“The winners write the history” is an easy way to highlight that those who have power are the ones who control how history is told. But this adage needs a bit more nuance, as sometimes those who lose end up on the winning side anyway. In the case of the American Civil War, the accounts that we tell in the United States too often legitimize the Confederacy. While some descriptions receive significant critique, such as Secretary Ben Carson describing slaves as “immigrants”, typical accounts are more subtle, hardly noticed by many. For example, narratives seldom refer to the actions of the Confederacy as treasonous, even though Andrew Johnson’s 1868 pardon given to those who fought for the Confederacy describes the rebellion as an act of treason.

A recent Smithsonian article presents various examples to make this point, noting how the rhetoric about the Civil War treats the Confederacy as an “equal entity” to the Union, even though foreign governments did not recognize the Confederacy as a nation. This treatment is evident in the language used to describe the conflict and Confederates. In the article, Christopher Wilson writes,

The language we turn to in describing the war, from speaking of compromise and plantations, to characterizing the struggle as the North versus the South, or referring to Robert E. Lee as a General, can lend legitimacy to the violent, hateful and treasonous southern rebellion that tore the nation apart from 1861 to 1865.

Describing Lee according to his rank in the Confederate Army, rather than his rank in the US Army before the rebellion (Colonel), accepts the Confederacy as an equally legitimate military, even though it was not authorized by a recognized nation-state. The suggestions from various historians that the plantation economy was, more accurately, a slave labor camp economy or that the Compromise of 1850 was an appeasement illustrate the power of these word choices. The terms that people use to describe things are selective and generate particular connotations that influence how we view the past and the current world.

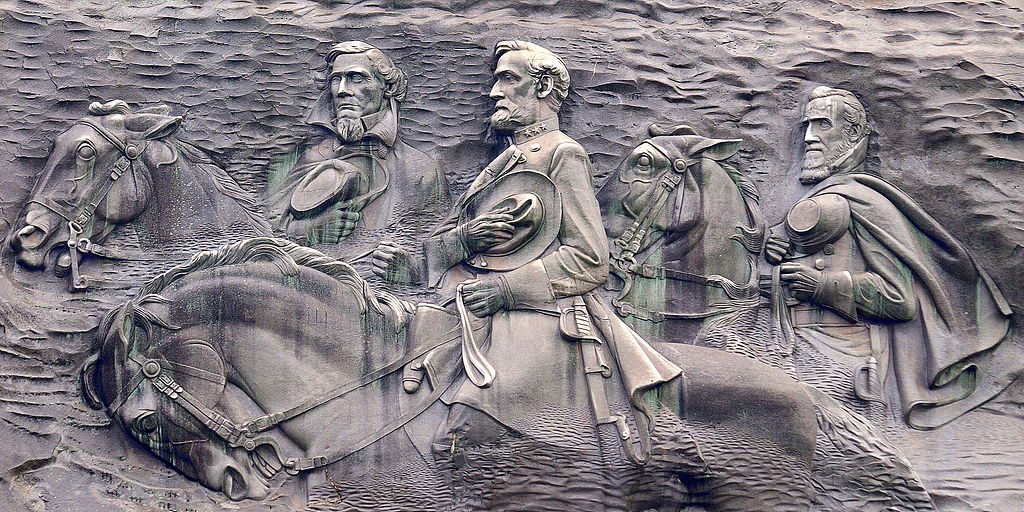

Identifying the legitimation of the Confederacy through these strategic language choices raises a further question, why did the defeat of the Confederacy lead to the Confederacy winning the struggle over the historical narrative in significant ways (though perhaps not completely)? Johnson’s pardon proclamation for Confederate supporters declared its goal “to secure permanent peace, order, and prosperity throughout the land, and to renew and fully restore confidence and fraternal feeling among the whole people, and their respect for and attachment to the National Government, designed by its patriotic founders for the general good.” Reconciliation for the national good often requires appeasement of the feelings of the defeated, but even more seems to be at play here. The euphemisms and respectful tone towards the Confederacy in the historical narratives, which arise from the concern for reconciliation in the North, suggests a desire to appease white southerners, generating more concern among national leaders for the feelings of white southerners than those of former slaves. Just as many of the monuments glorifying Confederate leaders arise when Jim Crow laws were being enacted and when racial discrimination came to prominence during the Civil Rights Movement (thus reflecting a concern for maintaining white dominance), the language commonly used in narratives about the Civil War reflect a greater interest in maintaining the dominance of white Americans by relegating the experiences of slavery and racial discrimination to the realm of euphemism and marginalized positions. The winners who write the history were not really those who fought for the United States (euphemistically the Union) over those who attempted to destroy the Untied States (euphemistically the Confederacy). From the perspective of the historical narrative, the winners were those who have maintained power in the North and the South (for much of the 20th century, almost exclusively whites) over those who have frequently been marginalized and disenfranchised (predominately people of color).

Photo credit: Stone Mountain Carving by Jim Bowen [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons