In the ongoing debate about whether or not vaccinations should be mandatory (a debate between so-called “anti-vaxxers” and…well, the people who use that label, the latter of which enjoys majority status to a degree that allows them to forego caricature), the ol’ individual-liberty-versus-public-good rhetoric reared its head really quickly. And perhaps that should come as no surprise. After all, people engaged in the debate are talking about where personal/parental rights stop and the good of the larger public start and vice versa…aren’t they? That’s certainly the nominal subject of the controversy. But “individual liberty” and “public good” certainly live on an ever-sliding scale and are employed by different groups with different politics depending on the context.

Take, for instance, this NPR article, whose headline reads, “To Get Parents to Vaccinate Their Kids, Don’t Ask. Just Tell.” It describes a recent study’s “surprising results” when it came to how parents reacted to how their children’s pediatricians broached the topic of vaccinations. Namely, “When doctors assumed parents would be OK with vaccines, they were. More than 70 percent had their child vaccinated. On the other hand, when physicians were more flexible and allowed for discussion, most of the parents — 83 percent — decided against vaccination…When it comes to public health, [the doctor and researcher who led the study] says, ‘shared decision making’ doesn’t make sense.” It’s easy to think of numerous contexts in which this very argument would seem appalling. Many see informed consent as a right rather a privilege, after all. And whether or not inoculations count as medical procedures or interventions surely depends on who’s being asked. Further, there’s no denying that profits and market competition are part of the privatized medical industry in the U.S., vaccines garnering multiple billions of dollars for drug companies. While I’m not at all suggesting that this fact is necessarily good or bad, I am suggesting that the conversation is more complicated than it appears. Imbedded in it are issues of legality, civic autonomy, access, capitalism, gender, race, class…all classifications that help establish a semblance of an “us” and a “them.”

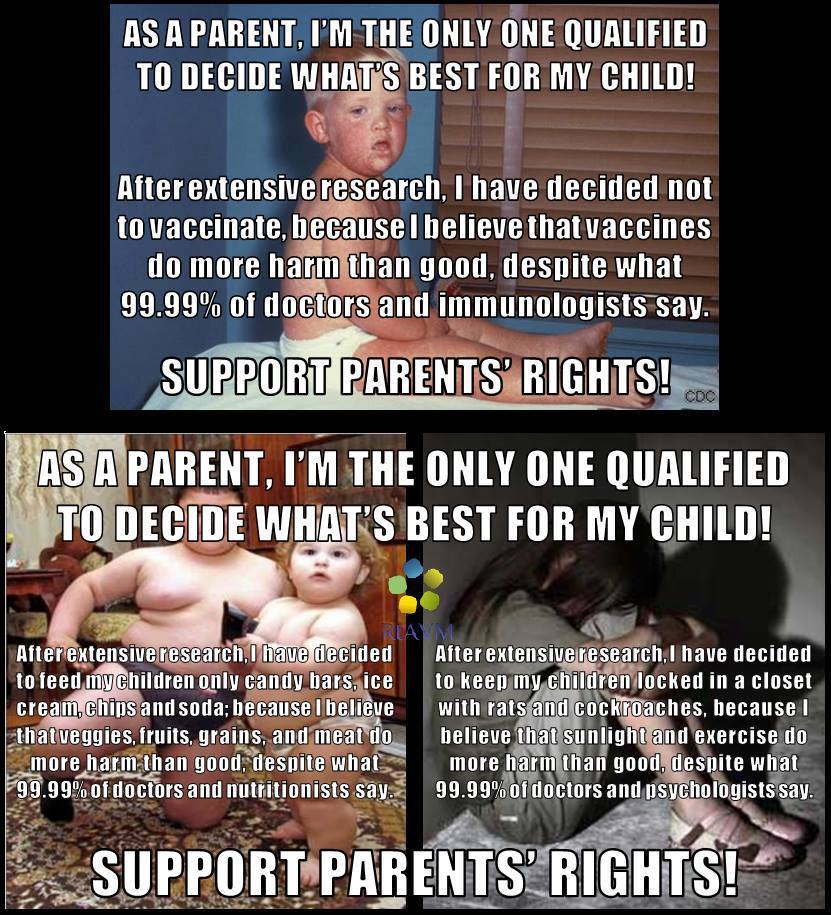

As it stands, however, the debate over vaccines has appeared in social media largely through broad-scale satire and critique. Take the following sets of memes that have been floating around:

What gets me is the degree of sarcasm dripping from phrases like “parents’ rights” and ideas about conventional knowledge surrounding things from vehicular safety to food allergies. Why? Well, for one thing, the quippy zings aimed at social shaming offer a nice example of how social formation works, putting the utter ridiculousness of “them” on display for all of “us” to see, like, and share with just a couple clicks on a keyboard. They demonstrate the way in which a hegemonic majority identifies a social norm and compels others to participate in it, consolidating the seeming naturalness or obviousness of its dominance. Because, “we” do actually enjoy the notion of parents’ rights…don’t we? In certain contexts, sure. But rights and liberties have their limits, as the vaccination debate makes clear.

The second reason I find the sarcasm and easy dismissal present in the social media back-and-forth interesting is that, in the case of the “support parents’ rights” memes, issues of diet and shelter rely on parental autonomy as a starting point, forgetting (or ignoring?) the fact that these issues lie at the nexus of economic, geographical, and often racial marginalization. What a child is or is not able to eat is not always a simple byproduct of a parent’s level of care for that child. Indeed, so much of what the vaccination debate seems to reflect is a couple of groups already enjoying a certain degree of privilege jockeying for power in the hearts and minds of America’s professional class.

An article entitled, “Why Vaccination Refusal Is a White Privilege Problem” is a much better way of addressing the issue, to my mind, if only because it makes apparent the complex ways in which class and race play an integral part in the otherwise simple line of argumentation with which the essay begins—namely, that “Vaccines work.” It notes, for example, that while “undervaccinated” children who have not had all their shots tend to live in underprivileged environments, those kids who go entirely vaccine-free due to parental choice are largely white, from upper-middle-class and educated homes. The prospect of the government getting involved in a mandate holds starkly different consequences for these two demographics. Additionally, the consequences of a sick kid at home also have a different bearing.

The claims that make the issue one of mere choice and arrogance—on either side—ignore such complexities. Advocates of vaccination often casually disregard the ways in which, for example, the scientific medical community is also one driven by corporate interests—a fact that might affect the levels of trust a whole host of folks have or don’t have for their doctors (As Russell McCutcheon’s recent post suggested, science is itself also a discourse). They instead take studies performed by exactly those profit machines as neutral “proof” that vaccinations are safe. Meanwhile, the so-called “anti-vaxxers” (many of whom suggest they don’t want to be labeled as anti-vaccination so much as pro-parental choice) often fail to take stock of the ways in which multiple layers of privilege go into the ability to choose. The “naturalness” of rejecting vaccines is not at all something born in a vacuum in post-industrialized societies.

Thus, the point at which “individual rights and freedoms” should be granted is nothing if not a moving target. This being the case, the lines that are drawn around the personal/private and the public (and the good of each, respectively) are moments of rhetorical framing invoked by those with a certain degree of power who get to choose not only how to frame the debate but also whether to hear the other side at all.

The problem with the article for me: it is about rhetoric and othering, but not about evidence based research, so it should not be titled “informed” dissent, but “nicer rhetoric” dissent.