By Stephen S. Bush

Stephen S. Bush is an associate professor of religious studies at Brown University. He is the author of Visions of Religion: Experience, Meaning, and Power, and he is presently working on a book on William James’s political philosophy and philosophy of religion.This guest blog is a response to Craig Martin’s recent post.

In Visions of Religion, I critically engage the three most prominent theoretical approaches to the study of religion in the past hundred or so years, which prioritize respectively experience, meaning, and power. I embrace key insights from all three schools of thought, but I correct them all on important points. I integrate the valuable contributions of each into a theory of religion according to which religion is a matter of social practices.

According to Craig Martin, in my book, I frequently leave off reasoned argumentation. He says I make undefended assertions that have no other basis than how I “feel.” Or perhaps, he says, the problem is not with my personal preferences, it’s with him. He is, he tells us, an outsider to religious studies. I can afford to make undefended assertions, because the rest of the field unquestioningly buys into my assumptions, which are those of the “status quo.” From his vantage point, he can see them as the unexamined prejudices they are. Continue reading “Reply: Reasons and Objectivity in the Study of Religion”

Anyone who knows me knows that I walk my dog early each morning — lately I’m regularly going to a nearby park where, well, Izzy goes regularly as well. But every now and then I change it up a little — variety is the spice of life and all that — and so I park here and we walk there or park over there and then we walk here. Sometimes I park in one of the lots but other times I pull over off the small loop of a road and park on the grassy shoulder.

Anyone who knows me knows that I walk my dog early each morning — lately I’m regularly going to a nearby park where, well, Izzy goes regularly as well. But every now and then I change it up a little — variety is the spice of life and all that — and so I park here and we walk there or park over there and then we walk here. Sometimes I park in one of the lots but other times I pull over off the small loop of a road and park on the grassy shoulder.  I’ve written before about the curious relationship between form and content — and the manner in which (despite how we usually think about it) meaning is the product of the former.

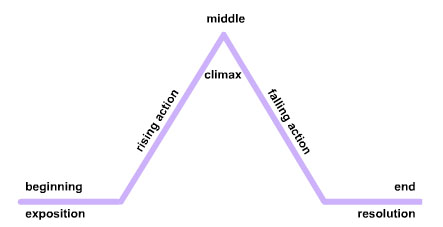

I’ve written before about the curious relationship between form and content — and the manner in which (despite how we usually think about it) meaning is the product of the former. Gun fights, political intrigue, and a race against time. Reading fiction is one activity that provides a little excitement. While I enjoy a range of authors and styles, my favorites are the pulp espionage and legal thrillers from authors like David Baldacci, John Grisham, and Steven Martini. The exciting plot keeps me highly engaged and turning the pages to see how the hero or (sometimes) heroine fight off or outwit the dangerous, enigmatic threat. Like many people, I appreciate a good narrative, and that desire for a manageable, linear plot is not limited to reading novels.

Gun fights, political intrigue, and a race against time. Reading fiction is one activity that provides a little excitement. While I enjoy a range of authors and styles, my favorites are the pulp espionage and legal thrillers from authors like David Baldacci, John Grisham, and Steven Martini. The exciting plot keeps me highly engaged and turning the pages to see how the hero or (sometimes) heroine fight off or outwit the dangerous, enigmatic threat. Like many people, I appreciate a good narrative, and that desire for a manageable, linear plot is not limited to reading novels.

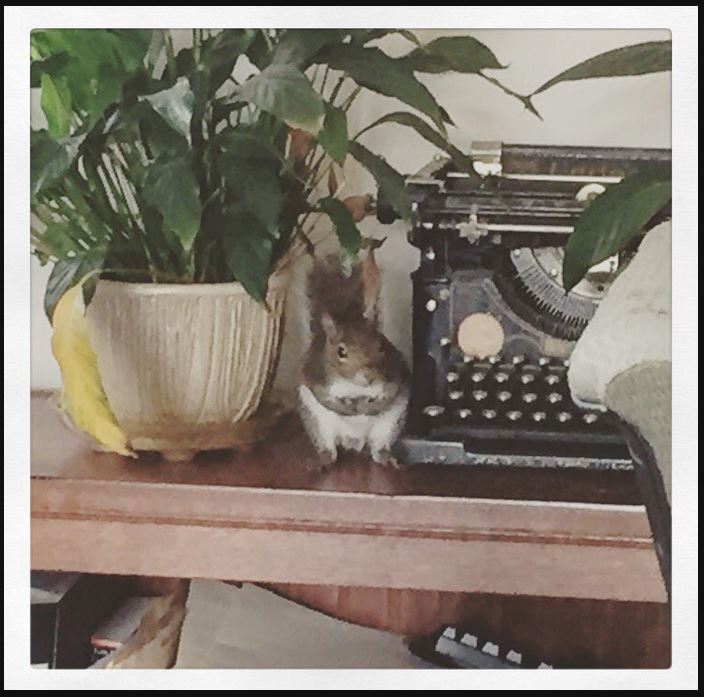

I went to lunch the other day and, unknowingly, locked a squirrel in my office.

I went to lunch the other day and, unknowingly, locked a squirrel in my office.  Do you remember when a few people suggested that Obama would crown himself dictator, run for a third term, confiscate all of the guns, etc., etc.? Now that the primaries and caucuses for the election of his successor are virtually complete, those fears seem to have dissipated, replaced with new fears, of course. And stoking fear happens across the political spectrum. Someone is taking away our opportunities (whether identified as immigrants or the superrich). Someone is trying to take away our vote (whether a particular party or campaign, SuperPACs or legislators through redistricting and new voting requirements). If the other party (whichever is other within the conversation) comes to power, they will take away vital rights (reproductive choice, second amendment, privacy, etc.). We are repeatedly told to be afraid. With all the talk of fear, it appears that the freedoms and quality of life in the United States hang by a thread.

Do you remember when a few people suggested that Obama would crown himself dictator, run for a third term, confiscate all of the guns, etc., etc.? Now that the primaries and caucuses for the election of his successor are virtually complete, those fears seem to have dissipated, replaced with new fears, of course. And stoking fear happens across the political spectrum. Someone is taking away our opportunities (whether identified as immigrants or the superrich). Someone is trying to take away our vote (whether a particular party or campaign, SuperPACs or legislators through redistricting and new voting requirements). If the other party (whichever is other within the conversation) comes to power, they will take away vital rights (reproductive choice, second amendment, privacy, etc.). We are repeatedly told to be afraid. With all the talk of fear, it appears that the freedoms and quality of life in the United States hang by a thread.