This semester I’m teaching a course on Religion & Gender, and one of the books I use is Julie Ingersoll’s Evangelical Christian Women. Ingersoll wrote the book in part as a response to the scholars who have argued that some evangelical Christian women claim to feel “empowered” by complementarianism and the separate spheres discourse (i.e., the discourse that separates out public from private life and relegates men to the former and women to the latter). Ingersoll allows that that might be true for some women in evangelical communities, but that other evangelical women report finding evangelical gender ideology oppressive and discriminatory — and she supports the claim with ample evidence gathered through interviews with evangelical women.

One of the claims of the book is that the contestation of gender is central to evangelicalism, or what we might call the evangelical habitus. That’s why, according to Ingersoll, that debates over whether women can be ministers, leaders, or teachers, as well as the debate over gay rights, generate so much heat within the evangelical subculture.

In the chapter “The Power of Subtle Arrangements and Little Things,” Ingersoll notes that practically everything in evangelical communities is gendered in some way or another. Her examples include the following:

- small groups or prayer groups are often segregated by gender

- groups like Promise Keepers are for men only

- father-and-son and mother-and-daughter events are segregated by gender

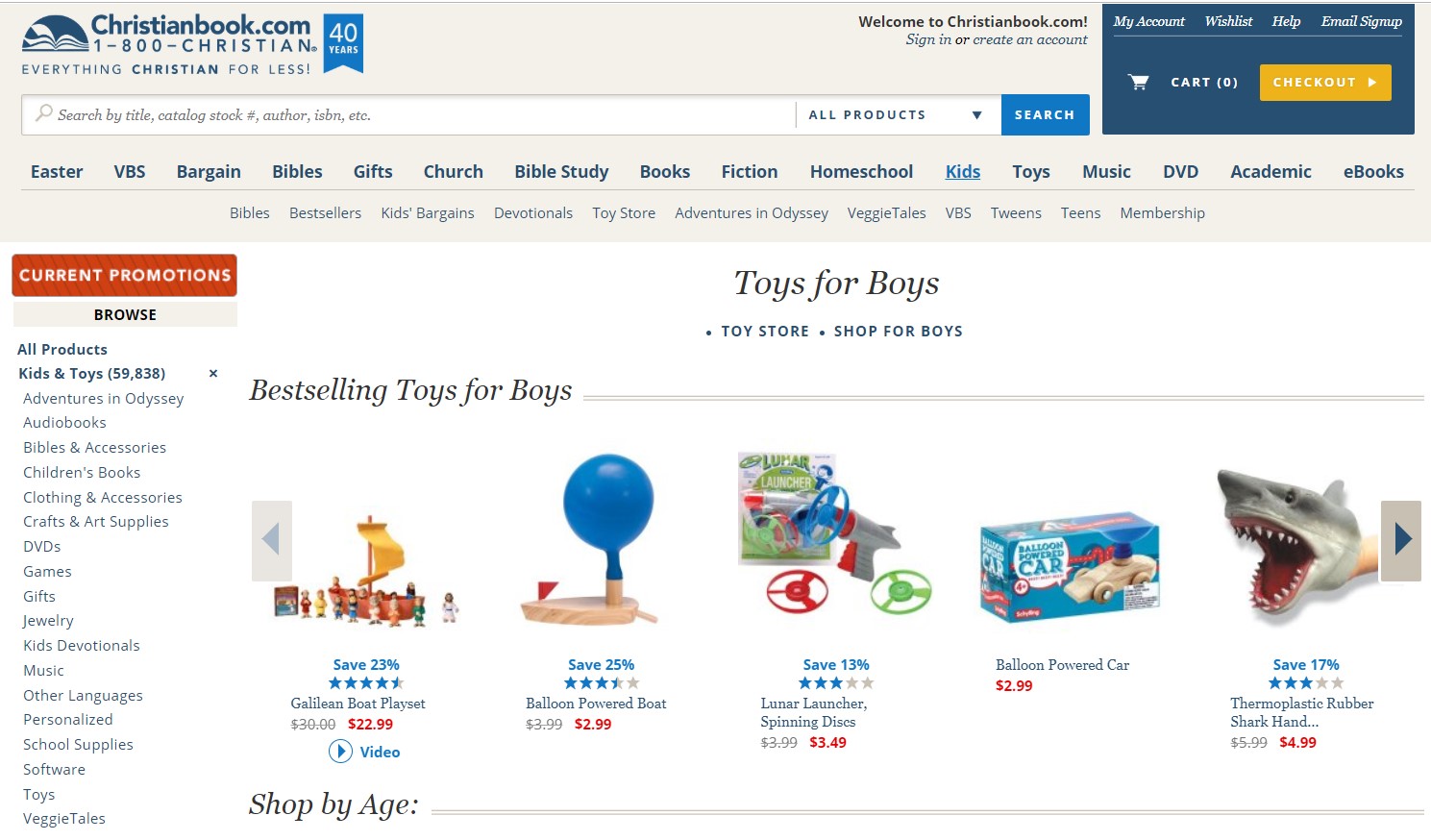

- kitsch sold at Christian bookstores is gendered more often than not, as are books, memorabilia, bibles, toys, and so forth

To illustrate that last point when teaching this chapter, I spend a considerable amount of time in class browsing Christianbook.com. Notably, almost every menu item (such as Bibles, Gifts, Books, Kids, etc.) has sub-categories divided between “for men” or “for women,” or, alternatively, “for boys” or “for girls.” Below are two screenshots that demonstrate a little of what we find.

I encourage readers to visit the site for themselves — it’s a treasure trove of data for gender-based analysis.

Ingersoll notes that although there are a wide variety of feminist evangelical voices in the evangelical subculture, they remain counter-hegemonic and have been unable to gain a hegemonic status. Why? Her explanation, in part, is that evangelical feminist cultural production has been primarily literary — i.e., through the production of feminist theology. As I note to my students, we’re surrounded by patriarchal culture almost all the time, but, for most Americans, we’re exposed to feminist culture rarely and intermittently. For my students, most of whom will go on to become therapists, doctors, lawyers, police officers, etc., their exposure to feminist literature in college might be their only exposure. The same is likely true for most American evangelicals.

Ingersoll writes,

Within the evangelical subculture, the opponents of hierarchical gender roles have largely abandoned the power of material culture to the proponents of gender ideology. … Evangelical feminists spend most of their time fighting institutional and theological battles, but dualistic constructions of gender are more readily represented materially than are fluid constructions that emphasize equality. … [T]he fact remains that gendered dualism is perpetuated on a popular level by virtue of the fact that the material culture that gives shape to everyday life reproduces it. (107)

One of the most compelling aspects of Ingersoll’s argument is that it addresses material culture without presenting it as a medium for the manifestation of “the Sacred.” On the contrary, on her account material culture is just one more weapon in the war over gender, useful for reproducing the status quo or challenging it. “Gender is evolving and malleable and at least partly explicitly produced and reproduced” (106), and material culture is one of the most important means of producing it.

In recognizing that material culture is not only representative of gender norms but also a way to produce such norms, we should take stock of how gender is being produced at our local Wal-Mart and Target as much as it is at Christian bookstores. As long as the aisles remain divided between all pink and all blue, red, and black, it’s no wonder that children grow up internalizing ideologies of gender difference rather than gender equality. The power of subtle arrangements indeed.