For a new Culture on the Edge series “You Are What You Read” we’re asking each member to answer a series of questions about books—either academic or non-academic—that have been important or influential on us.

3. Name one of your favorite books that’s not a theory book.

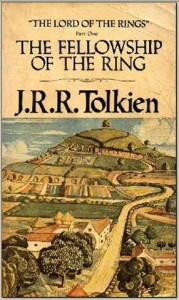

If I’m permitted to range further than my own scholarly expertise, it’s got to be any of those go-to works by Tolkien. My reason? I was a life guard at the local pool throughout high school and within a week or so of the end of grade 12 I broke both bones in my left leg, a little above the ankle, while on a diving board at the pool. (Yes, I was the diving instructor too—irony abounds.) We’d all take two bounces, to do anything in the air that struck us as interesting and who knows what happened to prompt that loud snapping noise that I hear a second before I felt it and flopped into the water. Up until that point in my life I’d not really read all that much; tackling 2001: A Space Odyssey in grade 7 or 8 was pretty rewarding (how cool was that monolith, right? And what about the last line concerning “a silent detonation that brought a brief, false dawn to half the sleeping globe”!), but, at least as memory serves, that was the only novel I’d so far read and enjoyed; all other reading was required for school and thus a task to get through. (Why did we have to read Four Feathers? And what was with all that dystopic stuff that one year—“beware of thy mutant” and soma vacations…?) Oh, and I also grew up in a gas station, owned and operated by my parents, with no other employees and my older siblings long out of the house. So it was a pretty hectic place, with people coming and going and the sometimes relentless “ding ding” of the bell going off every time a car drove in across the hose, announcing another customer. So into this context was introduced the immobility and slowed life that comes with a full leg cast for the entire summer of 1979. I don’t recall who recommended The Silmarillion to me but I read that one first, then moved on to the various Lord of the Rings volumes, and, in suitably backward order, ended with The Hobbit—those were the first books I ever read in that manner you hear people talking about, as if they had entered the story by becoming so engrossed in it, rushing to get back to it after dinner. I wasn’t a particular fan of scifi or fantasy, but for whatever reason, that summer I experienced reading in a whole new way. Now, I don’t want to be melodramatic, but I sometimes wonder what would have become of me, career-wise, had I not broken my leg on June 13, 1979, and had I not learned to—well, been forced to, really—take time to read. For, along with writing and talking, it eventually became one of the primary ways that I earn my livelihood today.

If I’m permitted to range further than my own scholarly expertise, it’s got to be any of those go-to works by Tolkien. My reason? I was a life guard at the local pool throughout high school and within a week or so of the end of grade 12 I broke both bones in my left leg, a little above the ankle, while on a diving board at the pool. (Yes, I was the diving instructor too—irony abounds.) We’d all take two bounces, to do anything in the air that struck us as interesting and who knows what happened to prompt that loud snapping noise that I hear a second before I felt it and flopped into the water. Up until that point in my life I’d not really read all that much; tackling 2001: A Space Odyssey in grade 7 or 8 was pretty rewarding (how cool was that monolith, right? And what about the last line concerning “a silent detonation that brought a brief, false dawn to half the sleeping globe”!), but, at least as memory serves, that was the only novel I’d so far read and enjoyed; all other reading was required for school and thus a task to get through. (Why did we have to read Four Feathers? And what was with all that dystopic stuff that one year—“beware of thy mutant” and soma vacations…?) Oh, and I also grew up in a gas station, owned and operated by my parents, with no other employees and my older siblings long out of the house. So it was a pretty hectic place, with people coming and going and the sometimes relentless “ding ding” of the bell going off every time a car drove in across the hose, announcing another customer. So into this context was introduced the immobility and slowed life that comes with a full leg cast for the entire summer of 1979. I don’t recall who recommended The Silmarillion to me but I read that one first, then moved on to the various Lord of the Rings volumes, and, in suitably backward order, ended with The Hobbit—those were the first books I ever read in that manner you hear people talking about, as if they had entered the story by becoming so engrossed in it, rushing to get back to it after dinner. I wasn’t a particular fan of scifi or fantasy, but for whatever reason, that summer I experienced reading in a whole new way. Now, I don’t want to be melodramatic, but I sometimes wonder what would have become of me, career-wise, had I not broken my leg on June 13, 1979, and had I not learned to—well, been forced to, really—take time to read. For, along with writing and talking, it eventually became one of the primary ways that I earn my livelihood today.

Naming two books is cheating I guess, but I adore Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. As Twain grew older — at least as I read him — he became almost as skeptical about morality as was Nietzsche. For Twain, humans are neither good nor evil; rather, human behavior simply follows from the processes socialization to which we’re subjected from the cradle, and moral evaluations of human behavior are not based on a universal ethics but are always relative to the sympathies with which one has been socialized. Consider the narrator’s commentary in Connecticut Yankee: Continue reading “You Are What You Read, with Craig Martin (Part 3)”

Naming two books is cheating I guess, but I adore Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. As Twain grew older — at least as I read him — he became almost as skeptical about morality as was Nietzsche. For Twain, humans are neither good nor evil; rather, human behavior simply follows from the processes socialization to which we’re subjected from the cradle, and moral evaluations of human behavior are not based on a universal ethics but are always relative to the sympathies with which one has been socialized. Consider the narrator’s commentary in Connecticut Yankee: Continue reading “You Are What You Read, with Craig Martin (Part 3)”

While I’m tempted to name one of my favorites by Althusser, Derrida, Foucault, Bourdieu, or Butler, I think I’ll go with Durkheim’s The Division of Labor in Society. While Elementary Forms seems to be everyone’s favorite in religious studies, I have a strong preference for Division of Labor. In Division of Labor we see the best and worst of Durkheim all at once: sometimes rigorous and sometimes sloppy in his argumentation, he delivers a devastating blow to methodological individualism, he shows how culture is fundamentally related to society or social structure, but — although he frequently departs from the self-serving views of his contemporaries — he speaks freely of “primitive savages” across the globe and ratifies a certain brand of European ethnocentrism. I love teaching Division of Labor because I get to show students a brilliant mind whose views deserve continual consideration yet not always acceptance. Every lecture turns out to be a love letter of sorts to Durkheim, but with a love that resists romaniticizing him and instead loves him despite his flaws.

While I’m tempted to name one of my favorites by Althusser, Derrida, Foucault, Bourdieu, or Butler, I think I’ll go with Durkheim’s The Division of Labor in Society. While Elementary Forms seems to be everyone’s favorite in religious studies, I have a strong preference for Division of Labor. In Division of Labor we see the best and worst of Durkheim all at once: sometimes rigorous and sometimes sloppy in his argumentation, he delivers a devastating blow to methodological individualism, he shows how culture is fundamentally related to society or social structure, but — although he frequently departs from the self-serving views of his contemporaries — he speaks freely of “primitive savages” across the globe and ratifies a certain brand of European ethnocentrism. I love teaching Division of Labor because I get to show students a brilliant mind whose views deserve continual consideration yet not always acceptance. Every lecture turns out to be a love letter of sorts to Durkheim, but with a love that resists romaniticizing him and instead loves him despite his flaws. During my senior year of college I picked up a copy of Stanley Fish’s The Trouble with Principle, and it has made an indelible impact on me. In the book, Fish suggests that abstract principles — specifically abstract liberal principles such as “freedom,” “equality,” “inclusion,” “tolerance,” or “neutrality” — are, in and of themselves, vacuous of any particular content and can, in practice, be turned to support just about any social agenda. To use another analytical vocabulary: abstract liberal principles are floating signifiers that, in context, can be fixed to any particular referent, depending on the skill of the rhetorician at work. Fish suggests that liberal proceduralism — the attempt to find and apply non-partisan political principles — is, ultimately, a theoretically bankrupt affair, as abstract principles only begin to take shape when fixed to partisan projects. If it’s politics all the way down, the presentation of one’s own view as above the fray can be reduced to a form of legitimation. That is not to say that what is theoretically bankrupt is not politically useful: in good Nietzschean fashion Fish assumes that partisan contestation is the nature of the game, and that presenting one’s partisan agenda as neutral is a powerful way of winning social and political contests.

During my senior year of college I picked up a copy of Stanley Fish’s The Trouble with Principle, and it has made an indelible impact on me. In the book, Fish suggests that abstract principles — specifically abstract liberal principles such as “freedom,” “equality,” “inclusion,” “tolerance,” or “neutrality” — are, in and of themselves, vacuous of any particular content and can, in practice, be turned to support just about any social agenda. To use another analytical vocabulary: abstract liberal principles are floating signifiers that, in context, can be fixed to any particular referent, depending on the skill of the rhetorician at work. Fish suggests that liberal proceduralism — the attempt to find and apply non-partisan political principles — is, ultimately, a theoretically bankrupt affair, as abstract principles only begin to take shape when fixed to partisan projects. If it’s politics all the way down, the presentation of one’s own view as above the fray can be reduced to a form of legitimation. That is not to say that what is theoretically bankrupt is not politically useful: in good Nietzschean fashion Fish assumes that partisan contestation is the nature of the game, and that presenting one’s partisan agenda as neutral is a powerful way of winning social and political contests. If I’m permitted to range further than my own scholarly expertise, it’s got to be any of those go-to works by Tolkien. My reason? I was a life guard at the local pool throughout high school and within a week or so of the end of grade 12 I broke both bones in my left leg, a little above the ankle, while on a diving board at the pool. (Yes, I was the diving instructor too—irony abounds.) We’d all take two bounces, to do anything in the air that struck us as interesting and who knows what happened to prompt that loud snapping noise that I hear a second before I felt it and flopped into the water. Up until that point in my life I’d not really read all that much; tackling 2001: A Space Odyssey in grade 7 or 8 was pretty rewarding (how cool was that monolith, right? And what about the last line concerning “a silent detonation that brought a brief, false dawn to half the sleeping globe”!), but, at least as memory serves, that was the only novel I’d so far read and enjoyed; all other reading was required for school and thus a task to get through. (Why did we have to read Four Feathers? And what was with all that dystopic stuff that one year—“beware of thy mutant” and soma vacations…?) Oh, and I also grew up in a gas station, owned and operated by my parents, with no other employees and my older siblings long out of the house. So it was a pretty hectic place, with people coming and going and the sometimes relentless “ding ding” of the bell going off every time a car drove in across the hose, announcing another customer. So into this context was introduced the immobility and slowed life that comes with a full leg cast for the entire summer of 1979. I don’t recall who recommended The Silmarillion to me but I read that one first, then moved on to the various Lord of the Rings volumes, and, in suitably backward order, ended with The Hobbit—those were the first books I ever read in that manner you hear people talking about, as if they had entered the story by becoming so engrossed in it, rushing to get back to it after dinner. I wasn’t a particular fan of scifi or fantasy, but for whatever reason, that summer I experienced reading in a whole new way. Now, I don’t want to be melodramatic, but I sometimes wonder what would have become of me, career-wise, had I not broken my leg on June 13, 1979, and had I not learned to—well, been forced to, really—take time to read. For, along with writing and talking, it eventually became one of the primary ways that I earn my livelihood today.

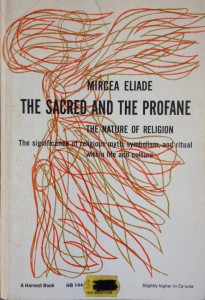

If I’m permitted to range further than my own scholarly expertise, it’s got to be any of those go-to works by Tolkien. My reason? I was a life guard at the local pool throughout high school and within a week or so of the end of grade 12 I broke both bones in my left leg, a little above the ankle, while on a diving board at the pool. (Yes, I was the diving instructor too—irony abounds.) We’d all take two bounces, to do anything in the air that struck us as interesting and who knows what happened to prompt that loud snapping noise that I hear a second before I felt it and flopped into the water. Up until that point in my life I’d not really read all that much; tackling 2001: A Space Odyssey in grade 7 or 8 was pretty rewarding (how cool was that monolith, right? And what about the last line concerning “a silent detonation that brought a brief, false dawn to half the sleeping globe”!), but, at least as memory serves, that was the only novel I’d so far read and enjoyed; all other reading was required for school and thus a task to get through. (Why did we have to read Four Feathers? And what was with all that dystopic stuff that one year—“beware of thy mutant” and soma vacations…?) Oh, and I also grew up in a gas station, owned and operated by my parents, with no other employees and my older siblings long out of the house. So it was a pretty hectic place, with people coming and going and the sometimes relentless “ding ding” of the bell going off every time a car drove in across the hose, announcing another customer. So into this context was introduced the immobility and slowed life that comes with a full leg cast for the entire summer of 1979. I don’t recall who recommended The Silmarillion to me but I read that one first, then moved on to the various Lord of the Rings volumes, and, in suitably backward order, ended with The Hobbit—those were the first books I ever read in that manner you hear people talking about, as if they had entered the story by becoming so engrossed in it, rushing to get back to it after dinner. I wasn’t a particular fan of scifi or fantasy, but for whatever reason, that summer I experienced reading in a whole new way. Now, I don’t want to be melodramatic, but I sometimes wonder what would have become of me, career-wise, had I not broken my leg on June 13, 1979, and had I not learned to—well, been forced to, really—take time to read. For, along with writing and talking, it eventually became one of the primary ways that I earn my livelihood today. With my earlier career in mind, it would have to be Terry Eagleton’s Literary Theory: An Introduction (1983), though I have the 1989 edition, which I bought in Toronto in January of 1991 (evident, again, from my dated front inscription). It too was a book recommended to me by Neil McMullin, and it makes sense to be dated a little later than my copy of The Sacred and the Profane, for (at least as I remember it now), I wasn’t dipping into theory until I’d confirmed that there was a project of some sort to be done on the widespread essentialist understanding of religion as socio-politically and historically autonomous. So having decided there was indeed a project here, at least as applied to Eliade’s one book, the challenge was to start reading as much of his work as I could, and to then be able to make the case that his work exemplified (though it didn’t necessary cause) much wider trends evident throughout the field, and then to come up with a set of tools to critique this approach and identify its practical implications. And that’s where Eagleton’s work came in—helping me to make the shift from seeing words and texts as inherently meaningful, as being in reference to objects in the world that we were talking about, to identifying the apparatuses necessary to signify these scribbles that we call letters, to read them as meaningful—to, as I might now say, operationalize them. Given that I was a sciences undergrad, I’d only taken the virtually mandatory first year English Lit course, with my thick two volume Norton anthology, so reading literary theory, much less the social theory I later came to read, was completely alien to me.

With my earlier career in mind, it would have to be Terry Eagleton’s Literary Theory: An Introduction (1983), though I have the 1989 edition, which I bought in Toronto in January of 1991 (evident, again, from my dated front inscription). It too was a book recommended to me by Neil McMullin, and it makes sense to be dated a little later than my copy of The Sacred and the Profane, for (at least as I remember it now), I wasn’t dipping into theory until I’d confirmed that there was a project of some sort to be done on the widespread essentialist understanding of religion as socio-politically and historically autonomous. So having decided there was indeed a project here, at least as applied to Eliade’s one book, the challenge was to start reading as much of his work as I could, and to then be able to make the case that his work exemplified (though it didn’t necessary cause) much wider trends evident throughout the field, and then to come up with a set of tools to critique this approach and identify its practical implications. And that’s where Eagleton’s work came in—helping me to make the shift from seeing words and texts as inherently meaningful, as being in reference to objects in the world that we were talking about, to identifying the apparatuses necessary to signify these scribbles that we call letters, to read them as meaningful—to, as I might now say, operationalize them. Given that I was a sciences undergrad, I’d only taken the virtually mandatory first year English Lit course, with my thick two volume Norton anthology, so reading literary theory, much less the social theory I later came to read, was completely alien to me.  as

as