There’s been lots of buzz, over the past decade or so, about material religion or embodied religion, as if this apparent emphasis on the empirical, the contingent, the historical, somehow gets us out of what many now see as the old rut of studying disembodied beliefs alone.

There’s been lots of buzz, over the past decade or so, about material religion or embodied religion, as if this apparent emphasis on the empirical, the contingent, the historical, somehow gets us out of what many now see as the old rut of studying disembodied beliefs alone.

For instance, take the following quote (from the opening to their first newsletter) from the late 1990s/early 2000s Material History of American Religion Project centered at the Divinity School of Vanderbilt University, funded (like much scholarship on religion in America) by the Lilly Endowment, and involving several key figures in the early years of this movement:

[T]he scholars associated with this project have set out to pay attention to a neglected dimension of the history of religion in America. Too often the story of religion has been told as though it were a matter of thoughts and ideals alone. Material history is embodied history and recognizes that religious people have enacted their spiritual beliefs and religious ideals in a very material world. We are looking at the material evidence, getting into the material, and finding out a great deal in the first year of this project.

Dare we ask: Material evidence of what…? Well, apparently of the beliefs, faiths, experiences, etc. — i.e., “enacted their spiritual lives and religious ideals” — that are somehow assumed to motivate people to do this or that with their bodies.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose, non?

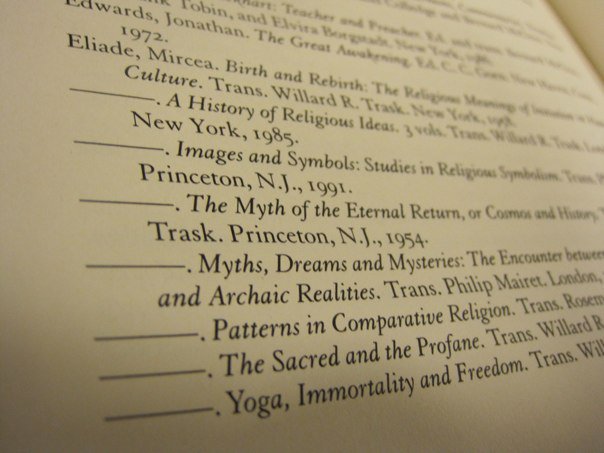

My point? I am at a loss to explain how — apart from, say, changing the old word “manifestation” to the sexy new “embodiment” — this new approach is any different from the old approach that once dominated our field, represented so nicely by the work of Mircea Eliade and those others who drew on hermeneutics and phenomenology to come up with a method to somehow “get at” what they considered to be the essential and historically universal sine qua non of religion. For in both cases, “that which presents itself to our senses” (as they used to say, as if the world marched toward us of its own accord) is assumed to be evidence of a something else — and that something else is asserted to be non-empirical and can only be inferred from our so-called historical, descriptive, and comparative studies. Call it faith, call it belief, call it spirit, or call it soul, I’m not sure what difference it makes, for what these two approaches share is a presumption that history is merely an arbitrary stage on which ahistorical themes and dispositions of universal scope are played out.

But given that Lilly supported the above quoted project, maybe none of this should come as a surprise. After all, as the Foundation phrases its mission:

The ultimate aim of Lilly Endowment’s religion grantmaking is to deepen and enrich the religious lives of American Christians, primarily by helping to strengthen their congregations. To that end, our religion grantmaking in recent years has consisted largely of a series of major, interlocking initiatives aimed at enhancing and sustaining the quality of ministry in American congregations and parishes.

It seems to me that a scholarly approach that heralds the empirical, but which is in the service of conserving the common assumption concerning the primacy of a non-empirical spirituality and inspiration, quite nicely enhances and sustains the participant’s viewpoint. No wonder that such work earns grants.

The question is, though, whether a mere paraphrase of what people are already saying about themselves and their lives constitutes scholarship.

Query: How would Women’s Studies fit with regard to this criticism? A fair bit of early work in the field was devoted to “hearing women’s voices.”

Aside: lest I be accused of creating a strawman (or lady) by quoting an older initiative (by some of the founders of this entire subfield, by the way), then give this a listen and tell me how it differs from phenomenology:

http://www.religiousstudiesproject.com/podcast/podcast-david-morgan-on-material-religion/

My hope is that it was not aimed at deepening and enriching women’s lives (that’s what I thought the feminist movement as a whole might have been about) but, instead, theorizing the power differentials, theorizing gender categorization, etc., and thereby understanding these things as historical practices that leave traces and could therefore be otherwise–who knows what other way, but otherwise (seeing them as contingent and not natural or necessary). If “hearing women’s voices” was all about enriching their lives (and who counted as “women”? as the old debate then raged) then I’m not sure how it constitutes scholarship.

RE: WS/feminist scholarship – there is an awful lot in the earlier writing about even being able to name that there was a problem. Being able to speak is a privilege granted by others. Self-censoring and self-blaming strangles the voice. Speaking out – without fear (or terror – reprisal for women speaking is still pretty grim) – is extremely difficult for those who have been systemically silenced. So I guess I have two points to make: ) speaking and being heard are necessary precursers to systemic analysis for those who have been silenced and 2) a depersonalized stance as a marker of clear, appropriate study (scholarship? Knowledge-making?) has been one of the most effective tools for subordinating the non-dominant. (I think I talked a bit about this in Making the Gender-Critical Turn).

I was ready to get defensive because in general I’m a big fan of Morgan’s work, but you’re right, part of this interview is a mess.

Q: “What is material religion?”

A: “It’s the shift to looking at how religious material culture constructs the worlds of belief.”

I think part of it is a sloppiness with the language: Remove the qualifier “religious” from “material culture,” and substitute “rhetoric of belief” or “conceptual boundaries” for “worlds of belief” and you’ve got a stronger response.

I can’t hop on the one-way train that goes all the way to Rhetoric-Only Town because I still think epistemological variance is an aspect of human life that needs to be considered, especially on a cultural level. But by accepting that, I’ve accepted the scholarly slippage into essence-speak

Interesting… It is an essentially slippery slope, isn’t it…? Such researchers do not strike me as interested in, say, the category religion as some of us are but, instead, how religion or faith or spirituality, whatever they opt to call this it (that they already know to exist prior to categorization) gets managed by improper categorization–if you read/listen to them carefully it becomes apparent that the old essence/manifestation distinction informs their work–they are not trying to theorize individualism but, instead, trying to figure out a way for what they somehow know to be the authentic individual to be expressed properly for social effects they value. Ritual, institution, language, etc., for them, are derivative realms of mere expression–nothing has really changed but they’ve done a masterful job to make what they do sound new and improved. A marketing class in a business school ought to study them since they sold old Coke incredibly well.

I don’t disagree, but my hunch is that there’s all kinds of voices on what women ought or ought not to do (like those voices silencing women, or certain groups of women…) that you wish to silence or see as illegitimate scholarship–no? So if its hardly a come-one-come-all, happy pluralistic big tent then then we’re stuck with the situation of making calls on allows/not allowed, right? Calls that shape the social world in ways we find conducive to sets of interests we hold…