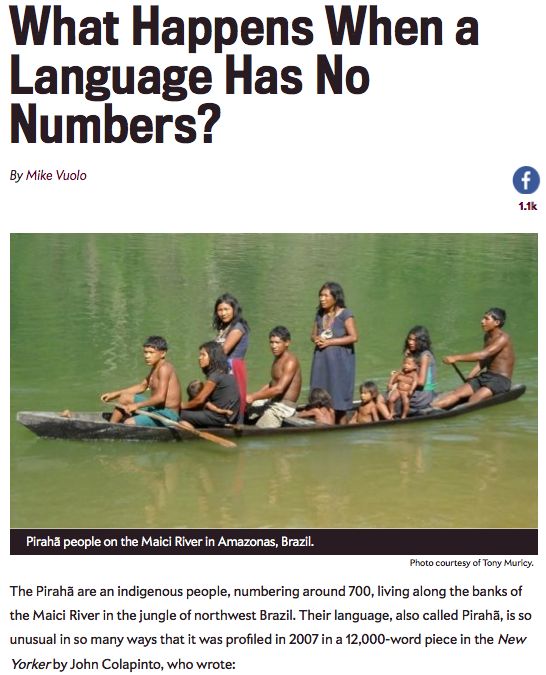

Did you see this recent article at slate.com? I think it’s fascinating — why? Well, not because of the proverbial tribe that’s been found in deepest, darkest wherever, but because of the manner in which the article itself so nicely brings to light the (likely inevitable) problems associated with coming to know anything about the world around us. For in a piece on a group of people who apparently have no numbers in their language system (or at least an inability to think of quantities larger than a few) we see a whole bunch of numbers used by the article’s author to itemize big facts. There’s around 700 of these people, we’re told; we first learned about them in 2007, in a magazine article that was — count ’em! — 12,000 words in length.

Did you see this recent article at slate.com? I think it’s fascinating — why? Well, not because of the proverbial tribe that’s been found in deepest, darkest wherever, but because of the manner in which the article itself so nicely brings to light the (likely inevitable) problems associated with coming to know anything about the world around us. For in a piece on a group of people who apparently have no numbers in their language system (or at least an inability to think of quantities larger than a few) we see a whole bunch of numbers used by the article’s author to itemize big facts. There’s around 700 of these people, we’re told; we first learned about them in 2007, in a magazine article that was — count ’em! — 12,000 words in length.

My point? Unless we privilege our language system as if it is in sync with reality itself — as happens so often, when we start talking about facts — one can’t help but see this story as a moment when two no less local systems bump into each other (something I’m thinking from my position within one of them, of course — how crazy is that?). For our ability to “think itemized quantity” is so self-evident to us that we’re perplexed by how they get along without it — the “it” here is taken as a fact of nature and not some quirky acquisition that we happen to have, of course. That is, why isn’t the article on how peculiar it is that other language systems even have numbers?

Of course we have no choice but to use local assumptions and concepts and curiosities in coming to know those we take to be our others but we too often make the mistake of failing to see these assumptions and concepts and curiosities as our tools. Instead, we (especially if we happen to be in dominant groups) speak loudly and slowly and say such things as “How do you say ‘religion’ in your language?” — as if the fact that we happen to divide up and name the world in this or that way necessarily has some corresponding dance partner in all human systems.

Whether hubris or laziness accounts for this, it’s worth mulling over that a change in attitude toward owning our assumptions and concepts and curiosities might be the first step in doing any sort of interesting work on this thing we’re calling identification.

In the U.S. today is Martin Luther King Day, a federal holiday established in 1986 to commemorate the life and achievements of the noted civil rights leader who was tragically assassinated outside his motel room in Memphis in 1968.

In the U.S. today is Martin Luther King Day, a federal holiday established in 1986 to commemorate the life and achievements of the noted civil rights leader who was tragically assassinated outside his motel room in Memphis in 1968.

Did you see this recent article at

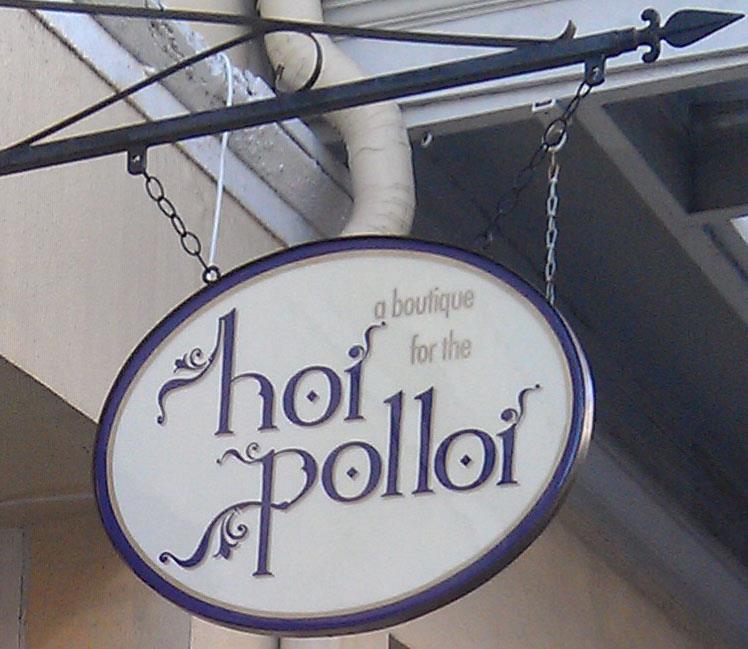

Did you see this recent article at  As a native Greek speaker, the words in English that give me most trouble—especially when I find myself at various conferences or lectures in North America that involve, in some way or another, the use of Ancient Greek—is the pronunciation of those words. I admit that I can’t resist the temptation of correction for example whenever I hear Thucydides (pronounced: Thu-si-di-dees) instead of Θουκυδίδης (pronounced: Thu-ky-theē-thees). But once I found myself in an awkward position where context made the text if not unrecognizable but certainly irrelevant.

As a native Greek speaker, the words in English that give me most trouble—especially when I find myself at various conferences or lectures in North America that involve, in some way or another, the use of Ancient Greek—is the pronunciation of those words. I admit that I can’t resist the temptation of correction for example whenever I hear Thucydides (pronounced: Thu-si-di-dees) instead of Θουκυδίδης (pronounced: Thu-ky-theē-thees). But once I found myself in an awkward position where context made the text if not unrecognizable but certainly irrelevant.