After one of my kids was diagnosed with a health condition last year, our doctor recommended that our whole family radically change what (we believed) was our otherwise healthy diet and embrace a way of eating that has popularly become known as the Paleo diet. “Paleo” is a term used to reference what many say were the eating habits of Paleolithic-era humans (more on that in a moment). This approach to food emphasizes the consumption of lean meats, veggies, fruits, and nuts (all things that one would hunt and/or gather, so the story goes) at the same time that it eschews grains, dairy, legumes, and all refined, processed, or artificial foods.

A little internet reading could easily convince the novitiate that there is a Paleo god looking to strike dead those who stray from its parameters, for there are a myriad of Paleo folks out there who argue vehemently about what constitutes the “truest” Paleo lifestyle. Despite their differences, the philosophical tie that unites most Paleo adherents is the sense that “eating like a caveman” is the most “natural” and “authentic” approach to food possible, one closest to how our bodies are “designed” to be fed. Good health is often promised as the result of firm adherence to the philosophy, and this is the rationale Paleophiles have long provided for why so many people experience a multitude of positive health benefits when they follow it.

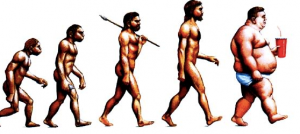

Yet those of us interested in the social dynamics of a good origin story know that one of the most magical things about it is not only that it’s almost always unproveable, but that such stories barter in that ever-persuasive language of authenticity and naturalness. Put simply, the assumption is in place that anything and everything that Paleo humans did was so natural that if we can just figure out their habits, then the key to health lies closely by. If you read certain Paleo websites, you will receive a full-on history on the stellar health of humans prior to the birth of agriculture (a point in time marked by the production of the grains upon which modern processed diets so frequently depend). After this point, the story continues, that crazy homo-sapien clan started to roll down the slippery slope towards “all-McDonalds, all the time” eating, reaping disease along the way.

Yet when researchers recently announced that they had found the skeletons of Paleolithic humans with advanced tooth-decay caused by the ingestion of an ongoing diet of sugary acorns, many in the Paleo world were quick to pronounce this a dietary aberration; tooth decay is one of the things on a long list of ailments that hard-core Paleo folks argue didn’t happen until human grain consumption increased. So how do people handle evidence that contradicts the original story? Rather than being a scientific issue, I prefer to approach this as a social one, for this blip in the Paleo narrative gives those of us interested in identity the opportunity to expose how it works.

While some ignored the historical narrative altogether and instead focused on the fossil as an emblem of the damage that carbs wreak on the body, the way that most in the Paleo community dealt with this new information was to find a hypothesis that would change the origin narrative to accommodate the data (“Was there a famine or other disruption in their food supply and only acorns remained?,” for instance). Changing the story is effective because it leaves intact the basic practices of the group: eat protein and produce, avoid carbs and grains. But even a detour in the narrative doesn’t necessarily resolve much, for it leaves us an only slightly altered – and still ultimately unproveable – story that continues to hinge on a highly politicized construction of “health” and “nature.”

So while juggling around an origin story is certainly a way to negotiate identities when they are challenged, what strikes me as an even more interesting (and fundamental) rhetorical move is the manner in which the term “natural” is construed in the first place. Across the Paleo movement, “natural” almost always means “healthy,” and yet here we have a caveman with a sweet tooth whose holey jawbone wrests those two symbols apart. This begs the question of why certain human acts are called “natural” and what we mean by the term.

For instance, by most modern dietary standards today, a food is called “natural” when it contains ingredients that can be found in their present form in nature. This is why something like hydrogenation (a process that makes many oils shelf-stable – think Crisco) is considered “unnatural” even though it involves the manipulation of otherwise natural products (hydrogen and various natural oils).

By this measure, though, very little that we eat is truly “natural,” for we do not “naturally” find chickens lying, fully cooked, in the fields where they were previously pecking, nor do we find bottles of olive oil just hanging from trees. In short, if what we call “natural foods” have to be subjected to humans, their tools, and their processes in order to fit the dietary parameters by which we operate today, then why is the process of pushing natural hydrogen through natural oils “unnatural,” but pressing the oil out of natural olives somehow “natural”?

For Paleo adherents who are looking for philosophical consistency, the answer can’t be measured in terms of health, for we have already seen where that got the “natural” cavemen who hoarded “natural” acorns. Instead, I want to suggest that this conversation is about recognizing that what counts as “natural” isn’t a fixed standard as much as it is a barometer of social sentiment with some science thrown in. Large parts of the idyllic past on which the Paleo narrative depends may never have existed, or at the very least are hopelessly unproveable. Yet because they cannot be neither proven nor disproven, such pasts are a convenient and efficient rhetorical canvas on which to paint any number of convincing narratives.

So rather than couch the term “natural” as a descriptor of an essential human state long lost to the past, I see the term’s use in Paleo communities as little more than an authoritative code word for a providential-type speech that relies heavily on notions of destiny in design — one of the most popular stories ever. This makes the Paleo narrative an excellent marketing tool much more than it is an historical, or even scientific, explanation. For me, I’m sold on this way of eating, and have no plans to stop. But even though I like how it makes me feel, that doesn’t make its origins stories any less political.

Photo credit: under20workout.com

I love how you sum it up right here about natural and unnatural foods: “By this measure, though, very little that we eat is truly “natural,” for we do not “naturally” find chickens lying, fully cooked, in the fields where they were previously pecking, nor do we find bottles of olive oil just hanging from trees. In short, if what we call “natural foods” have to be subjected to humans, their tools, and their processes in order to fit the dietary parameters by which we operate today, then why is the process of pushing natural hydrogen through natural oils “unnatural,” but pressing the oil out of natural olives somehow “natural”?”

This is a great explanation of how things over time have changed in dietary intake. The world is different than when paleo was the way people normally ate. Doesn’t mean it’s wrong, but I believe what it comes down to is what is good for the body overall. What should we introduce into the body that is “good” for it, on the most and to the highest levels. That will promote health for the entire body?