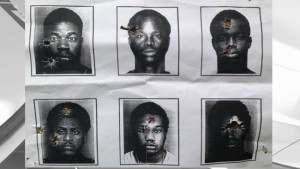

As Americans today celebrate Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, many of us continue to grapple with how to contextualize and understand the recent deaths of several young black American men at the hands of the police. This need to explain is thrown into even starker relief with the very recent story that black men’s photos are being used for target practice by the North Miami Beach police department. The chief of police insists that this is a case of “poor judgment,” not racism, because those officers taking aim at the targets are themselves multi-racial, and because other races are portrayed in other targets. As one might expect, however, at least one of the black men whose face became a target is not personally reassured, saying, “Now I’m being used as a target? … I’m a father. I’m a husband. I’m a career man. I work 9-to-5.”

It may seem quite paradoxical to discuss a “well-intentioned racist,” but arguably, there is usually no other kind. I am often amazed by how we expect that racism (or discrimination, more generally) is something committed by self-described bigots. Like many others who study and teach about social dynamics, I frequently tell my students that prejudicial behaviors and attitudes are not only ubiquitous, but also quite mundane — they are simply the old recipe of one part distinction and another part essentialization — and they are used to stir the stew of social power. Continue reading “The Well-Intentioned Racist”

I always breathe a sigh of relief when Christmas is over. Don’t get me wrong – I like Christmas carols, watching my kids open gifts, and the smell of Christmas trees, so I’m not a total Scrooge about the affair. But the logistics of travel, the cost of those gifts, the “We put up the decorations; We take down the decorations!” cycle is enough to leave me eager for January.

I always breathe a sigh of relief when Christmas is over. Don’t get me wrong – I like Christmas carols, watching my kids open gifts, and the smell of Christmas trees, so I’m not a total Scrooge about the affair. But the logistics of travel, the cost of those gifts, the “We put up the decorations; We take down the decorations!” cycle is enough to leave me eager for January.

Asking about my favorite non-theory book is kind of like asking about my favorite child. As such, I’ll dodge that question and say that it’s a tie between all of the Harry Potter books and all of the Daniel Woodrell books. The first Woodrell book I read was Tomato Red. Next was The Death of Sweet Mister, followed by Winter’s Bone (remember that Jennifer Lawrence movie? Woodrell wrote the book), and all of the others shortly followed (most recently for me, The Maid’s Version). The Harry Potter books don’t need any sort of explanation, I suspect. But Daniel Woodrell might, and he’s well worth the introduction.

Asking about my favorite non-theory book is kind of like asking about my favorite child. As such, I’ll dodge that question and say that it’s a tie between all of the Harry Potter books and all of the Daniel Woodrell books. The first Woodrell book I read was Tomato Red. Next was The Death of Sweet Mister, followed by Winter’s Bone (remember that Jennifer Lawrence movie? Woodrell wrote the book), and all of the others shortly followed (most recently for me, The Maid’s Version). The Harry Potter books don’t need any sort of explanation, I suspect. But Daniel Woodrell might, and he’s well worth the introduction. Bruce Lincoln, Holy Terrors: Thinking About Religion After 9/11 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003)

Bruce Lincoln, Holy Terrors: Thinking About Religion After 9/11 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003)

I remember standing in the checkout line at the campus bookstore with my copy of Roland Barthes Mythologies. I admit that I was suspicious of any book supposedly so profound that was also so small. Its size is deceiving just as much as its structure is unique: the first part of Mythologies is comprised of a series of short essays that provide the pop-culture exemplars of Barthes’ theory on how mythmaking operates (covering everything from food to clothing to politics), while the latter half is comprised of a theoretical essay – entitled simply “Myth Today” – that more overtly addresses the workings of this type of semiotic turn. Barthes rejected common definitions of myth that equate it with “falsehood” or “the stories that dead people believed.” Rather, Barthes understood myth as an absolutely ubiquitous process that involves the transformation of “history into nature,” or, put differently, the manner in which otherwise constructed things are made to appear natural or inevitable.

I remember standing in the checkout line at the campus bookstore with my copy of Roland Barthes Mythologies. I admit that I was suspicious of any book supposedly so profound that was also so small. Its size is deceiving just as much as its structure is unique: the first part of Mythologies is comprised of a series of short essays that provide the pop-culture exemplars of Barthes’ theory on how mythmaking operates (covering everything from food to clothing to politics), while the latter half is comprised of a theoretical essay – entitled simply “Myth Today” – that more overtly addresses the workings of this type of semiotic turn. Barthes rejected common definitions of myth that equate it with “falsehood” or “the stories that dead people believed.” Rather, Barthes understood myth as an absolutely ubiquitous process that involves the transformation of “history into nature,” or, put differently, the manner in which otherwise constructed things are made to appear natural or inevitable.