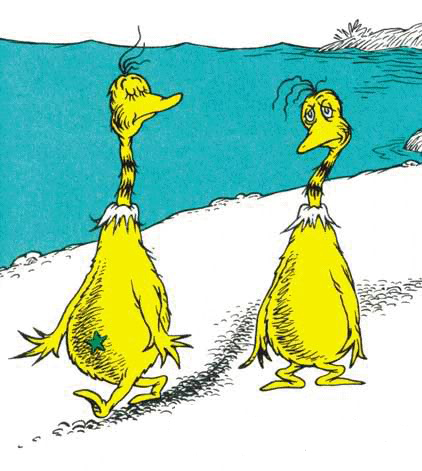

Do you know the tale of the Sneetches? It’s a Dr. Seuss story, published in 1961, about the inhabitants of a beach who are exactly the same apart from some having stars on their bellies. It’s a difference with no necessary significance, but it soon takes on consequence, of course.

Do you know the tale of the Sneetches? It’s a Dr. Seuss story, published in 1961, about the inhabitants of a beach who are exactly the same apart from some having stars on their bellies. It’s a difference with no necessary significance, but it soon takes on consequence, of course.

Now, the Star-Bell Sneetches had bellies with stars.

The Plain-Belly Sneetches had none upon thars.

Those stars weren’t so big. They were really so small.

You might think such a thing wouldn’t matter at all.But, because they had stars, all the Star-Belly Sneetches

Would brag, “We’re the best kind of Sneetch on the beaches.”

With their snoots in the air, they would sniff and they’d snort

“We’ll have nothing to do with the Plain-Belly sort!”

And, whenever they met some, when they were out walking,

They’d hike right on past them without even talking…

If you don’t know the story, then I won’t spoil it (too much); suffice it to say that a quaint lesson in tolerance is learned by everyone after Sylvester McMonkey McBean comes to town and swindles them all with his matching (and costly) Star-On and Star-Off machines — creating a perfectly capitalist economy of figure-eight paying customers, in which our only goal is not to be whatever they happen to be.

Apart from the happy ending, it’s a great story that’s pretty sophisticated, for it not only demonstrates nicely that difference has no substance and that value and identity are situationally concocted and thus relative, but also that mere distinction inevitably gets arranged hierarchically. That is to say, while distinction and hierarchy may be separable analytically, in practice it’s pretty tough to find one without the other. Star or no star? Well, then stars are better to have (or not). Boys or girls? Well, girls are more sensitive or, instead, boys are more confident. Old or young? Well, seasoned veterans are more experienced, or, instead, newcomers are more adventurous.

Apart from the happy ending, it’s a great story that’s pretty sophisticated, for it not only demonstrates nicely that difference has no substance and that value and identity are situationally concocted and thus relative, but also that mere distinction inevitably gets arranged hierarchically. That is to say, while distinction and hierarchy may be separable analytically, in practice it’s pretty tough to find one without the other. Star or no star? Well, then stars are better to have (or not). Boys or girls? Well, girls are more sensitive or, instead, boys are more confident. Old or young? Well, seasoned veterans are more experienced, or, instead, newcomers are more adventurous.

Show me a generic difference and I’ll show you a normative system of value and identification riding along closely behind it.

But why?

It seems to me that the world is filled with differences — just look around; everything is different from everything else in innumerable ways. There’s too many to even pay attention to. The question, then, is which sets of differences are worth talking about? So it appears that only those distinctions that prove useful to us attract our attention, and those that are useful are the ones that enable us to distinguish us from them, normal from abnormal, accepted from unaccepted, here from there, then from now, legal from illegal, wanted from unwanted, etc. That is, the observation of mere difference really isn’t all that handy — “Oh, look, you have four buttons on your shirt and I have five” — while differences that can be overlaid with interests, difference than come to have consequence, are endlessly useful — for now it’s: “Oh, you’re missing a button? Then you’re disheveled, you don’t take pride in your appearance, and you can’t take care of yourself.”

The moral of the tale? Where you find a discourse on difference — any type of difference, any taxonomy, any system of classification — you’ll probably also find a normative discourse on value, development, and identity, all of which ensures that some arbitrary distinction becomes the basis for managing people and things.

Seuss seems to go out of his way to clarify that it’s a single, minor, eradicable cosmetic difference, which has no bearing on function.

How then the moral, All differences are meaningless and lead to similar kinds of oppression?