The first time I came to Edmonton, Canada, was in March of 2010, in order to give a paper at a conference, and, since I had applied for a Ph.D. there, to also see the city—not knowing though whether I was yet accepted at the program or not. That was the first time I had been so far north and the only thing I knew for sure was that Canada is cold (that the temperature could get as low as -30C (-22F) was beyond what my imagination could grasp). As I said, it was mid-March when I arrived and to my surprise what I saw—as we were descending into the International Airport in Edmonton—didn’t look like Spring to me at all (The Edge’s Monical Miller knows what I’m talking about, given that she visited me last March!); everything was covered in a thick white blanket, so much snow I’ve never seen in my life. At the airport Willi Braun, my supervisor now, came to pick me up and as we got out of the airport I remember saying something about how cold it was (I can’t recall now what the temperature was, of course—but for those who are not from Canada, or some place north, when I say everything was covered with snow, well it’s not that difficult for you to imagine that it was cold), at which point Willi corrected me, saying that it was not cold but just chilly. I wasn’t really sure what to make of his correction at the time, and this subtle distinction, because to me chilly still felt cold and that was my first encounter with Edmonton’s weather.

The first time I came to Edmonton, Canada, was in March of 2010, in order to give a paper at a conference, and, since I had applied for a Ph.D. there, to also see the city—not knowing though whether I was yet accepted at the program or not. That was the first time I had been so far north and the only thing I knew for sure was that Canada is cold (that the temperature could get as low as -30C (-22F) was beyond what my imagination could grasp). As I said, it was mid-March when I arrived and to my surprise what I saw—as we were descending into the International Airport in Edmonton—didn’t look like Spring to me at all (The Edge’s Monical Miller knows what I’m talking about, given that she visited me last March!); everything was covered in a thick white blanket, so much snow I’ve never seen in my life. At the airport Willi Braun, my supervisor now, came to pick me up and as we got out of the airport I remember saying something about how cold it was (I can’t recall now what the temperature was, of course—but for those who are not from Canada, or some place north, when I say everything was covered with snow, well it’s not that difficult for you to imagine that it was cold), at which point Willi corrected me, saying that it was not cold but just chilly. I wasn’t really sure what to make of his correction at the time, and this subtle distinction, because to me chilly still felt cold and that was my first encounter with Edmonton’s weather.

Oh, during my stay, they were also saying something about the “windshield,” too, but I couldn’t figure that one out; maybe you needed a shield to protect you from that wind!

A few months later I would return as a Ph.D. candidate, and around October—although they called it Autumn it did feel like Winter to me (though it is of no surprise that our “Winter Semester” is from January to April)—I would occasionally ask Willi if it was yet legitimate for me to say “it’s cold,” and with his refusal I was offered yet more adjectives. One time I emailed him:

Me: Well is it cold yet?

Willi: You will have to wait a bit longer, my dear. I would call this biting or sharp. Both words imply pain. But when it is cold the pain is gone.

Me: But if the pain is gone…oh no!

Willi: Yes, one could speak more positively. You might revive the old dog metaphor for measuring temperature on the minus end of the thermometer. In the olden days up here in the northern lands, cowboys, ranchers and hunters would have to sleep with their dogs to keep warm. To this day you might hear people around here speak of a “one-dog night” (you need to sleep with one dog to keep warm) or a two-dog night, and so on. I would say we are in the one-dog night range. Definitely not in the hot dog range. That would be Alabama.

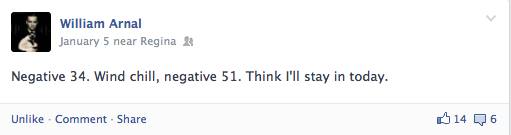

Over the years I’ve learned that the weather can change from “cool,” to “crisp,” “brisk,” “nippy,” to “biting” and “sharp” (as my Professor described it), then to “cold,” “frigid,” and “freezing cold” or even counting the cold with dogs! Not to mention that it doesn’t just snow, there are “scattered flurries,” “flurries,” “freezing rain,” “wet snow” and who knows what else. And I also learned that it’s not enough to know that it’s -16C (3.2F) because, depending on the “wind chill” (and not the windshield as I initially thought) it could easily feel like -26C (-14.8F) and that’s “cold,” not “frigid” or “freezing cold,” though, as is more usually the case in the prairies of Saskatchewan, at least according to the regular FB updates I see on William Arnal’s wall.

As you might understand, describing “cold” is a complex and certainly a necessary taxonomy in my neck of the woods, because without such distinctions the weather here would simply be cold 8 months of the year, and believe me that’s not good.

What this story of distinction may tell you is that insiders have the luxury of nuance, a process that marks their place. It enables a narrative—moving from nippy to freezing—that helps, in some ways, people here to cope with the long lasting winters. It is hopeful to say “it’s a chilly day” and not “it’s a cold day” and it’s dreary to think that the worse is yet to come. But I suppose there is something to be gained by this movement from cool to freezing, because, as you know, it can always get worse: “freezing cold” for a day or two (or even a bit longer) is not that bad, as you also know that it will be “balmy” (as Marcia Hay-McCutcheon, a good friend in Alabama, once described it for me) when it goes back to -5C (23F), and that’s a hopeful thought. Our narratives, our classifications, our distinctions, if you will, therefore don’t necessarily describe some natural reality out there, instead, they allow us to cope with the everyday, to make sense of it and live in it. That’s why I guess when I say to my friends in Greece that minus 15C (5F) is actually nice—“it’s a different cold”—they look at me with distrust, because for them it’s just “cold”; but we don’t have the same things at stake, do we? I mean, they don’t have to live where I live so the nuances of “cold” are of no relevance to them.

After four winters in Edmonton I not only have all this vocabulary in mind to cope with the winter wonderland, but I also feel more of an insider, that is being able to distinguish between these subtle gradations of coolness. So when it is only starting to get a bit chilly in early October and I hear newcomer students (often from warmer climates like myself)—in the University’s residence where I live—complaining about how cold it is, I immediately tell them that they should do well by reserving that word for January and February or even March, and that they shouldn’t forget the wind chill.