History is a funny thing — we think it’s removed from us and somewhere in the past, yeah, but inasmuch as we know about it, it’s in the present, right in front of our eyes. In fact, if it isn’t in the present — some tattered artifact settled into our context and far removed from whatever setting it might have once been in — then it might as well be that proverbial tree falling in a forest with no one aware of the crash.

History is a funny thing — we think it’s removed from us and somewhere in the past, yeah, but inasmuch as we know about it, it’s in the present, right in front of our eyes. In fact, if it isn’t in the present — some tattered artifact settled into our context and far removed from whatever setting it might have once been in — then it might as well be that proverbial tree falling in a forest with no one aware of the crash.

For that tree, there, exists here only in the imaginations of the people telling the story.

In the present.

As do the original contexts of any historical artifact. They’re mere figments of our imaginations. Like Toronto back in 1971.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

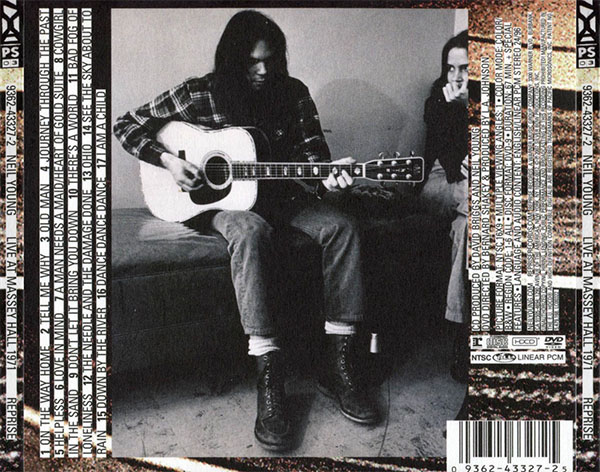

A few years ago I bought a CD that I’ve sometimes used to make students aware of just how complicated this thing called history — or better, history writing — is. It’s a recording of a Neil Young concert in, you guessed it, Toronto in 1971, that, until 2007, hadn’t been released.

Give it a listen:

Did you catch the start — just after he spanks some in the audience for distracting him by taking photos — when he said: “This is a new song…, that I wrote about my ranch…..” This is the intro to a song that was first released the following year, on his 1972 album “Harvest.”

Anyone who knows Neil Young knows “Old Man.”

Old man, take a look at my life. I’m a lot like you were….

The generation gap being what it is, I know that some students who now hear the song don’t know it but for those forced to listen to their parents’ music the opening few chords — once he starts into the song — immediately broadcast what’s coming.

But the really interesting thing to me is that it’s fair to assume that pretty much no one in that audience had ever heard that song before — it was, after all, “a new song,” not even released on vinyl yet and certainly not on the radio. So we have here a fascinating little moment of time traveling — we, in the present, are listening to the familiar by eavesdropping on a moment when people in the past were confronted with the unfamiliar. And my bet is that, because we can’t unhear the song that we already know so well, we can never conjure up the innocence of the audience that day — an experience lost to time that we can only imagine because of an artifact that we possess here and now, that we call an audio recording.

But the really interesting thing to me is that it’s fair to assume that pretty much no one in that audience had ever heard that song before — it was, after all, “a new song,” not even released on vinyl yet and certainly not on the radio. So we have here a fascinating little moment of time traveling — we, in the present, are listening to the familiar by eavesdropping on a moment when people in the past were confronted with the unfamiliar. And my bet is that, because we can’t unhear the song that we already know so well, we can never conjure up the innocence of the audience that day — an experience lost to time that we can only imagine because of an artifact that we possess here and now, that we call an audio recording.

He wasn’t talking to us, when he introduced the song, for we weren’t there and, besides, we already know all the words. So we can’t even imagine that moment when it was new.

It’s past.

It’s gone.

We’re privileged.

I’m not a lot like you were.