Recently on Twitter, I was reflecting about the everyday encounters where the study of religion (and really “religion” as identity formation) becomes a topic of conversation.

In case it’s TL;DR, the long and short is that I’m convinced that there’s plenty of opportunity for scholars to contribute to public discourse if we hold vigilant in our commitment to observation and intelligibility. To me, the minute that we insist upon our expertise at the expense of our willingness to explain our point is when we’ve shifted a potential exchange with someone into an effort to change the other.

And while I prefer to see change as a social fact rather than an intrinsically bad thing, there is something disturbing about clearly veiled efforts at affecting change. They are all well and good when they go unnoticed, like the way I hand my kids a sealed salt shaker when they want to add more seasoning to their food. But when we know how this works, we label these acts differently–manipulation, lying, bait-and-switch, etc.

It’s the trick-or-treat conundrum.

A line in a recent article by Sierra Lawson & Steven Ramey got me thinking about how this works in the medical field. They looked specifically at how a 2015 nursing textbook drew upon questionable racial, ethnic, and religious characterizations in an effort to equip students for “Transcultural Nursing,” a framework for providing culturally relevant aid in cosmopolitan spaces. But as Lawson & Ramey investigated the characterizations and sources, they saw how our treatments of diversity can quickly become too “generalized” at best, or “prejudicial,” at worst. The authors go on to draw parallels to the way many departments of Religious Studies use the “World Religions paradigm” in introductory survey classes, but I saw another parallel in the medical profession: vaccinations.

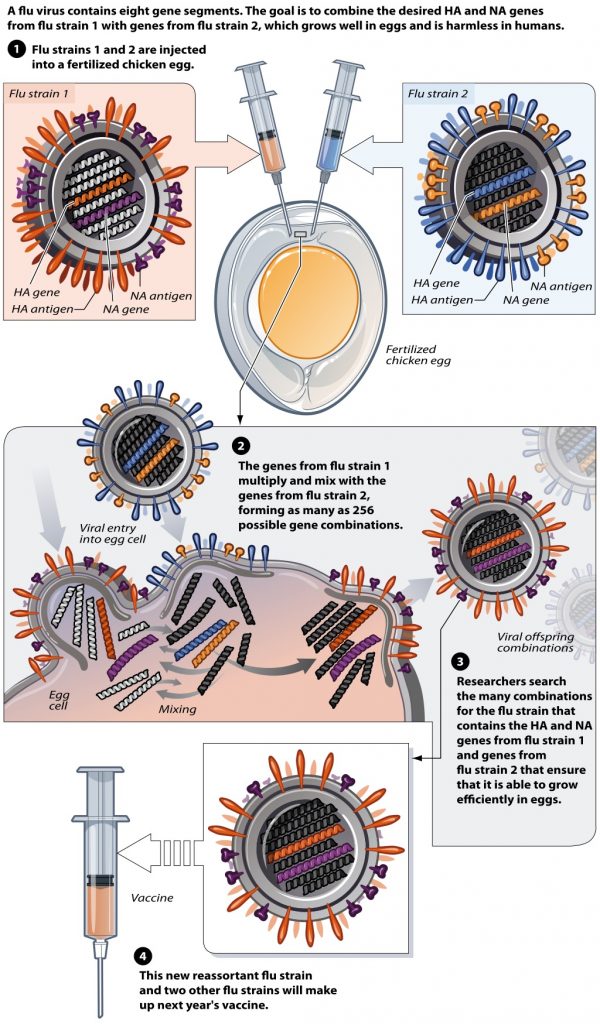

In the US, flu vaccinations are a public health bonanza. Schools, business, and community centers have partnered with agencies to offer low-to-no cost shots to stave off an epidemic. Additionally, public schools can require certain students to follow certain immunization schedules. But as a doctor recently lamented to me, some families can forgo these through “religious exemptions.”

Having some idea what I do for a living, the doctor asked if there is anything medical practitioners can cite in order to encourage the abstinent to have a change of heart.

It was gut-check time, or as Lawson & Ramey put it:

Whatever presumably good intentions the scholars have, the negative implications of such processes that authorize particular social hierarchies require scholars to reconsider the choices that we make in constructing and presenting simplified knowledge.

Sure, I could come up with a list of a few hermeneutical loopholes to assist the doctor, but that sounds ethically tricky to me. And serving as the doctor’s trump card doesn’t sound like good bedside manner, even though under different conditions we could describe our collaboration as proof of the humanities’ relevance or interdisciplinary or public scholarship.

But we should know better than to know better, right? Maybe culture is the treat of not having to wonder whether or not we really do.