“Making Football English” (Part I of this two-part series) addressed the ways in which Julian Fellowes’s The English Game narrativizes the origins of football (or soccer, for those of us in the U.S.) as distinctly English despite the Scottish influence on the English game. As discussed in part one:

Football historian and The English Game consultant Andy Mitchell tells The Telegraph‘s Paul Kendall, “The Scottish game was far more effective than the English game at this time. The English version … was more like rugby.” Paul Kendall continues: where the English teams “would just dribble in a pack and try and force a goal through brute strength,” the Scottish teams “developed a way of making space and passing the ball … playing the game as we understand it today.” The series concludes with this title frame:

Apart from Fellowes’s endeavor to portray football as distinctly English, I found this concluding title slide in the final episode particularly intriguing. The so-called “English game,” pioneered by Scottish professionals, is presented not only as being distinctly English, but also as the standard for modern football around the globe.

On the one hand, such a claim is not unreasonable. The creation of The Football Association (FA) in 1863 was the first English codification of a regionally varied game into an official “sport.” But depending on one’s interests and perspective, football could have a number of origins.

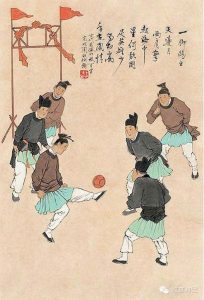

Unlike what this title frame seems to suggest, versions of football have existed around the world since the 3rd-2nd century BCE. In fact, FIFA (see more below) officially recognizes the Chinese game cuju (pictured on the left), which originated during the Han dynasty, as the earliest form of football. Cuju was a competitive, standardized game that emphasized technique and dexterity with the ball (not unlike the Scottish method). Similarly, Kemari, a Japanese version of cuju, emerged in 644 CE. The Roman harpastum and its Greek influence, episkyros (2nd and 3rd centuries CE), are also early forms of football. The modern Italian term for football, calcio, derives from a 16th century calcio fiorentino, a Florentine football-like game. Well before the 1600s, Lenape Indians played Pahsahëmon, a structured football-like game, and the indigenous Australian Marn Grook was an early foundation of Australian rules football and its subsequent Melbourne Football Club. The list goes on…

Unlike what this title frame seems to suggest, versions of football have existed around the world since the 3rd-2nd century BCE. In fact, FIFA (see more below) officially recognizes the Chinese game cuju (pictured on the left), which originated during the Han dynasty, as the earliest form of football. Cuju was a competitive, standardized game that emphasized technique and dexterity with the ball (not unlike the Scottish method). Similarly, Kemari, a Japanese version of cuju, emerged in 644 CE. The Roman harpastum and its Greek influence, episkyros (2nd and 3rd centuries CE), are also early forms of football. The modern Italian term for football, calcio, derives from a 16th century calcio fiorentino, a Florentine football-like game. Well before the 1600s, Lenape Indians played Pahsahëmon, a structured football-like game, and the indigenous Australian Marn Grook was an early foundation of Australian rules football and its subsequent Melbourne Football Club. The list goes on…

Given the variety of historical influences, how does one determine which earlier game is the most similar or the original?

Though the Football Association standardized the game in the United Kingdom and held international games (within the UK) starting in 1883, the global impact was slower to develop. In 1904, FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association), the current international governing body of football, was founded to oversee international competitions for Belgium, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. Though England joined FIFA in 1906, they did not participate until 1950. (Not unlike the Football Association, FIFA has its own controversial history. Learn more about it from John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight here and here.)

Though the Football Association standardized the game in the United Kingdom and held international games (within the UK) starting in 1883, the global impact was slower to develop. In 1904, FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association), the current international governing body of football, was founded to oversee international competitions for Belgium, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. Though England joined FIFA in 1906, they did not participate until 1950. (Not unlike the Football Association, FIFA has its own controversial history. Learn more about it from John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight here and here.)

Despite the narrative that Julian Fellowes develops in The English Game about football being distinctly English, we can see that there’s a lot more going on in the world of soccer outside of England. While on the one hand, that may seem like an obvious assertion, let’s consider Fellowes’s narrative in relation to that global context to which he alludes. As Jonathan Wilson argues in The Guardian:

The English game became the Austrian game, the Hungarian game, the Argentinian game and, particularly, the Uruguayan game. It became everybody’s game, interpreted differently by every culture that embraced it. … One of the fascinations of football is that it is simultaneously intensely local and utterly globalised, with all the tensions that brings.

Though English football clubs and England’s national football team, The Three Lions, are widely known and supported, England has had little success on the global stage apart from the 1966 FIFA World Cup and the 2009 and 1984 UEFA Women’s Euro Cup. The varied interpretations and tensions to which Wilson alludes came to a head in that 1966 World Cup quarter-final between England and Argentina, which was regarded more as an “international incident.” There were discrepancies in how different rules, such as off-sides and tackles, were understood, and the referees appeared to clearly favor the England national team.

The 1966 World Cup quarter-finals is not unlike the 1879 FA Cup in some ways. In both instances, England and the Old Etonians, respectively, asserted their rules and understanding of the game only to be met with a great deal of pushback. Furthermore, both the local and global differences Wilson discusses are managed to promote an overall sense of unity or identity.

So what are we to make of Fellowes’s attempt to center England in this broader, complicated history?

Despite being a long-time soccer fan myself, I admit that I had no knowledge of the Football Association, the Old Etonians, or concerns about professional players. Instead, my understanding of football history revolved around FIFA. As The English Game actor Edward Holcroft (Arthur Kinnaird) asserts:

It’s amazing how little people who are fanatical about football know about how it started, who was influential. They don’t actually know the history of the sport they are so passionate about.

On the one hand, Holcroft is right — I certainly had no knowledge of this, but on the other, Holcroft’s assertion demonstrates my very point. While the “modern game” is clearly influenced by England’s Football Association, the FA’s role, though a crucial turning point, is a small part of that global history. Thus, Fellowes’s attempt to place England at the center of this football narrative both in the United Kingdom and on a global stage is particularly interesting.

Within the context of the show, narrativizing football as distinctly English doesn’t seem too unreasonable so long as one overlooks the ways in which differences were codified and managed (as I discussed in Part I). But when considering “modern” football to be an “English game” on a global stage, one is required to do a bit more legwork in overlooking the historical gaps and prioritizing certain football “facts” over others for that classification to work.

However, this is not a critique of the show. After all, The English Game effectively demonstrates how certain ideas, agendas, and identities are promoted over an array of differences and discrepancies to create a particular narrative. Rather than accepting or negating the history of football or modern football as being inherently English, we might instead consider the narrative process so to see what information is included (or excluded) and what is at stake in this particular retelling.