While listening to the radio on the way home from work the other day I caught an interview with Rachel Renee Russell, author of the bestselling series of adolescent novels, The Dork Diaries — the fictional diaries of a 14 year old girl. What caught my ear was the point at which the interviewer brought up the fact that she is African American while her teenage protagonist is not. Russell replied:

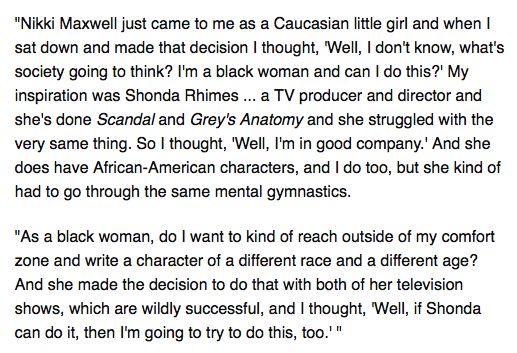

While listening to the radio on the way home from work the other day I caught an interview with Rachel Renee Russell, author of the bestselling series of adolescent novels, The Dork Diaries — the fictional diaries of a 14 year old girl. What caught my ear was the point at which the interviewer brought up the fact that she is African American while her teenage protagonist is not. Russell replied:

So here’s my question: when is choice merely personal and when is it political? Or better put, how do we decide when to classify it as one or the other? For we all know the consequences that sometimes attend what is commonly termed the appropriation of other people’s voices — but the key, I think, is that word “sometimes”; for, judging from this interview, there are times when it is apparently just a challenging mental exercise, a creative reach outside your comfort zone — in a word, merely a personal choice. At least this is how novelists and anthropologists in dominant groups once rationalized speaking in other people’s voices — until they were called on it, that is.

So here’s my question: when is choice merely personal and when is it political? Or better put, how do we decide when to classify it as one or the other? For we all know the consequences that sometimes attend what is commonly termed the appropriation of other people’s voices — but the key, I think, is that word “sometimes”; for, judging from this interview, there are times when it is apparently just a challenging mental exercise, a creative reach outside your comfort zone — in a word, merely a personal choice. At least this is how novelists and anthropologists in dominant groups once rationalized speaking in other people’s voices — until they were called on it, that is.

So the question is whether there are political consequences regardless who makes the choice to speak in the voice of an other? Feminist theorists have taught us this, no? Unfortunately, it’s not something the interviewer followed-up on in this case. But might we? In fact, could we even press it far enough to question just what’s so authentic in the so-called others’ voices that only they can speak them? (After all, not all 14 year old white girls are members of the same, say, economic class or regional group, so we’d be in error to think that they all spoke with the same voice, echoing the same concerns and thus sharing the same identity, no?) What’s more, is writing — whether scholarly or fiction — best understood as an act of faithful reproduction (in which case Russell is to be critiqued if she doesn’t “get it right” [judged how, I’m not sure]) or inventive creation driven by the interests and goals of the writer and her imagined audience (in which case Russell, like anyone else, is free to imaginatively invent)?

Simply put, how do we decide who gets to speak, and as whom?