By Andie Alexander

I’m currently creating an index for an edited volume, and while I’ve repaginated an index before (for the new edition of a book), this is the first time that I have ever compiled an index from scratch. As I’ve been going through the book, I’ve been marking all of the important thoughts, people, theories, etc. Well, I say “important” not because those ideas and names are self-evidently interesting; after all, who would think that Ebenezer Scrooge or the recent Disney⋅Pixar film Inside Out would be among the indexed items for an edited volume in religious studies?

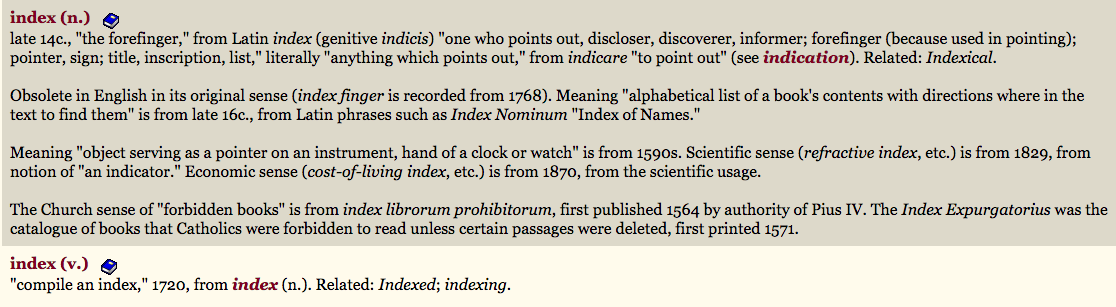

Much like the above etymological definition of “index” suggests, indices (or rather indexers — i.e., me), to be more precise, do “discover,” “point out,” and “disclose” information to their readers. That is to say that indices are neither self-evident nor neutral descriptors of a book’s contents. For what would a neutral descriptor even be? The number of times a word appeared? Well no, because apart from the word “the” making an extraordinary number of appearances, even doing such a word count seems to privilege quantity of word usage over the general argument those words are making. That said, indices are anything but neutral and are themselves, by nature of being a human production, very much situated and, yes, biased (they have a viewpoint). So for me, the indexer, to compile a list of what I and those editing the volume deem relevant for the work, I must have a certain understanding of the argument of the book to determine whether Ebenezer Scrooge is worth including in the index — worth offering to a reader as a hint of more to come. That is, in selecting people, places, and ideas for the index, I have to consider which ones I think best direct and support the arguments, theories, and e.g.s of the volume.

The choices involved in indexing remind me of the time I put together my first would-be syllabus for an Introduction to Religious Studies course as a class assignment. In fact, the assignment prompted a debate among the class of how best to put such a document together. Given that our course was a seminar on Religions in America, the question of what to include in American religious history syllabus (i.e., Church history, Southern history, Indigenous history, African American history, etc.) became our primary focus. Should we attempt to make a syllabus that attempts to be all-inclusive or should we instead acknowledge our own biases and perspectives in the process? Having chosen the latter, I was chastised by some of my classmates for having an intro to religious studies syllabus that addressed more social theory than it did “religion”. My response was that all-inclusive narratives of religious history in the U.S. aren’t necessarily unproductive, but that in my mind, that they distract us from seeing different agendas at work.

By constructing a syllabus rooted in different theories of religion, I was not only acknowledging my perspectives but also constructing a particular argument about the academic study of religion. As one of my professors once said (influenced by J. Z. Smith, as I recall), the syllabus was the first reading assignment of the semester because it gave the students an opportunity to learn about them (the prof) and their approach — the class itself was an argument. That has always stuck with me throughout my studies, reminding me to read everything with a critical eye: primary sources and secondary sources alike.

Whether it’s a primary source on religious ritual, a secondary analysis of the Gospels, a syllabus, or even an index — these are all products of human study and analysis, however neutral they may appear or claim to be. With that in mind I began to approach my indexing task not as a descriptive list, but more as a a bulleted argument for the volume itself. While I try to catalog the terms I think would be most useful to a reader, I do so in such a way to support the overall point of the book. For while I could choose anything from the text to include in the index, unless Ebenezer Scrooge and Inside Out work as useful e.g.s for its authors’s larger argument, then including them ceases to appear descriptive and instead seems misguided. The supposed descriptiveness of an index (or syllabus, etc.) only works inasmuch as the same ideas are echoed throughout.

So the next time you flip back to the index to search for a term or idea, pay attention to the ways in which it’s constructed, i.e., what someone is trying to “point out.” For those terms were carefully chosen over others (if it’s a good index, that is) to help focus and delineate the argument of the book — it’s anything but descriptive.

.

Andie Alexander is an M.A. student at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her research focuses on identity construction, discourses on classification and boundary construction, the practicality of definition, and public/private discourses with regard to issues of social group formation and nationalism in the U.S. She also contributes to the Studying Religion in Culture Grad blog. Read her posts here. Andie is also the Online Curator here at Culture on the Edge.