“Making Football English” (Part I of this two-part series) addressed the ways in which Julian Fellowes’s The English Game narrativizes the origins of football (or soccer, for those of us in the U.S.) as distinctly English despite the Scottish influence on the English game. As discussed in part one:

Football historian and The English Game consultant Andy Mitchell tells The Telegraph‘s Paul Kendall, “The Scottish game was far more effective than the English game at this time. The English version … was more like rugby.” Paul Kendall continues: where the English teams “would just dribble in a pack and try and force a goal through brute strength,” the Scottish teams “developed a way of making space and passing the ball … playing the game as we understand it today.” The series concludes with this title frame:

Apart from Fellowes’s endeavor to portray football as distinctly English, I found this concluding title slide in the final episode particularly intriguing. The so-called “English game,” pioneered by Scottish professionals, is presented not only as being distinctly English, but also as the standard for modern football around the globe. Continue reading “Universalizing “English” Football, Part II”

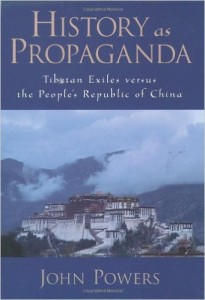

In History as Propaganda: Tibetan Exiles versus the People’s Republic of China, John Powers surveys a wide variety of histories of Tibet, written by Tibetan, Chinese, and western (i.e., American or European) authors. The story of the relations between China and Tibet — is Tibet an independent state or merely a small part of China’s empire? — can be told in many different ways, depending on the interests or agenda of the author spinning the narrative. Of particular interest to me is how Powers notes the normative vocabulary of the historians he surveys. The authors tend to systematically use normative nouns and adjectives — with positive and negative valuations attached to them — in their narratives. See the following two tables:

In History as Propaganda: Tibetan Exiles versus the People’s Republic of China, John Powers surveys a wide variety of histories of Tibet, written by Tibetan, Chinese, and western (i.e., American or European) authors. The story of the relations between China and Tibet — is Tibet an independent state or merely a small part of China’s empire? — can be told in many different ways, depending on the interests or agenda of the author spinning the narrative. Of particular interest to me is how Powers notes the normative vocabulary of the historians he surveys. The authors tend to systematically use normative nouns and adjectives — with positive and negative valuations attached to them — in their narratives. See the following two tables:

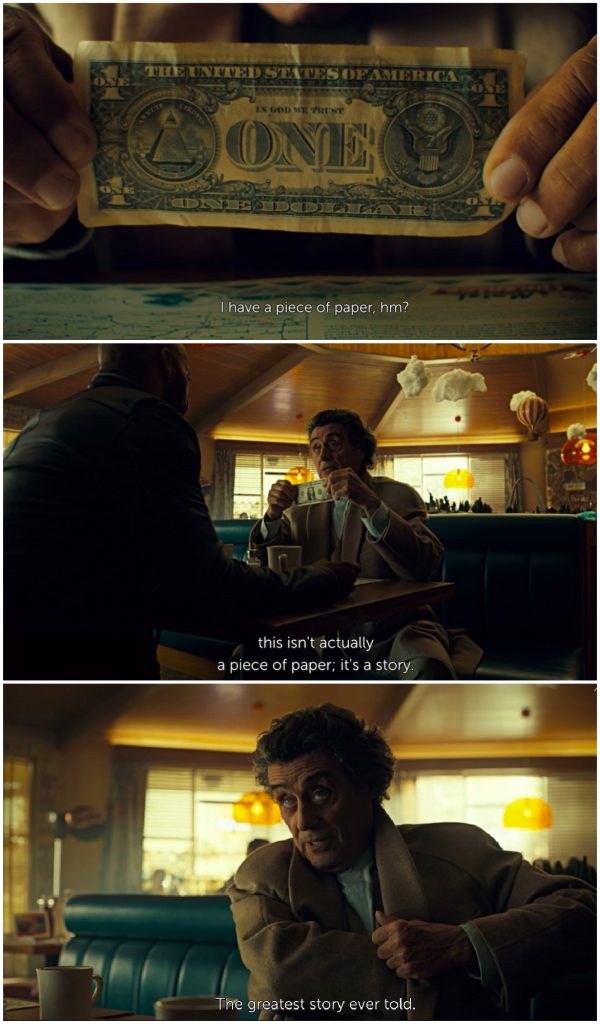

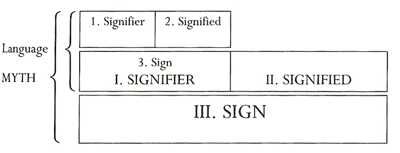

I remember standing in the checkout line at the campus bookstore with my copy of Roland Barthes Mythologies. I admit that I was suspicious of any book supposedly so profound that was also so small. Its size is deceiving just as much as its structure is unique: the first part of Mythologies is comprised of a series of short essays that provide the pop-culture exemplars of Barthes’ theory on how mythmaking operates (covering everything from food to clothing to politics), while the latter half is comprised of a theoretical essay – entitled simply “Myth Today” – that more overtly addresses the workings of this type of semiotic turn. Barthes rejected common definitions of myth that equate it with “falsehood” or “the stories that dead people believed.” Rather, Barthes understood myth as an absolutely ubiquitous process that involves the transformation of “history into nature,” or, put differently, the manner in which otherwise constructed things are made to appear natural or inevitable.

I remember standing in the checkout line at the campus bookstore with my copy of Roland Barthes Mythologies. I admit that I was suspicious of any book supposedly so profound that was also so small. Its size is deceiving just as much as its structure is unique: the first part of Mythologies is comprised of a series of short essays that provide the pop-culture exemplars of Barthes’ theory on how mythmaking operates (covering everything from food to clothing to politics), while the latter half is comprised of a theoretical essay – entitled simply “Myth Today” – that more overtly addresses the workings of this type of semiotic turn. Barthes rejected common definitions of myth that equate it with “falsehood” or “the stories that dead people believed.” Rather, Barthes understood myth as an absolutely ubiquitous process that involves the transformation of “history into nature,” or, put differently, the manner in which otherwise constructed things are made to appear natural or inevitable.