“World religions” as a way of organizing the world have become the focus of scholarly critiques (including my recent post) that connect this discourse to the interests and assumptions of European Christians. In the midst of such critiques, some minority/marginalized groups also have adopted the concept of world religions because it can be useful to them. As a case in point, Rajan Zed,who self-identifies as a “Hindu statesman” and the president of the Universal Society of Hinduism, issued a press release earlier this week over the release of information on the cheating website Ashley Madison and subsequent headlines that 1 in 5 in Ottawa are enrolled. Continue reading “Using World Religions”

“World religions” as a way of organizing the world have become the focus of scholarly critiques (including my recent post) that connect this discourse to the interests and assumptions of European Christians. In the midst of such critiques, some minority/marginalized groups also have adopted the concept of world religions because it can be useful to them. As a case in point, Rajan Zed,who self-identifies as a “Hindu statesman” and the president of the Universal Society of Hinduism, issued a press release earlier this week over the release of information on the cheating website Ashley Madison and subsequent headlines that 1 in 5 in Ottawa are enrolled. Continue reading “Using World Religions”

Is the Decline in Christianity Overstated by the Pew Survey?

Steven Ramey’s post originally appeared on the Huffington Post Friday and is republished here.

“Christians Decline Sharply as Share of Population” is a big headline of the Pew “America’s Changing Religious Landscape” report published this week, but the data in the survey tells us more about changing ways that people respond to surveyors. Therefore, the consternation and celebration of commentators may be overstated. Both the Washington Post, which emphasized that decline of Christianity and the growth of “secular” attitudes, and the Times of India, which celebrated the increase in Hindus as Christians declined in the U.S., may be overstating the significance of the results. In contrast, the Atlantic argued against the narrative of rising secularism, asserting that the U.S. is still a predominately Christian nation and still religious, with over 70 percent of the population identifying as Christian and 44 percent of those who identified as unaffiliated asserting that religion is very or somewhat important to them. These differing assertions miss the strategic nature of identifications and the limits on what a survey can measure.

The Atlantic article emphasized the increasing number of individuals leaving the religions in which they were raised, suggesting that people are “choosing their own beliefs.” While the language of choice and freedom fits with the U.S. national identification as a land of freedom, people are not simply free to choose any religious identification that they want. The IRS and federal courts still determine what counts as a religion and thus receives tax benefits and legal protections/limitations. Efforts to claim that a strip club is a church to circumvent the rejection of their permit application and that smoking marijuana is a religious practice have been met often with skepticism. On a personal level, many perceive pressure from family and peers that can influence how they identify.

The limitations on choice are also apparent in the survey itself. The initial Pew question specifies general groups, “Are you Protestant, Roman Catholic, Mormon,

Orthodox such as Greek or Russian Orthodox, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, atheist, agnostic, something else, or nothing in particular?” Overall, less than two percent of those surveyed responded with “something else.” When few vary outside of those eight broad groups and three unaffiliated categories, the limited nature of choice is apparent. Within the confines of the survey, respondents also are limited to one religion, even though some in the United States and other parts of the world identify with two or more religions, such as an Episcopalian who also identifies as Zen Buddhist. Moreover, when responses were not specific enough, such as a specific denomination for Protestants, surveyors assigned those vague denominational responses to set Protestant categories “based on their race and/or their response to a question that asked whether they would describe themselves as a ‘born-again or evangelical Christian.'” Survey respondents had to fit into the specific methodology of the survey itself and the assumptions behind it.

From the IRS to those who produce surveys, these constraints on religious identifications are typical of any identification. You can identify however you want, but if others (family, peers, employer, government) do not recognize that identification, your assertion (like a vague survey response) is not very productive. All of this highlights how any identification, including religious affiliation, is strategic, as people respond according to how they want others to perceive them and what identification best produces that perception. The strategic nature of any identification provides a different, partial explanation for the Pew survey results. The changes over time in the numbers claiming a religious affiliation should be seen as, first and foremost, a change in perception of what affiliation is socially acceptable and useful. Such a change, then, may be less about shifts in practice and belief than social perception and pressure. (Self-reports about practice or belief are also strategic and may not capture significant change in thought or practice.) Despite the media articles that the Pew report generates, the data tells us very little beyond changes in how people are willing to present themselves to anonymous surveyors. That change is itself an interesting development, but its implications are much more difficult to define than a simple reference to growth or decline of differing groups.

Photo credit: Boarded up church in Warm Springs by McD22 via Flickr (CC-BY-2.0)

Residual Assumptions

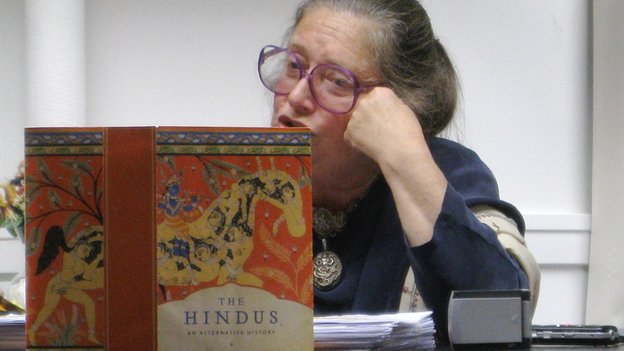

In a recent email discussion among scholars about general issues of representations and Wendy Doniger’s controversial book (about which I have written on Culture on the Edge and Bulletin for the Study of Religion blog), P. Pratap Kumar, a colleague in South Africa, framed the issue through a clear, though contrived, contrast between the scholar and the devotee. He wrote,

Someone who is raised as a Hindu grows up listening to religious songs at Satsangs and even through Bollywood religious songs (there are plenty of Bollywood religious songs that Hindus listen to with utmost devotion) and never would have known that their Hindu texts contain many erotic statements and not just the singular term Linga. But on the other hand, scholars especially from the outside Hindu tradition (be they western or eastern) begin with Sanskrit language and then reading the highly specialised texts where they find statements that devout Hindus would have never heard of. From scholar’s reading, there are indeed very detailed erotic references in many Hindu texts, . . .

We as scholars have to talk about these things because these matters are there in the texts from the Rig Veda to the epics in plenty of places. It is hard to fault a western scholar or any non-Hindu scholar for pointing these out and translating them for what they are.

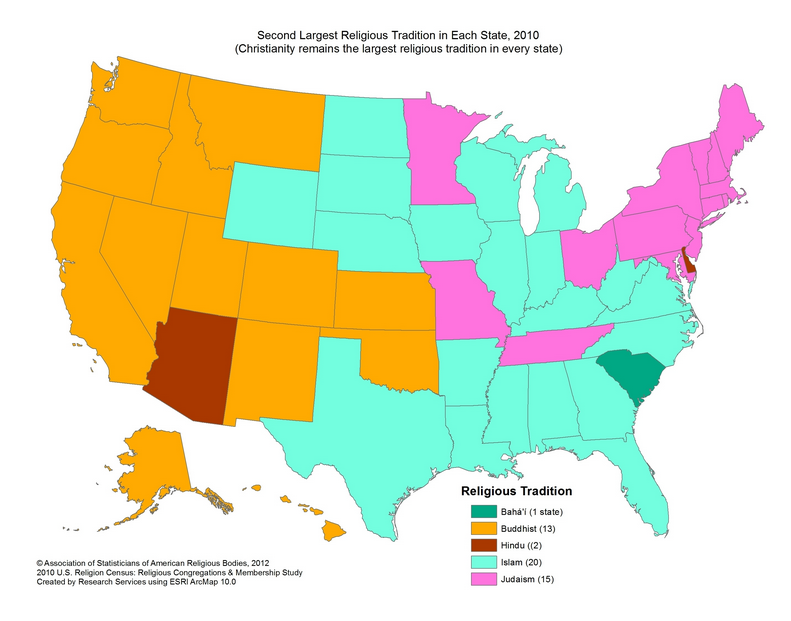

Consequential Maps

This recent map making the social media rounds depicts the runner-up religions for each U.S. state, based on data from the US Religious Census project. NPR, among others, has discussed the map, attempting to explain the anomalies in the map. Why is South Carolina’s second largest religion listed as Bahai and Tennessee’s Judaism when every other southeastern state is Islam? Why are Delaware and Arizona the only states with Hinduism as the second largest religion? Continue reading “Consequential Maps”

This recent map making the social media rounds depicts the runner-up religions for each U.S. state, based on data from the US Religious Census project. NPR, among others, has discussed the map, attempting to explain the anomalies in the map. Why is South Carolina’s second largest religion listed as Bahai and Tennessee’s Judaism when every other southeastern state is Islam? Why are Delaware and Arizona the only states with Hinduism as the second largest religion? Continue reading “Consequential Maps”

The Politics of Representation

During the ongoing campaign for India’s Parliament, a leader of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), Mayawati, reportedly asserted that Dalits are not Hindu. The BSP, whose name itself identifies those outside the upper castes as the majority of the population, receives its primary support from Dalit communities and advocates for policies that promote the interests of the disempowered, while the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that Mayawati was criticizing is generally connected with Hindutva movements commonly associated with upper castes. Continue reading “The Politics of Representation”

During the ongoing campaign for India’s Parliament, a leader of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), Mayawati, reportedly asserted that Dalits are not Hindu. The BSP, whose name itself identifies those outside the upper castes as the majority of the population, receives its primary support from Dalit communities and advocates for policies that promote the interests of the disempowered, while the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that Mayawati was criticizing is generally connected with Hindutva movements commonly associated with upper castes. Continue reading “The Politics of Representation”

Brand Loyalty

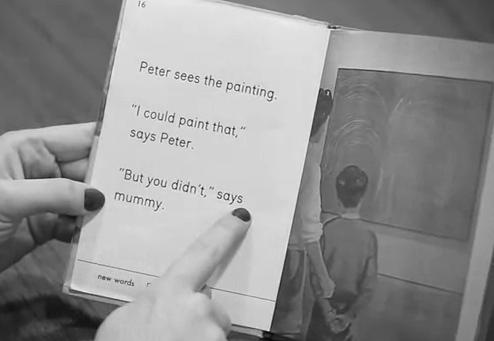

Have you heard of the parody of the 1960s “Peter and Jane” readers for kids, and how Penguin UK has threatened a lawsuit unless the author and small publisher “pulp” the books?

Have you heard of the parody of the 1960s “Peter and Jane” readers for kids, and how Penguin UK has threatened a lawsuit unless the author and small publisher “pulp” the books?

No? Then come up to speed with this article. Continue reading “Brand Loyalty”

What Came First, the Difference or the Similarity? Part 2

Yesterday, in Part 1, I wrote about some of the conceptual problems that I find in a recent Hufftington Post article on the ironic similarities between two sets of devotional rituals, said to be shared by Hindus and Buddhists in Sri Lanka, and the way — again, according to the article, and also the site on which it is based — that this commonality might provide a basis to overcome perceived difference and conflict.

Yesterday, in Part 1, I wrote about some of the conceptual problems that I find in a recent Hufftington Post article on the ironic similarities between two sets of devotional rituals, said to be shared by Hindus and Buddhists in Sri Lanka, and the way — again, according to the article, and also the site on which it is based — that this commonality might provide a basis to overcome perceived difference and conflict.

But there’s more to talk about at the site (created by, according to the Huff Post article, a Sri Lankan-based, University of Chicago trained anthropologist). For instance, its Intro page opens as follows: Continue reading “What Came First, the Difference or the Similarity? Part 2”

What is the Goal of the Academic Study of Religion?

Interested in some additional thoughts on the Doniger controversy? Then see our own Steven Ramey‘s new post at the blog for the Bulletin for the Study of Religion.

Interested in some additional thoughts on the Doniger controversy? Then see our own Steven Ramey‘s new post at the blog for the Bulletin for the Study of Religion.

[M]y intent is not to critique Doniger but to critique the tendency across the field to define religions in ways that give preference to one group over another, sometimes intentionally, sometimes unintentionally….

Arbitrary and Consequential

Recognizing the variety of calendars around the world, and thus the different occasions for marking a new year, illustrates the arbitrariness of time and our systems of marking time, which Russell McCutcheon has highlighted recently (here and here). In the context of South Asia, for example, many communities have new year commemorations at different times, primarily based on regional calendars. Continue reading “Arbitrary and Consequential”

Recognizing the variety of calendars around the world, and thus the different occasions for marking a new year, illustrates the arbitrariness of time and our systems of marking time, which Russell McCutcheon has highlighted recently (here and here). In the context of South Asia, for example, many communities have new year commemorations at different times, primarily based on regional calendars. Continue reading “Arbitrary and Consequential”

Bayart on Strategic Syncretism

“While British colonial administrators fabricated ‘Indianness’, Hindu intellectuals were formulating Hinduness by resorting to ‘strategic syncretism’. According to Christophe Jaffrelot, this involved ‘structuring one’s identity in opposition to the Other by assimilating the latter’s prestigious and efficacious cultural characteristics’: ‘The appearance of an exogenous threat awakened in the Hindu majority a feeling of vulnerability, and even an inferiority complex, that justified a reform of Hinduism borrowing from the aggressor its strong points, under the cover of a return to the sources of a prestigious Vedic Golden Age that was largely reinvented but whose “xenology” remained active’.*… In short, the reinterpretation of India’s ‘Hindu’ past by the nationalists and their instrumentalisation of ‘tradition’ for militant political purposes have for nearly a century sustained a political identity unprecedented in the cultural landscape of the sub-continent, by incorporating foreign representations into Hinduism — e.g., egalitarian individualism, proselytisation, ecclesiastical structures — and by seeking to ‘homogenise in order to create a nation, a society that is characterised by extreme differentiation’.** On the Indian political chessboard, the celebration of a golden Vedic age is a mere fig-leaf concealing modernity, like the versions of African ‘authenticity’ that developed in the wake of the colonial invention of tradition…” (37-38)

* Christophe Jaffrelot, Les Nationalistes hindous (Paris: Presses de la Foundation Nationale des Sciences Politiques, 1993, p. 24, 41).

** Ibid., 83-4.

[This is one of an ongoing series of posts, quoting from Bayart’s The Illusion of Cultural Identity, that further documents the theoretical basis

on which Culture on the Edge is working.]