by Martie Smith

The vision of white racial purity that drove the Nazi regime to perpetrate genocide in the mid-twentieth century has persisted into the present, most recently made visible by American white supremacist groups. The idea that bodies not only represented but also manifested an essential cultural supremacy may seem to be an outdated and backward view of the world. And yet, a recent surge in popular interest in ancestry and DNA may reveal the ways in which biological essentialism continues to inform popular American notions of identity.

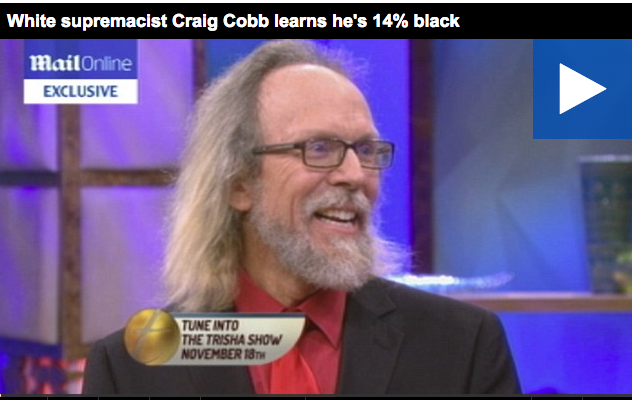

In the wake of the 2017 KKK rally in Charlottesville, VA, articles and exposés on the alt-right, KKK, white supremacy, and neo-Nazi movements in America are flooding newsfeeds everywhere. Two of those recent articles connect white nationalist movements with ancestry and DNA testing, raising questions about our general assumptions on relationship between biology and identity. Headlines, such as Sarah Zhang’s article in The Atlantic, “When White Nationalists Get DNA Tests That Reveal African Ancestry,” and Tom Hale’s post on IFL Science, “White Supremacists Taking Ancestry Tests Aren’t Happy About The Results” play on the generally assumed biological basis of identity. (Similar articles can be found here, here, and here.)

(If the video player doesn’t work, click here.)

These headlines work on multiple levels, but mainly by assuming that the reader will automatically guess the irony of white supremacists having non-white ancestry. This notion itself reveals a lot about our own categories of identity—if white supremacists discovering they are not “really” white is the point of these exercises, we are assuming that ancestry tests will confound white supremacist’s own categories of biological essentialism (remember those “blood and soil” chanters in Virginia?). However, a closer reading of these articles reveals the ways in which even the most staunch believers in biological descent as the foundation of identity can easily transform meaning when those categories are challenged. At the same time, opponents of white supremacists also maintain certain assumptions about biological ancestry and identity.

Many of these articles cite the recent research by sociologists Aaron Panofsky and Joan Donovan, who studied the ways in which members of Stormfront (a white supremacist forum) responded to genetic ancestry tests (GATs). You can read a preprint of the article here. What they found was an overwhelming tendency of white supremacists to interpret the tests in ways that simply reimagine and reconstitute white identity. That is, even if their ancestry did not reveal a genetic “purity,” they remained confident in their purity by simply reinterpreting their results to fit their existing categories. As Panofsky and Donovan note, “Despite their essentialist views of race, much less than using the information to police individuals’ membership, posters expend considerable energy to repair identities by rejecting or reinterpreting GAT results.” But should we be surprised by these findings? Perhaps, but only if we expect genetic ancestry tests to have some connection to biological identity outside of interpretive categories. This leads to a bigger question: When do we deploy the rhetoric of biological essentialism? And to what ends?

Maybe you have seen ancestry test commercials that feature individuals whose results make them challenge who they are a deeper level. (See Russell McCutcheon’s post from last summer on this topic and watch these recent commercials about Kim and Livie’s results.) In these instances, ancestry is advertised as a way to connect to others through the recognition of one’s own genetic profile, which is never as clear-cut as the participants assume. The DNA Discussion Project is one example of a university program that encourages their community to “talk about diversity in a new, positive and engaging way” by providing “ancestry DNA tests to hundreds of students, faculty, and staff at the University” in order “to help them find out who they really are.” While this may work for those who are looking to reinforce multicultural identities or find new facets of “who they really are,” it also points to the ways in which race and ethnicity remain tied to biology even for those who want to use these categories to undermine racism. In fact, we should note that these more progressive ends can also go awry. A good example of the appropriation made possible by ancestry tests can be found in stories (like this one) about the “uncovering” of Native American identity. In these cases genetic testing allows white Americans to claim indigenous identity even if they have no lived experience with indigenous communities.

Again, should we be surprised that GATs can be deployed to achieve so many different ends? Ancestry tests may seem to have two simple interpretive outcomes: in the most generous reading, they allow individuals to connect to identities previously seen as foreign or other, in the worst case scenario they contribute to ideologies of racial purity like those at work in the Nazi final solution. However, both of these interpretations rely on biological essentialism to inform identity construction. In this light, genetic ancestry tests reveal much more about our social constructions of reality than they do about any “really real” identity waiting to be uncovered. In fact, it is around the new and unpredictable interpretive possibilities of genetic research that many scholars have very real concerns about the future of biological essentialism and American racism. Sarah Zhang sums this up well in her Atlantic article, quoted below. And while white supremacists’ interpretations of genetic testing are overtly racist, the widespread use of ancestry tests by ordinary people looking to find authenticity in their genetic codes reminds us that biological essentialism remains a powerful marker of identity for many Americans.

.

Martie Smith is an Assistant Professor of Religion at Denison University in Granville, Ohio. Her current research and teaching interests include North American religious pluralism. Her courses focus on the diversity of the American religious landscape, especially the ways in which race, gender, and ethnicity are connected to religious identities and the significance of material culture and lived religious experience in American life. She serves on the Board of Directors for the Institute for Diversity and Civic Life, a non-profit educational organization based in Austin, Texas, and sits on the Executive Committee for the North American Association for the Study of Religion. Read Martie’s posts here.