As those of us who have been witnessing the roller-coaster politics of the United States these past few months can attest, there’s a lot riding on the idea of the president. This may seem truistic, for we all know that presidents are very powerful in great part because they are the megaphone through which a series of legislative platforms is broadcast.

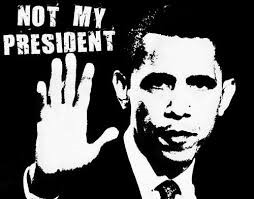

But even more than this, presidents are, for many, the image of the nation-state distilled into a single person. When certain Americans thus claim that Donald Trump is “not my president,” what they are indicating in a very straightforward sense is their rejection of this representative identity even as they wish to retain national ties, for presumably they find inconsistencies between the ways they align their own identities with the nation-state and the president as the national symbol. Of course, we’ve seen that before, most recently in this image:

While many of us fully recognize that the dynamics motivating the groups that renounced Obama were quite different than the dynamics of those who today renounce Trump, these dual symbolic rejections provide some interesting data regarding how national identity is wrought. My interest has lately been piqued by the notion of presidentialism offered by Dana Nelson and Tyler Curtain, who, while providing an explanation for why we care about political sex scandals (a seemingly different, but actually quite similar, topic), simultaneously dissect how the idea of the president tends to work in the consciousness of many Americans.

Nelson and Curtain suggest that a large number of Americans embrace undemocratic attitudes even though the nation is logistically structured as a democracy; examples of this include the cultural disdain that exists over things like peaceful protests (a very basic democratic act) and the relatively low voter turnouts that we frequently see. An actual reversal of democracy occurs, they suggest, when we instill so much of our sense of “the nation” into a single figure — the president — but in so doing fail to see ourselves as being agents of that very nation.

This explains the tremendous scale of the Clinton sex scandal, they note. The issue was never that Clinton lied, for as history reminds us, so have many presidents, about many far graver things, and with little comparative consequence (Donald Trump aside, Reagan’s Iran-Contra scandal is a noteworthy example). Rather, they argue, Americans have typically made quite a spectacle of the sexual indiscretions of presidents over other far more serious matters because they cannot draw a line between their own identity, their national identity, and their president’s identity. Because sexual indiscretion is, to many Americans, a sort of obvious moral violation, it functions as a clear and simple source of anger much more easily accessible than the more complicated policy maneuvers that are actually a part of presidents’ jobs. This is how, they note, a sexual infidelity can be construed to be something akin to the very breakdown of the nation.

Nelson and Curtain argue that the danger of weak citizens is not just an abstract issue because such citizens, in the absence of the sense that their actions matter, are more likely to succumb to the temptation to understand their citizenship in terms of how the political climate makes them feel rather than throw their weight behind a coherent set of policies or facts. Their national contribution thus becomes a reactionary emotional response that is far more dramatic and dichotomous than the reality of the situation may demand, they suggest. One might extrapolate from this model that citizens with a weak understanding of democracy believe it is only working properly when the nation-state looks precisely as they individually wish it to appear — it is a “good democracy” to the degree that its representatives look like how they idealize themselves.

While Nelson and Curtain’s main focus is, again, on the weight given to sex scandals, what I believe that they help solidify is the very close connection between emotion and citizenship. Rather than situate their model of presidentialism as a phenomenon limited to certain times and places, I am more prone to adopt Michael Cobb’s observation that the word “politics” might be best functionally defined as a stance inspired by a set of relatively inchoate feelings that are catalyzed and evoked by certain national symbols. For no matter who the president legally is, perhaps those of us interested in politics and identity construction should spend more time talking about the emotions that such leaders evoke rather than the policies they endorse.

Photo credits: http://www.afro.com/not-my-president-trump-denounced-in-protests-across-us/ ; freerepublic.com