It occurred to me sometime ago that when we pour something we’re not actually pouring anything. Continue reading “Misattributions”

A Peer Reviewed Blog

It occurred to me sometime ago that when we pour something we’re not actually pouring anything. Continue reading “Misattributions”

In a recent interview, the creator and primary writer of the British anthology series, Black Mirror, Charlie Brooker, offered the following commentary on selves and social media.

Social media has made it…, and the internet and technology in general, has sharpened all of those things — I guess they’ve always been there, that performative nature of life, has always been there, that you sort of perform your personality, I guess, to everyone, on some level. I remember…, my theory is that we’ve got…, that we used to have several personalities and now we’re encouraged to have one, online. By which I mean…, I remember once having a birthday party and people from different aspects of my life showed up…, and I behaved differently with all of these people, in the real world, but once they were all together in one space, and they were all mingled in, in one group, if I walked over to them I suddenly didn’t know how to speak. Do you know what I mean? Because like, with some of them I’d try to be all intellectual and erudite and with others I’d just swear and curse and be an idiot. And suddenly when they’re all in one space I don’t know who I am. And I kind’a feel like one sort of thing is that online you’re encouraged to perform one personality for everyone. And I wonder if that’s one of the things that’s feeding into the kind of polarization that seems to be going on…. I think that lends itself to group-think, in some way… I wonder if we’re better equipped to deal with having slightly different personas…, that come out when you interact with different types of people.

For the full interview, see 28:46 onward from this episode of Fresh Air.

Watch the trailer for the newly released third season:

A New Jersey fundraiser last weekend titled “Humanity United Against Terror” provides an excellent example of one of the tricks of building cooperation. The Republican Hindu Coalition organized the event that featured Bollywood stars and an address by Donald Trump. The event had a range of interesting incongruities, including signs suggesting that Trump would ease speed up immigration and images depicting Hillary Clinton and Sonia Gandhi (leader of the Congress Party in India) as demonic. My focus, however, is the framing of the event, contrasting the title and general purpose to its content, which in large part served as a political rally for Trump’s campaign. Continue reading “Building Broad Support (or the Appearance of it)”

A New Jersey fundraiser last weekend titled “Humanity United Against Terror” provides an excellent example of one of the tricks of building cooperation. The Republican Hindu Coalition organized the event that featured Bollywood stars and an address by Donald Trump. The event had a range of interesting incongruities, including signs suggesting that Trump would ease speed up immigration and images depicting Hillary Clinton and Sonia Gandhi (leader of the Congress Party in India) as demonic. My focus, however, is the framing of the event, contrasting the title and general purpose to its content, which in large part served as a political rally for Trump’s campaign. Continue reading “Building Broad Support (or the Appearance of it)”

There has lately been a flurry of talk at my house about picture-taking. First, there were the beginning of school pictures for the yearbook. Next, there were the soccer pictures to accompany the end of the season (which is just now occurring). Finally, one of my kids had a special school project that involved taking pictures of him in various stages of engagement with a special stuffed animal; this animal was our houseguest this weekend in honor of my son’s turn as “Student of the Week” in his class.

What struck me about all of these picture was not just the flurry of activity that we devoted to their creation, but my response to the picture-taking process (and, ultimately, the pictures themselves). For my almost-teenage daughter, school pictures are essentially a litmus test of her self worth, and thus she spent considerable time planning hairstyles, clothes, and different sorts of smiles to pull off the look she wanted. When she got her pictures home a few weeks ago, they were just as she had practiced. Everyone was pleased. Continue reading “Picture Day”

Eventually, peace was going to be built on the distinction between public and private affairs. Conscience had fought with pope and emperor for control of the world. Both had claimed universal rights. When both realized that victory was out of reach, they agreed to divide the spoils. And in so doing they transformed themselves into the shape in which we have known them ever since: a conscience that makes no claims on politics and a politics that makes no claims on conscience. Conscience was recognized, but only as a private voice that had no right to public force, except indirectly, through peaceful debate. Augsburg‘s abstention [in 1555] from settling questions of religion by force was thus kept intact. But it was also made legitimate by a new distinction between politics and religion that had lain beyond the imagination of the sixteenth century. Sovereigns reciprocated by surrendering the rights claimed by their universal predecessors to govern the consciences of their subjects. Religious faith was abandoned as a foundation of the commonwealth. Its place was taken by a faith in the distinction between public and private matters that helped to restore obedience to law…. By means of the distinction between private and public affairs, church and state, morality and positive law, Europe thus managed to build the institutions that brought back peace and then enabled it to extend its reach across the globe — much as by means of the distinction between spiritual office and temporal fief, pope and emperor had managed at an earlier time in European history to divide the world between themselves and put an end to the Investiture Controversy, that high medieval analog to the early modern wars of religion.

– Constantin Fasolt, The Limits of History (2004: 137-8).

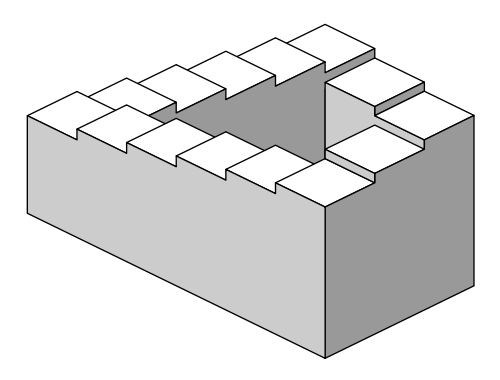

Why do we see this image of the Penrose Stairs as being impossible? Optical illusions, such as this one, and magic tricks function because of at least two structures, perhaps we should call them limitations, related to our perception of reality, namely bodily structures (our sensory system) and conceptual structures )the frameworks around which we organize those perceptions). Considering these limitations becomes important not only for our perception of illusions but also for the work of observation and description that informs much scholarship and public discourse.

These reflections came out of watching David Blaine perform his ice pick trick in a conversation with Neil DeGrasse Tyson with Pharrell Williams and Scott Vener in their OtherTone Studio. Continue reading “Illusions, Magic, and the Perception of Reality”