10. Understanding the system of ideology that operates in one’s own society is made difficult by two factors: (i) one’s consciousness is itself a product of that system, and (ii) the system’s very success renders its operations invisible, since one is so consistently immersed in and bombarded by its products that one comes to mistake them (and the apparatus through which they are produced and disseminated) for nothing other than “nature.” – Bruce Lincoln, “Theses on Method“

The recent claim by Zimerman trial juror B37 in an exclusive interview with Anderson Cooper that, “[Zimmerman’s] heart was in the right place. It just went terribly wrong” has come under fierce attack by many who believe Zimmerman is guilty for pursuing and murdering Trayvon Martin. I, myself, was delighted to see a public conversation unfold about this juror’s curious, even callous statement. Many are angry that such niceties (i.e., interpretive generosities) were extended to Zimmerman in a way that wasn’t to Martin – but interestingly, few if any, questioned the appropriateness of such a personalized qualifier in relation to the presumption of innocence. B37’s claim of empathy (for and on behalf of Zimmerman) relies upon some privileged and unique access to the interiorized comportment of Zimmerman’s un/consciousness, a methodological problem with palpable social consequences.

B37 doesn’t know Zimmerman in a “personal” capacity—which really wouldn’t matter one way or another. To think otherwise would be to assume that social actors are always and fully conscious of why we do what we do, let alone why others do as they do—but she also seemingly expects her moralistic, value-laden claim to be heard as some cross-cultural universal truth of ‘goodness’ and ‘virtue’ that the public can then identify with. To “authentically” back this up, she adds to her statement that she’d personally feel comfortable with someone like Zimmerman living in her neighborhood. Therefore, she seems to be concluding, the public should be just as comfortable with someone like him walking freely in society as well. After all, he just wants to do well and protect his neighborhood and the world against crime and wrongdoing with his “heart in the right place” and all.

There was something noble she saw about an armed man wanting to “protect” his neighborhood from delinquency, to the point of putting himself in harms way or being willing to kill for what he believes in. For B37, Zimmerman’s good intentions, “…just got displaced by the vandalism in the neighborhoods, and wanting to catch these people so badly that he went above and beyond what he really should have done.” I wonder if she would offer the same reading of others who resort to deadly violence in the protection of the territories they claim, say, to Palestinian suicide bombers?

This juror’s mystical claims are probably not quite the type of behavior that we expect to pass as “verifiable facts” in the “court of law”—we can presume that her post-trial sentiments of empathy were probably also evident while deliberating among other jurors during the trial. They are, to use Lincoln’s words, “invisible operations” that go largely unquestioned (in a variety of spaces) more often than we’d like to think. It is not my goal here to conflate academic apriorism with perceptions of Martin’s murder, but rather, to indicate that B37’s claims involve a methodological confusion that often obscures ideology for nature, public for private and beliefs for intentions.

For example, we often come across such correlations in the study of religion or surveys about religion in public life that proffer its objects of study as inner essences, intentions, intuition, consciousness, and “natures,” all of which need to be interpreted by the generous hermeneut. Along these lines, the study of religion is often associated with, and assumed to represent, all things affirmative, moral, right, and just. Much like the presumed foundations of the legal system, which holds ‘intentions’ and ‘motivations’ in such high regard.

The problem with such thinking is that it arrests the category of religion to something that is inward (personal and private) rather than outward (public and observable) thereby protecting whatever it is from external scrutiny and rendering it something that is therefore incontestable. This type of reasoning assumes there is a “thing” called religion (rather than processes that come to be understood as religion) and this “thing” — sometimes called x, y, and z — can be intuitively analyzed from the inside à out and assumed to be examined from the outside à in. Prioritizing the inside (e.g., B37) assumes these constructs to be ahistorical, natural and lodged within the consciousness of the social actor a priori while the position that prioritizes the outside (e.g., that of Lincoln) emphasizes historicity and the public social process by which we come to believe such things to be real.

This suggests, perhaps, that someone like juror B37 might have had little use for other data or proof, as the only pertinent evidence (it seems from her own post-verdict admission) might have been her inner feelings about both Zimmerman and Martin (“truthiness” as Stephen Colbert once called it, that feeling in your gut…). In other words, as Russell McCutcheon has suggested about the academic study of religion, many, like B37 are walking around:

“Believing religion, [“good intentions,” “heart of hearts”] somehow to provide privileged access to some posited transcendent realm of meaning, they search for their hermeneutic philosopher’s stones and fail to understand feelings such as fear or awe as ‘taught’ and therefore products of social life.”

…and I would add, they fail to understand their own culpability in perpetuating and hiding behind an ideological construct that not only gets Zimmerman off the hook, but justifies the injustice through appeals to some privileged data.

McCutcheon’s argument nicely sums up what is methodologically at stake here, whether it be the feel-good claims by juror B37 (whether one agrees with her or not) or what often passes as verifiable data in the academic study of religion or even in the courtroom. Because many of us see Zimmerman’s actions as vile it’s easy to feel that the math of B37’s sentiments doesn’t add up. But under different circumstances perhaps, such opinions would probably pass as ordinary and therefore go unquestioned.

Rather than taking a supernatural approach, had B37 (and others) taken a more critical one, she would have interrogated her own fuzzy-wuzzy-feel-good claims and perhaps come to see that Zimmerman’s fear of Trayvon, a fear of death to the point of killing another, wasn’t an innocuous protectionist feeling emerging from his heart of hearts, but rather, a social product – ideology – something he was taught to do and shaped by outside forces.

Far too often, we make private (a good heart) what is in reality, social and public (the socialization of what ‘good’ constitutes) for our own means, ends, and interests (in this case, B37’s justification of a ‘Not Guilty’ verdict). If only B37 had used more “head” than “heart” she, and others, might have come to see that Zimmerman’s motivations and intentions are not privatized as she assumes; rather, they are ideological products of the social world and should be treated/tried as such. The continued use of her cheery and constructed inner Zimmermanness as evidence for his innocence at best makes a mockery of what evidence gets counted as “evidence.”

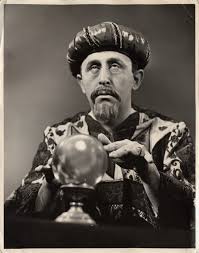

Simply put, crystal balls should not replace critical inquiry.

Another juror is now talking….

“It’s hard for me to sleep, it’s hard for me to eat because I feel I was forcefully included in Trayvon Martin’s death. And as I carry him on my back, I’m hurting as much Trayvon’s Martin’s mother because there’s no way that any mother should feel that pain,”

“George Zimmerman got away with murder, but you can’t get away from God.”

http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/juror-b29-maddy-says-zimmerman-got-away-with-murder/2013/07/25/a636ec2a-f55a-11e2-aa2e-4088616498b4_story.html