Our campus has a new painting, hanging in the lobby of our main library, depicting the University of Alabama prior to the Civil War — near the end of which most of the campus was burned down by northern troops passing through the city. But here, in this roughly 6 by 14 foot vibrant painting, we see the Rotunda brought back to life, as well as several other now missing buildings (only the remains exist today, such as a pile of debris that was once Franklin Hall that has come to be known as “the Mound“).

I walked over to see it the other day and met a grad of our program who, while also looking at it, remarked that the painting had no soul — now, I don’t know what exactly soul refers to, of course, but he couldn’t figure out what the point of the painting was (apart from documenting historic architecture, I guess) or why many in it were waving at each other.

By my count, there are 29 people in that picture (24 of whom are men), and 9 of them are greeting each other (either waving or hat-tipping). So while the careful reconstruction of the long lost buildings has received much of the press around its unveiling, it’s these people and their mutual acknowledgments that most attract my attention.

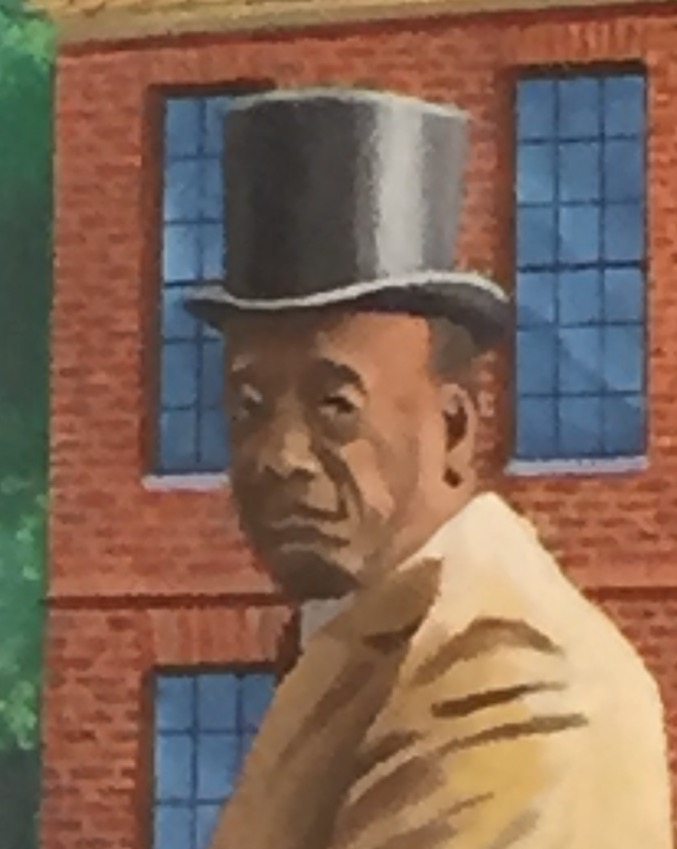

Correction, not all of these people but one in particular, the man at the far left, the one driving the cart, over on the other side of that tree. The one not waving at anyone but, instead, the one who seems to be staring straight at me.

Given what’s happening on a variety of US campuses right now (Missouri and Yale to name but two), let alone the complex history of race on our own campus — not to mention across the South or even the country as a whole — it’s tough not to walk up to that painting and see the color of people’s skin as being significant; I see three people of African descent in that picture, and, unlike the whites (some of whom, I think it fair to say, are just lounging), they’re all working: one man holds a horse, another unloads a trunk from a wagon, and the third, pictured above, drives a carriage. But it’s not just work, of course; for, given the history of the South, it’s not much of a leap to read them all as being slaves — as people, owned by yet other people, whose labor was essential but largely unseen.

But this one man is the only person in the foreground whose face we clearly see.

So while some might accuse me of a naive or overly generous reading of this painting, I see that one man, the one who seems to be looking me squarely in the eyes, as rather significant. For although he’s on the margin (literally but also socially, of course), he’s anything but invisible. And while his face strikes me as affectless and flat as the painting itself, he holds my gaze nonetheless.

Why?

Because I know that he sees me.

And I therefore know that he sees me seeing him.

His presence is therefore apparent to the viewer, is noted, and, though historic, is something that I, in the here-and-now, have got to come to terms with. For, unlike others in that painting, who merely greet one another, as our gaze meets it is this man, at the painting’s edge, who greets the viewer.

In his own compartment, to the left of that framing tree that cuts his wagon in half, a tree that could have easily defined the limits of the scene, he is the only character who is preoccupied not with acknowledging the others who are stuck in that two dimensional painting (those who would more than likely not have acknowledged him, back in the day) and thus the only one not reinforcing the picture’s self-referential nature; instead, he breaks the fourth wall, looking out into the abyss of third dimension, gazing back at us. So while I’m not sure what the artist did or did not intend — Why is he there? Was he an after thought? How does one include race in a painting such as this? — I see this man as possibly inviting (or should I say demanding? Maybe daring?) us to see him, to take account of him, of his time and his situation, of the fact that, though driving off the scene’s edge, the labor of the people he represents constitutes the center of that picture by making it all possible to begin with. (After all, they say that slave-made bricks were recovered from the ruined campus and used to create the first building on our reconstructed era, don’t they?)

Now, while I don’t wish to pretend that this reading makes the painting revolutionary or progressive, I also don’t wish to dismiss the picture as a PR coup that quite literally paints a far too rosy picture of what many would see as our institution’s less than stellar past. Instead, standing in the lobby of Gorgas Library, talking to a grad of our Department, it reminds me not only of the complexity and even contradictory nature of any text, not to mention the limits of intention in explaining any artifact, but also the fact that meaning-making requires a (usually unacknowledged) collaboration between author and reader, between the viewer and that which is seen.

And I can’t help but see that man. Perhaps because he’s the only one who greets me.

So does the painting have a soul? I’m not sure; but if it does it might be in what you decide to do with the fact that you too might see this man watching you as you watch him — i.e., what you do with this knowledge that one can’t just look right through others?