Here in the U.S. there’s an ad campaign for Snickers chocolate bars, in which hungry people turn back into themselves only once they have a snack. Continue reading ““You’re Not You When You’re Hungry””

Here in the U.S. there’s an ad campaign for Snickers chocolate bars, in which hungry people turn back into themselves only once they have a snack. Continue reading ““You’re Not You When You’re Hungry””

First Impressions #21: Leslie Dorrough Smith

Marginalia recently posted this interview of the Edge’s own Leslie Dorrough Smith talking with Art Remillard (Avila University) on her recently released book Righteous Rhetoric.

Click here to listen to the interview…

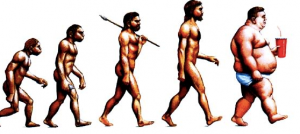

Caveman Grub: The Identity Politics of Paleo

After one of my kids was diagnosed with a health condition last year, our doctor recommended that our whole family radically change what (we believed) was our otherwise healthy diet and embrace a way of eating that has popularly become known as the Paleo diet. “Paleo” is a term used to reference what many say were the eating habits of Paleolithic-era humans (more on that in a moment). This approach to food emphasizes the consumption of lean meats, veggies, fruits, and nuts (all things that one would hunt and/or gather, so the story goes) at the same time that it eschews grains, dairy, legumes, and all refined, processed, or artificial foods.

A little internet reading could easily convince the novitiate that there is a Paleo god looking to strike dead those who stray from its parameters, for there are a myriad of Paleo folks out there who argue vehemently about what constitutes the “truest” Paleo lifestyle. Despite their differences, the philosophical tie that unites most Paleo adherents is the sense that “eating like a caveman” is the most “natural” and “authentic” approach to food possible, one closest to how our bodies are “designed” to be fed. Good health is often promised as the result of firm adherence to the philosophy, and this is the rationale Paleophiles have long provided for why so many people experience a multitude of positive health benefits when they follow it. Continue reading “Caveman Grub: The Identity Politics of Paleo”

You Are What You Read, with Leslie Smith (Part 1)

For a new Culture on the Edge series “You Are What You Read” we’re asking each member to answer a series of questions about books—either academic or non-academic—that have been important or influential on us.

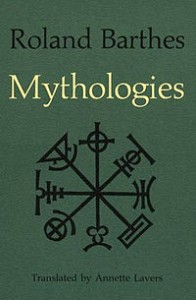

1. Name a book you read early on that shaped the trajectory of your career.

I remember standing in the checkout line at the campus bookstore with my copy of Roland Barthes Mythologies. I admit that I was suspicious of any book supposedly so profound that was also so small. Its size is deceiving just as much as its structure is unique: the first part of Mythologies is comprised of a series of short essays that provide the pop-culture exemplars of Barthes’ theory on how mythmaking operates (covering everything from food to clothing to politics), while the latter half is comprised of a theoretical essay – entitled simply “Myth Today” – that more overtly addresses the workings of this type of semiotic turn. Barthes rejected common definitions of myth that equate it with “falsehood” or “the stories that dead people believed.” Rather, Barthes understood myth as an absolutely ubiquitous process that involves the transformation of “history into nature,” or, put differently, the manner in which otherwise constructed things are made to appear natural or inevitable. Continue reading “You Are What You Read, with Leslie Smith (Part 1)”

I remember standing in the checkout line at the campus bookstore with my copy of Roland Barthes Mythologies. I admit that I was suspicious of any book supposedly so profound that was also so small. Its size is deceiving just as much as its structure is unique: the first part of Mythologies is comprised of a series of short essays that provide the pop-culture exemplars of Barthes’ theory on how mythmaking operates (covering everything from food to clothing to politics), while the latter half is comprised of a theoretical essay – entitled simply “Myth Today” – that more overtly addresses the workings of this type of semiotic turn. Barthes rejected common definitions of myth that equate it with “falsehood” or “the stories that dead people believed.” Rather, Barthes understood myth as an absolutely ubiquitous process that involves the transformation of “history into nature,” or, put differently, the manner in which otherwise constructed things are made to appear natural or inevitable. Continue reading “You Are What You Read, with Leslie Smith (Part 1)”

When Choirs Preach to Themselves

I was struck last week by this article from the New York Times, which (serendipitiously) corresponds to a classroom experience that I often have. In the article, author Maria Konnikova describes the role that facts play in belief formation. Konnikova is documenting what many other psychologists have also noted: many of our strongly-held beliefs are formed not because they are particularly logical or backed with hard data, but emerge only to the degree that they reinforce ideas that we already hold. What this means is that we tend to gravitate towards the familiar rather than the factual.

There are many reasons why people reject sound data, and Konnikova mentions briefly that mistrust of authority is a predominant reason. But I think there might be something even more fundamental going on here, something I often witness in my own students’ responses when I have them do a very simple exercise. Continue reading “When Choirs Preach to Themselves”

Why, When I was a Kid…

The other day I was cruising around the web reading old New York Times pieces and came across one entitled “Does Religion Oppress Women.” As with many things on the web (e.g., the banana slicer for sale at amazom.com), the comments section is the best part. For example:

The other day I was cruising around the web reading old New York Times pieces and came across one entitled “Does Religion Oppress Women.” As with many things on the web (e.g., the banana slicer for sale at amazom.com), the comments section is the best part. For example:

kaybee’s comment stood out for me because it nicely represents a commonplace strategy — a strategy at home within the academy no less than in comments on the web — of positing a pristine originary moment that, once expressed or shared, is only later corrupted and polluted. It’s a model not unlike the telephone game (problematically known as “Chinese whispers” earlier on), which judges the contemporary against the pure source, and one that we find in the U.S. supreme court (when a justices measure current behaviors by the standard of what the writers of the Constitution intended) as well as in the study of etymology itself (whose own etymology denotes studying the true meaning of a word). Continue reading “Why, When I was a Kid…”

kaybee’s comment stood out for me because it nicely represents a commonplace strategy — a strategy at home within the academy no less than in comments on the web — of positing a pristine originary moment that, once expressed or shared, is only later corrupted and polluted. It’s a model not unlike the telephone game (problematically known as “Chinese whispers” earlier on), which judges the contemporary against the pure source, and one that we find in the U.S. supreme court (when a justices measure current behaviors by the standard of what the writers of the Constitution intended) as well as in the study of etymology itself (whose own etymology denotes studying the true meaning of a word). Continue reading “Why, When I was a Kid…”

You Are What You Read, with Russell McCutcheon (Part 2)

For a new Culture on the Edge series “You Are What You Read” we’re asking each member to answer a series of questions about books—either academic or non-academic—that have been important or influential on us.

2. Name one of your favorite theory books.

With my earlier career in mind, it would have to be Terry Eagleton’s Literary Theory: An Introduction (1983), though I have the 1989 edition, which I bought in Toronto in January of 1991 (evident, again, from my dated front inscription). It too was a book recommended to me by Neil McMullin, and it makes sense to be dated a little later than my copy of The Sacred and the Profane, for (at least as I remember it now), I wasn’t dipping into theory until I’d confirmed that there was a project of some sort to be done on the widespread essentialist understanding of religion as socio-politically and historically autonomous. So having decided there was indeed a project here, at least as applied to Eliade’s one book, the challenge was to start reading as much of his work as I could, and to then be able to make the case that his work exemplified (though it didn’t necessary cause) much wider trends evident throughout the field, and then to come up with a set of tools to critique this approach and identify its practical implications. And that’s where Eagleton’s work came in—helping me to make the shift from seeing words and texts as inherently meaningful, as being in reference to objects in the world that we were talking about, to identifying the apparatuses necessary to signify these scribbles that we call letters, to read them as meaningful—to, as I might now say, operationalize them. Given that I was a sciences undergrad, I’d only taken the virtually mandatory first year English Lit course, with my thick two volume Norton anthology, so reading literary theory, much less the social theory I later came to read, was completely alien to me. Continue reading “You Are What You Read, with Russell McCutcheon (Part 2)”

With my earlier career in mind, it would have to be Terry Eagleton’s Literary Theory: An Introduction (1983), though I have the 1989 edition, which I bought in Toronto in January of 1991 (evident, again, from my dated front inscription). It too was a book recommended to me by Neil McMullin, and it makes sense to be dated a little later than my copy of The Sacred and the Profane, for (at least as I remember it now), I wasn’t dipping into theory until I’d confirmed that there was a project of some sort to be done on the widespread essentialist understanding of religion as socio-politically and historically autonomous. So having decided there was indeed a project here, at least as applied to Eliade’s one book, the challenge was to start reading as much of his work as I could, and to then be able to make the case that his work exemplified (though it didn’t necessary cause) much wider trends evident throughout the field, and then to come up with a set of tools to critique this approach and identify its practical implications. And that’s where Eagleton’s work came in—helping me to make the shift from seeing words and texts as inherently meaningful, as being in reference to objects in the world that we were talking about, to identifying the apparatuses necessary to signify these scribbles that we call letters, to read them as meaningful—to, as I might now say, operationalize them. Given that I was a sciences undergrad, I’d only taken the virtually mandatory first year English Lit course, with my thick two volume Norton anthology, so reading literary theory, much less the social theory I later came to read, was completely alien to me. Continue reading “You Are What You Read, with Russell McCutcheon (Part 2)”

Identifying Identity with Craig Martin

“Identifying Identity” offers a series of responses from members of Culture on the Edge to the following claim made by Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg:

The End of the (Face)Book and the Beginning of Writing

In Of Grammatology, Jacques Derrida deconstructs the metaphysics of presence: differance — nothing in itself — is the constitutive negativity that makes presence possible yet impossible. No thing can ever be present to itself or to another without the insertion of differance, the gap that makes hearing or vision — or any form of knowing — possible in the first place, and that gap makes full presence a priori impossible.

Zuckerberg’s comments on identity strike me as a defense of the metaphysics of presence: the self with integrity — the integral self — must make itself fully present to itself and to others. To hide part of the self is, apparently, to lack integrity. In this Zuckerberg is correct, except that that very lack of integrity is what makes selves possible in the first place; unless we except our selves from our selves, we cannot be present to another at all. Every manifestation of a self on Facebook is always already constituted by differance; every click is a dislocation of unity. The loss of integrity is what makes the self visible. There is nothing outside the text —this process of textuality, iterability, and writing is what weaves selves into existence in the first place (although, for Derrida, this means that there is no “in the first place”). Continue reading “Identifying Identity with Craig Martin”

Identifying Identity with Monica Miller

“Identifying Identity” offers a series of responses from members of Culture on the Edge to the following claim made by Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg:

Zimmer’s critique of Zuckerberg’s disingenuous claim that somehow having more than one identity equates to a lack of integrity is spot on. In fact, Zuckerberg’s claim is laughable, for we analysts know all too well that identities are never singular nor static – rather – always fluid over time and space and most importantly perhaps, they are co-constitutive and contingent, never of their own complete making. This thinking, about identity and identities is well marked by the work we do here at The Edge insofar as we take seriously Bayart’s assertion that “there is no such thing as identity, only operational acts of identification.” With that in mind, and pushing further the constructed nature of and the tactics and strategies that make identities possible, the social actor does not have complete control over how their identities are made – and more so – how such identities are read and represented, especially as they are mediated technologically in and through online formats like social media. Continue reading “Identifying Identity with Monica Miller”

Identifying Identity with Merinda Simmons

“Identifying Identity” offers a series of responses from members of Culture on the Edge to the following claim made by Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg:

When I signed up for a Facebook account (I held out for a while, not really understanding the potential for something called a “social network” that combined two things to which I’m not particularly suited: technology and, well, social networking), I remember someone telling me in an attempt to explain the difference between how one presents oneself on Facebook vs. Myspace, “Facebook is like a posed photo. Myspace is more like a candid snapshot.” My friend was trying to help me get a sense of the format and layout of the two sites, how they would present the information and images I post to the cyberworld around me. His ultimate point in response to my privacy paranoias? Sure I had control, but I didn’t have control. I’ve been thinking about that conversation ever since the controversy over Facebook’s “real-name policy” flared up. Continue reading “Identifying Identity with Merinda Simmons”