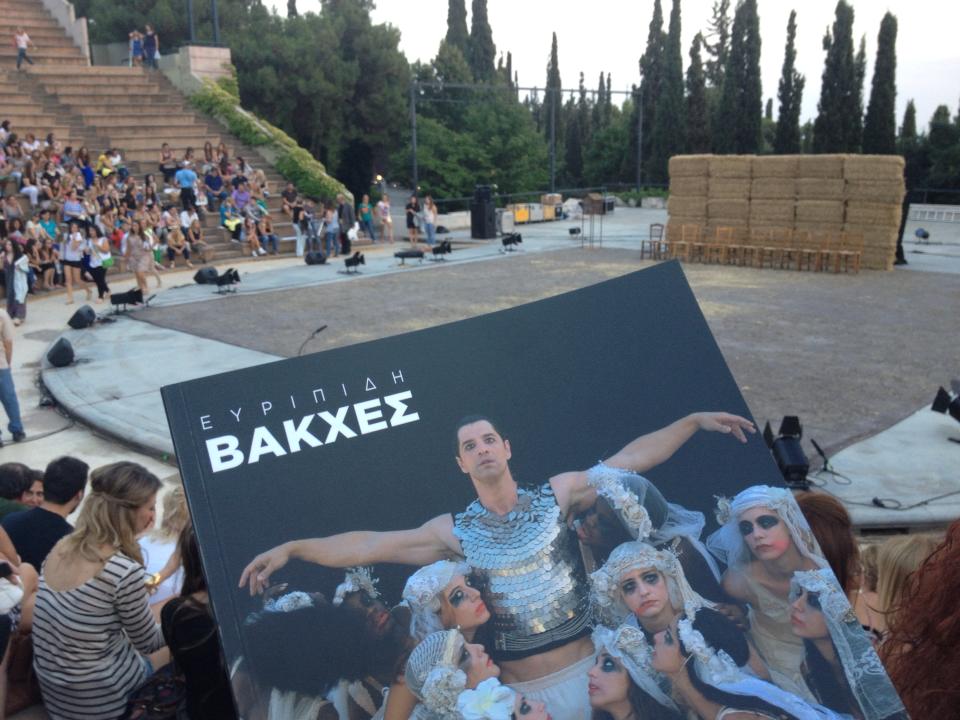

Of course you can’t be inclusive without being exclusive, so some criteria are needed to decide who will annually take part in the festival; there is nothing wrong with that, for not everyone can perform during the festival (which takes place on 8 weekends in July and August) but what attracted my interest this summer—and made me think about the criteria of legitimacy and thus who gets to be authenticated in performing these plays in this specific theatre—was that the application of one troupe in particular was declined. What is special about this troupe, that is performing Euripides’ tragedy “Bacchae,” is that its leading actor is a very popular singer, Sakis Rouvas, who, was sent twice to Eurovision—a very popular song contest in Europe—to represent Greece (a representation based on country-wide voting).

Of course you can’t be inclusive without being exclusive, so some criteria are needed to decide who will annually take part in the festival; there is nothing wrong with that, for not everyone can perform during the festival (which takes place on 8 weekends in July and August) but what attracted my interest this summer—and made me think about the criteria of legitimacy and thus who gets to be authenticated in performing these plays in this specific theatre—was that the application of one troupe in particular was declined. What is special about this troupe, that is performing Euripides’ tragedy “Bacchae,” is that its leading actor is a very popular singer, Sakis Rouvas, who, was sent twice to Eurovision—a very popular song contest in Europe—to represent Greece (a representation based on country-wide voting).

It’s of interest to know that the Eurovision song contest is a specifically popular (as in “pop”) song contest open to any European singer/group who wishes to participate, and which takes place every May in the European country (since 1956) that won the previous year’s contest. Every country has individual competitions of its own prior to that, and committees, or the public or both vote on which participant will represent their country each year. Same in Greece: singers and groups apply to the public television broadcaster (ERT), which is responsible for the contest in Greece. The interesting thing is that since 1974 (when Greece joined the Eurovision contest) Rouvas is the only singer to represent Greece twice in the contest (in 2004 and 2009) by direct appointment from the public television company (ERT), i.e., without competing against any other singers.

And although his participation in the Eurovision contest was highly acceptable to the Greek public, as noted above, it was not the case when he decided to perform in an ancient tragedy (which I saw in Thessaloniki and this is where the first picture above is from). There have been various comments in the media—mostly critical—regarding a pop singer’s participation in an ancient tragedy, concluding that it is unacceptable to perform in Epidaurus despite him being a young and widely popular artist and, more importantly perhaps, despite the need of the festival (as described on its site) to “seek out new and different audience.” According to one journalist the festival declined the application of the troupe exactly because Rouvas was a performer: “The people of the Greek Festival was hesitant and feared that the presence of a pop star will ‘irritate’ the most conservative of both artists and viewers and so backed away.”

Why I find this whole episode interesting, though, is not so much as to whether the committee decided against Rouvas participation in the Epidaurous festival, rightly or not, but, rather, the way criteria of legitimation (criteria that are themselves historical products, and thus constantly changing) work. For I assume that there is in most Greeks a very clear idea/image of who should perform in that theatre. Of course it needs further investigation but my hunch is (well it’s more than a hunch) that a certain ideology is being translated in criteria of legitimation to create a certain identity, both of the festival but also of how “our” past should be portrayed and thus by whom—thereby making “us” today into a certain sort of Greece. In other words, there is nothing self-evidently natural about who ought to be able to represent the so-called classics; on the contrary, unnoticed criteria are always in operation and they create, promote and authenticate both the actor and the group judging him.