“Making Football English” (Part I of this two-part series) addressed the ways in which Julian Fellowes’s The English Game narrativizes the origins of football (or soccer, for those of us in the U.S.) as distinctly English despite the Scottish influence on the English game. As discussed in part one:

Football historian and The English Game consultant Andy Mitchell tells The Telegraph‘s Paul Kendall, “The Scottish game was far more effective than the English game at this time. The English version … was more like rugby.” Paul Kendall continues: where the English teams “would just dribble in a pack and try and force a goal through brute strength,” the Scottish teams “developed a way of making space and passing the ball … playing the game as we understand it today.” The series concludes with this title frame:

Apart from Fellowes’s endeavor to portray football as distinctly English, I found this concluding title slide in the final episode particularly intriguing. The so-called “English game,” pioneered by Scottish professionals, is presented not only as being distinctly English, but also as the standard for modern football around the globe. Continue reading “Universalizing “English” Football, Part II”

1. When people ask what you study, what do you tell them?

1. When people ask what you study, what do you tell them?

1. When people ask what you study, what do you tell them?

1. When people ask what you study, what do you tell them? Photo of Animated Triceratops at Universal’s Island of Adventures, Orlando, FL

Photo of Animated Triceratops at Universal’s Island of Adventures, Orlando, FL Photo Copyright Universal Studios, Film Stills: Jurassic Park (1993)

Photo Copyright Universal Studios, Film Stills: Jurassic Park (1993)

Recognizing identifications as narrative constructs or fixed identities organizes the world in particular ways that inform the debate over the

Recognizing identifications as narrative constructs or fixed identities organizes the world in particular ways that inform the debate over the

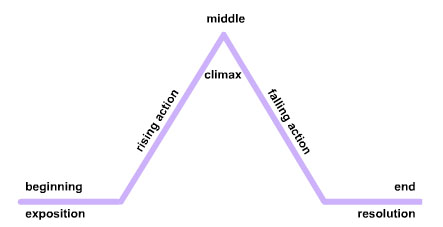

Gun fights, political intrigue, and a race against time. Reading fiction is one activity that provides a little excitement. While I enjoy a range of authors and styles, my favorites are the pulp espionage and legal thrillers from authors like David Baldacci, John Grisham, and Steven Martini. The exciting plot keeps me highly engaged and turning the pages to see how the hero or (sometimes) heroine fight off or outwit the dangerous, enigmatic threat. Like many people, I appreciate a good narrative, and that desire for a manageable, linear plot is not limited to reading novels.

Gun fights, political intrigue, and a race against time. Reading fiction is one activity that provides a little excitement. While I enjoy a range of authors and styles, my favorites are the pulp espionage and legal thrillers from authors like David Baldacci, John Grisham, and Steven Martini. The exciting plot keeps me highly engaged and turning the pages to see how the hero or (sometimes) heroine fight off or outwit the dangerous, enigmatic threat. Like many people, I appreciate a good narrative, and that desire for a manageable, linear plot is not limited to reading novels.